Cali, the ‘branch of heaven’ as it was baptised in a popular salsa song in the eighties, has reached the end of one month of hell. What began with a day of national strike to reject a tax reform led to a social outburst unprecedented in the recent history of this city, the most important in the southwest of Colombia. The blockades in some of its main roads, as well as in the accesses and exits, the incinerated vehicles, the sticks and stones that cover its streets, illustrate the chaos. But that turns out to be the least of it if compared to the number of dead, wounded and missing people that accumulate as the days go by, as a result of the confrontations between demonstrators and the police, between the poor and the rich citizens, between nonconformists and anonymous armed people, in a city in fear and on the defensive.

The uncertainty caused by such a panorama calls for decisive action to address the serious human rights violations, to stop the violence and to seek solutions to structural problems that with this protest have torn the seams of a fragile patchwork quilt: that of the social fabric of this region, very similar to other places in Colombia today.

There are countless causes. “This is a passionate city,” Diana Solano, professor at ICESI University, the most prestigious of all the local private institutions, told CONNECTAS. This is shown in the history of the 485-year-old city, the city in Latin America with the second largest Afro-descendant population, according to the Secretariat of Economic Development, after Salvador de Bahía, in Brazil; with a significant Indigenous presence as the largest city in the south of the country – a region neighbouring Ecuador – and rich cultural expressions in a city of almost two and a half million inhabitants. This places it third in population after Bogotá and Medellín, and at the same level in terms of commercial importance. But the potential of this diversity has been curtailed by historical racism and classism. Exclusion is so common that it has become just one more element of the green landscape of the valley populated by saman trees, bordered to the west by the Farallones de Cali mountains and bathed by seven rivers.

It is a city surrounded by a thriving sugarcane agroindustry produced in vast estates, which in recent years has faced a great challenge due to the permanent arrival of hundreds of thousands of dispossessed and persecuted people. Some of them, originally from the Pacific Coast, most of them Afro-descendant people, have been hit by the triple war between the State, armed actors and drug trafficking. Others, members of Indigenous communities in the neighbouring department of Cauca and in the south of the country, are fighting for the rights to their worldview and remain firm in their ancestral claims. All of them, excluded from the southwest of Colombia, have been arriving for decades to settle outside the city in areas with their own names: Aguablanca District to the east, Siloé to the south and Terrón Colorado to the west, three points where the evils from which they sought to escape are replicated, and which today are the strongest points of social explosion and protest. A social patchwork to which thousands of Venezuelan families who left their country because of the crisis and settled in these same places of need, and in many cases of misery, are added.

In this social powder keg, 27.2 percent of the nearly 600,000 young people living there were unemployed in the first quarter of 2021, according to the National Statistics Department (DANE), while another 67.9 percent survive in conditions of economic informality. In addition, according to the report ‘Cali, cómo vamos’, 65 out of every 100 young people live in the most impoverished strata, numbers 1 and 2 in Colombia’s economic stratification system that goes up to stratum 6. To top it all off, violence is part of everyday life. Before the protests, the murder rate averaged 50 per 100,000 inhabitants, one of the highest in Latin America, and according to a 2019 United Nations report, there are 183 criminal groups or organisations in Cali.

It is these same young people, impoverished and exposed to criminality, who are the protagonists of the current protest. They are also the main victims. Although there are no consolidated figures, most of the victims of street clashes correspond to this population group. While the Attorney General’s Office says that the number of violent deaths directly related to the demonstrations at the national level is close to twenty, the joint figures of recognised civil society organisations such as Indepaz and Temblores assure that in Cali alone the figure is close to thirty. Of these, 21 killings were allegedly committed by the security forces.

On 28 May alone, the day marking the first month of protests, according to what the Secretary of Security of Cali confirmed to Caracol Radio, there were 10 deaths during the day of protests. One of them was in fact an official of the Attorney General’s Office who was beaten and stabbed to death in a lynching by an enraged crowd after he shot and killed two young men when they blocked his way at one of the assembly points. The highest investigative body came out and assured that the official who was lynched was on his day off. This happened in the sector of La Luna, where days before a fire was set in a hotel where policemen were staying, a dramatic event similar to the one that took place in Bogotá around the same time where a dozen policemen were almost burned to death, cornered by attacks in a small police station.

