On 10 November 1995, environmental and human rights activist Ken Saro-Wiwa and eight community leaders were executed by the Nigerian state. Ken Saro-Wiwa was leading a protest movement against the ecological disaster that oil production had caused in their homeland, Ogoniland. At the time, Amnesty International described their trial as “politically-motivated and grossly unfair”.

Twenty years later, communities in Ogoniland continue to suffer the consequences of Shell’s oil spills. Between July and September 2015, people in Ogoniland told Amnesty International how oil spills, and Shell’s failure to clean them up, devastated their farms, damaged their health and left them with bleak prospects for the future.

“Our crops are no longer productive. No fish in the water.”

Emadee Roberts Kpai, farmer from Kegbara Dere, Ogoniland

Emadee, 83 years old, saw oil spills devastate his lands:

“Things were much better before Shell arrived. Since Shell came to this area, things began to change for the worse in our communities. This is because back then, if you go down to the creeks to fish, there was no crude oil in the creeks, so you can get fish. If you plant crops, gas will not destroy anything you plant.

“When Shell came to our community, the town crier called and we assembled at the town square and Shell addressed us. They promised that if they find oil here they’ll transform our community and everybody will be happy. We were all happy. They came appealing to us to grant them permission for their exploration.

“Our crops are no longer productive. There are no more fish in the water. We plant the crops, they grow but the harvest is poor. We used to go fishing. We used to swim. We used to do all sorts of things in the river, because it was clean. Even our fruit trees were very productive. Before the pollution and contamination, children would go to the river and swim and play, but now no more. ”

“The oil came down and destroyed everything.”

Taagaalo Christina Dimkpa Nkoo, Barabeedom, Kegbara Dere, Ogoniland

Taagaalo, a 65-year-old farmer, told Amnesty International that she used to grow coconuts, yams, and cassava, but all her trees died after an oil spill in 2009 at the Bomu Manifold, where several Shell pipelines meet. The resulting fire burned for 36 hours. She says she still finds oil in the soil.

“The oil came down and destroyed everything…The oil doesn’t allow yams or anything to grow…We cannot live well anymore.”

“We have no hope for our children in this community.”

Barine Ateni, farmer from Kegbara Dere, Ogoniland

Barine is a 45-year-old farmer in Kegbara Dere. She is a widow with seven children between 15 and 30.

Her community was severely affected by oil spills from Shell’s Bomu Well 11 in Boobanabe, where Amnesty International researchers saw signs of oil pollution in 2015. Shell claims to have cleaned up the spill twice: in 1975 and 2012.

“When I was born, Shell was already in operation here in this community. Things have been going from bad to worse while growing up in this community. There have been oil spills all the time.

“Even shellfish are no longer there, or periwinkles or things like that. Women have to travel to faraway places to buy it before they use them.

“We, the women, say Shell should go. They should leave our community. They came here with death and destruction. We don’t want them here anymore.”

Barine explained the daily struggle the community faces coping with oil-polluted lands and water:

“Everywhere is coated with oil. Even the boreholes, the underground water is polluted. Sometimes we collect water from the boreholes and you see the surface littered with crude oil. So it’s not safe for us to drink.

“The children can no longer go to the river or stream to play like they used to do before. Because everywhere is coated with crude. The children can no longer swim, so they play here in the compound…We have no hope for our children in this community.

“We want Shell to compensate for all the damages they have done to this community, provide scholarships for our children, and provide medical facilities to deal with the health of our people in this community. We want the authorities to ask Shell to clean up this place … and ensure that our community is restored back to normal for our children.”

“We want Shell to remedy our environment so it could be of use to us once more.”

Boldesi Nuta, farmer from Kegbara Dere, Ogoniland, Niger Delta

Boldesi is a 48-year-old farmer. She has lived in Kegbare Dere her whole life and her children go to school there. She told Amnesty International that when she was 18 years old her foot was badly wounded when a Shell pipe, which had been lying unprotected in the open, exploded. She spent four months in hospital, several days in a coma. The resulting oil spill devastated her family’s cassava farm.