The growing violence, added to images going viral online of people in civilian clothing shooting next to police officers not exercising any authority, unleashed violent havoc in the city, which led the city government to impose a strict curfew from seven o’clock at night. In response to the outcry from the local authorities due to the growing lawlessness, the national government announced the dispatch of 7,000 members of the army and the navy to retake control of the roads and highways in Cali and Valle del Cauca.

The more than 20 focal points of the protest in the city have been at the same time epicentres of peaceful mobilisation, blockades and confrontation. They are the daily space where the ‘pelados’, (skint or broke young people) as they have sought to characterise the young people of these sectors, roam. Several of them make up what has been called ‘the front line’, those equipped with armour ready to revolt and confront. It is a scattered strike force, where some have not only found a sudden reason for being or a sense of belonging, but also a means of subsistence, because being there they have the food that is scarce in their homes, provided by sympathisers from the same neighbourhoods.

Although the ‘front line’ has been the most visible face of this protest, there is a melee of actors and claims that are mixed in the mobilisation, and a significant peaceful but firm participation of young people and organisations that have been denouncing neglect and inequality for years. In this region of Colombia, this revolt could be called ‘bochinche’, (ruckus) which is precisely the name that John Eyder Viáfara and a group of young people decided to give to their collective, an organisation that was born seven years ago with the purpose of preventing their contemporaries, residents of the poorest areas, from ending up feeding the city’s crime rates. To achieve this, they have put their necks on the line by crossing the invisible borders imposed by gangs in their neighbourhoods.

They have also been committed to combating cycles of poverty with their ongoing campaigns to deliver condoms to prevent teenage pregnancy, and to strengthen the potential of diversity through art. But perhaps one of the most outstanding results is their role in the formation of leaders in a society without much leadership. John Eyder estimates that the number of young people with whom they have made contact is around five thousand. But beyond the numbers, what excites him most are the ‘small victories’: “If you can convince a young guy not to join an ‘oficina de cobro’ (criminal structures dedicated to hired killings and extortion, among other practices) and instead work hard, you are already saving the world,” he said in an interview with CONNECTAS.