She told Amnesty International about the long-term damage the explosion caused her, and her community:

“Since that incident, I have never passed along that route. I know the area is now contaminated. No more farming in that area. The entire place is polluted. I have never been to the farm. Nobody else has been to that farm.

“Sometimes my children ask me how can they live, how can they face the bleak future that’s ahead of them. They ask me questions that I am unable to answer. They ask me a barrage of questions about their future which are difficult for me to answer. They see a bleak future.

“We want Shell to remedy our environment so it could be of use to us once more…In our farms, when we plant, we plant in polluted soil and the crops we harvest are also polluted. So the food we eat is contaminated. The air we breathe is polluted.”

“Ken Saro-Wiwa’s activism played a significant role in my life.”

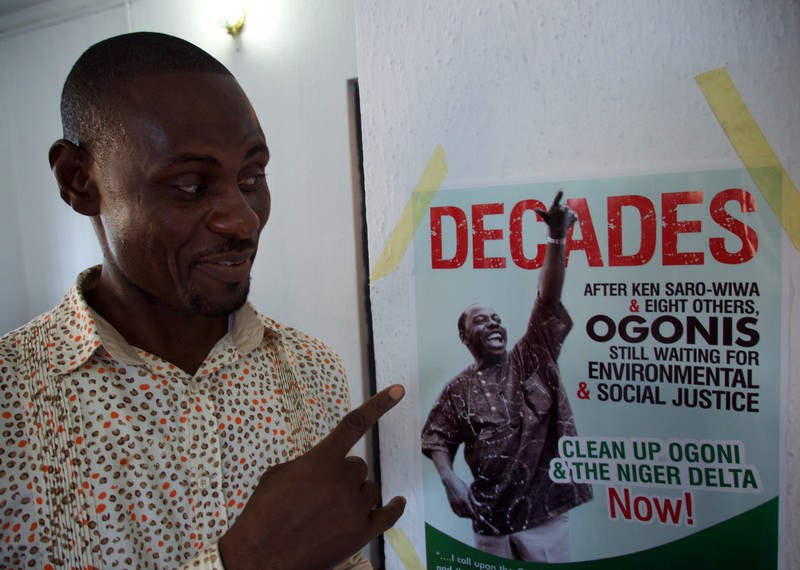

Fyneface Dumnamene Fyneface, Human Rights and Environmental Activist, Port Harcourt

Activist Fyneface has been at the forefront of campaigns for the rights of the Ogoni and Niger Delta people, first as President of the National Union of Ogoni Students, Port Harcourt chapter, and for a Nigerian NGO called Social Action.

He told Amnesty International how conditions in the Niger Delta and the legacy of Ken Saro-Wiwa inspired him to become an activist:

“When you get to a polluted environment, you’ll see that the people’s livelihoods have been destroyed. They don’t have good water to drink. Sea food has been destroyed. Their cassava and other things they plant on the farms are no longer doing well. So lives in those environments are no longer bearable.

“Ken Saro-Wiwa’s activism played a significant role in my life. It affected me a great deal by inspiring me so much to work for the Ogoni people. Because when I was growing up as a child, I heard about Ken Saro-Wiwa. I saw him once speaking to the people of Eleme in 1992, three years before he was killed. At the time, I never really knew what the man was talking about, but now I’ve grown up to see what he was talking about. And I’m ready to continue from where Ken Saro-Wiwa stopped by pursuing to ensure that the people have justice for the environment.

“It’s very significant to note that it’s now two decades since Saro-Wiwa was killed with his kinsmen, over the struggle for the environment that is our right…and justice has still not been done.…Twenty years; nothing has been done. Twenty years; Ogoniland is still polluted. Twenty years; no clean-up has been done. Twenty years; justice has not been achieved. Twenty years gone by and what they fought for have not been addressed. That cannot continue.

“This 20th anniversary should be used to re-echo the voice of the people of the Niger Delta. To re-echo the voice of the ethnic minorities. To re-echo the voice of the Ogoni people so that the struggle can be sustained.”