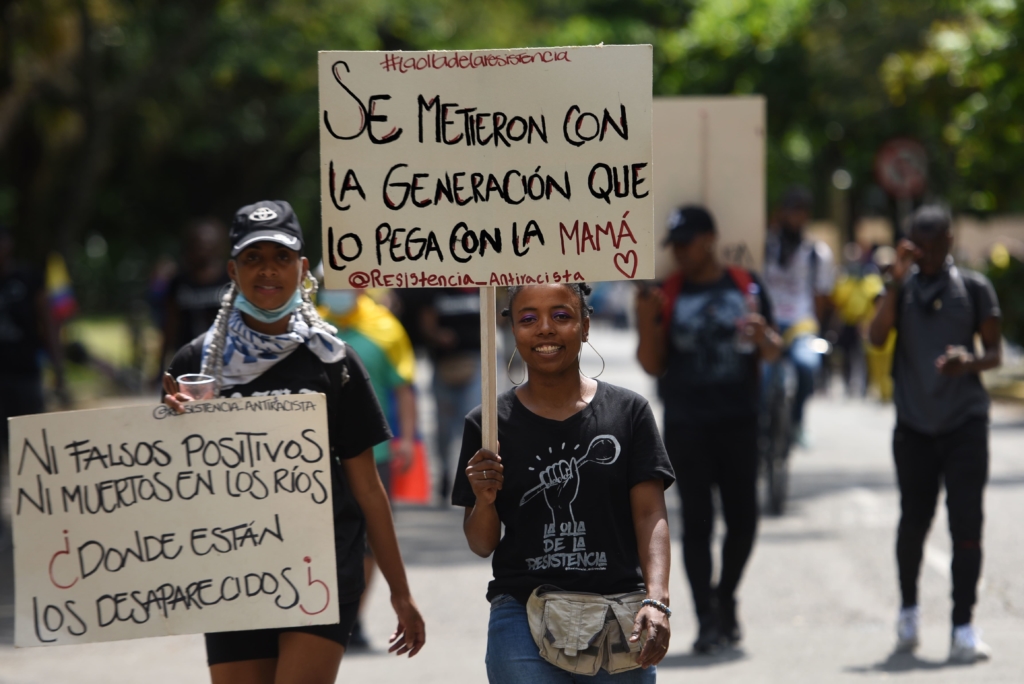

Since the national strike began on 28 April, there have been at least 20 assembly points where mobilisations and blockades of automobile and sometimes pedestrian traffic have been a constant. As the days have gone by, many things have begun to change there. One of them was the name of the sites, which became known as ‘resistance points’. Thus, a popular eatery known as ‘Puerto Rellena’, which is the name of a traditional sausage, became ‘Puerto Resistencia’. The bridge of the Thousand Days is now ‘Bridge of the Thousand Struggles’ and La Loma de la Cruz (the Hill of the Cross) became Loma de la Dignidad (the Hill of Dignity).

Young people from the poorest sectors of Cali, each in their own way, tell stories in which their humble origins, inequality and lack of opportunities form a triangle that, in turn, leads to a similar figure as an answer: poorly paid odd jobs, criminal gangs or enlisting in the Police, for which they have to pay.

Those who manage to escape this fate speak of it with pride and rather quietly. Yonny arrived in Siloé when he was 16 years old, at the end of the nineties. With the encouragement of his family, he joined an artistic project. After a while, he did an accelerated secondary school certificate course because he was not accepted at school and then found a place to specialise in popular education at the Universidad del Valle, the main public university in the city. He recalls that, in order to take the medical exams for entrance into university, his mother pawned the sound system from their house. He often had to walk an hour and a half from home and back because he did not have enough money for transportation. He rarely went out to party in a city where it is a part of life. “I hope to make up for it from the age of 50 onwards, to be a partying old man,” he says.

He is now studying law while pursuing a master’s degree with a scholarship granted to Pacific leaders by the University of the Andes, the most prestigious of all the private universities located in Bogotá. And through Fundación Créalo he helps young people who, like him, yearn to access higher education or develop a productive project.

For Yonny, there are two different groups of young people linked to the protest in Cali. “Those on the front line, who risk their lives, because they have nothing to lose. They are not afraid. If the state doesn’t kill you, you’re going to be killed here in the communes by hunger or in the internal conflict between gangs.” Others are young middle-class university students who demand better living conditions and dream of a better country. “Colombia lacks opportunities, and even for the privileged ones who have studied, job options are scarce and bad,” he says.

This precarious situation is not exclusive to young people in Cali but is replicated nationwide. The population of young people between the ages of 18 and 28 who neither study nor work, who in other countries have been characterised as ‘NiNis’, went from 19 percent in Colombia in mid-2019 to 33 percent in mid-2020. Iván Daniel Jaramillo, researcher of the Employment Observatory of the Universidad del Rosario, told the La Silla Vacía site that the presence of ‘NiNis’ increased exponentially in the current protest compared to November 2019, the prelude to the current social outbreak, interrupted by the pandemic. “Those participating to demand employment opportunities and education is clearer, and discontent is much greater.”

But even those who work or study have come out to protest or support the mobilisation. According to a survey conducted by the Universidad del Rosario, the capital newspaper El Tiempo and the pollster Cifras y Conceptos, 84 percent of the young people surveyed, aged between 18 and 32, feel represented by the national strike. The majority, according to this survey, reject the current government and the violence exercised by the security forces.

Diana Solano believes that there are characteristics of this generation of young people that explain the strength of the current social outburst. “The youth of today are more authentic, less repressed. This has a lot to do with the affective politics of containment, the prominence of the idea that you have to put up with life as it is has decreased”. In addition, she points out that their way of relating to authority figures has changed, as they are much more horizontal, less hierarchical and more demanding.

Carlos Peña, a 24-year-old lawyer, is one of the young people mobilising in Puerto Resistencia, a point that marked a before and after in this protest, since it was there that one of the first victims of the confrontation with the security forces fell. On 28 April, 17-year-old Marcelo Agredo kicked a policeman, to which the officer responded by firing two shots, one of which killed him. Everything was recorded on video, and this is one of the four cases in which the Attorney General’s Office has already acted. After this murder, ‘the front line’ expelled the police and Puerto Resistencia became a kind of autonomous space, a public square, as Carlos Peña shared for this report, organised by the NiNis, with the support and solidarity of the people of the area.

For this young man who has been involved in activism and political pedagogy for five years now, what this outburst shows is the failure of representative democracy. “People have now understood that democracy is implemented mainly in the streets and not only and exclusively every four years when one goes to exercise the right to vote. Young people are no longer waiting for someone to solve the problem for them”.

How can this outcry from young people be turned into real changes and growth within society? There have been some initiatives in the education sector. Colombia’s education system under the previous government of Juan Manuel Santos created programmes in recent years such as ‘Ser Pilo Paga’, to facilitate the entrance of low-income students with outstanding academic grades to higher education centres, some of them elite. Thus, there are those who, coming from the low-income sectors of eastern Cali, share classrooms with residents of the exclusive sector of Ciudad Jardín, one of the most affluent areas of the city.

Several teachers agree that it is common for them to show deficiencies in reading comprehension, writing, English language skills and technological tools. They warn that, although they often manage to catch up, these young people are caught between their most basic needs and the obligation to maintain grades that allow them to keep their places.

This is precisely one of the main complaints of the young people in this protest, as John Eyder points out: “When we ask for quality education, we are talking about an education that gives us tools to live, and to live well. Not having to start everything in life always further behind. In education, further behind; in work, further behind. And then they come and tell us that people are poor because they want to be.”

The situation is no different in the rest of the Colombian Pacific region. Óscar Gamboa Zúñiga, director of the National Association of Mayors of Municipalities with Afro-descendant Populations, Amunafro, explained for this report that “a reinvention of education towards an infrastructure of opportunities” is necessary. For him, the problem lies not only in access to education, but also in supply. “In Buenaventura, despite being the main port in Colombia (two hours from Cali), there is no career related to port issues. Just as there are no water-related careers in Chocó (the neighbouring department to the north and one of the poorest in the country), despite being one of the places with the most water resources on the planet. Therefore education is not a precursor to development if we take into account the resources we have”.

After several days of trying to dismiss the protest, focusing on the acts of vandalism that occurred alongside the peaceful mobilisation, the government seemed to understand the importance of youth participation and their complaints about access to education. Therefore, 15 days after the beginning of the national strike, President Iván Duque announced from Cali free tuition fees for the second semester of 2021 for all students of strata 1, 2 and 3 in public higher education institutions. A measure that was seen as a good gesture, but insufficient to solve the structural problems of the system, as well as to extinguish the fire of the protest.

DANE figures show that it was in Cali’s poor neighbourhoods where unemployment increased the most from 2019 to 2020, above 20 percent. Translated into pesos, the real income of this population was reduced by half. As a result, nearly one million people fell into monetary poverty in the first year of the pandemic, many of them forced to subsist on less than 356,962 pesos per month, the equivalent of 100 US dollars.

This social bomb has greatly affected the Afro-Colombian population, as reported by Erlendy Cuero, member of the National Association of Displaced Afro-Colombians, Afrodes, “and it exploded now with the national strike”. Erlendy Cuero told CONNECTAS that this situation is not new and that, in reflecting on the situation of her community, and especially of young people, there is an event that reflects it in its entirety: the massacre in August 2020 of five teenagers in Llano Verde, a poor neighbourhood in the east of the city, barely ten years old and where displaced and reintegrated people, mostly Afro-descendant people, live together.

In that incident, the minors, between 14 and 16 years of age, were killed by gunshots to the head while they were in a cane field flying kites and eating sugar cane. Although there were arrests made, the general feeling is that the reason for these murders has not been fully unravelled. “I told Mayor Jorge Ivan Ospina: here in the east of Cali we are not being killed by COVID, for us violence is more lethal,” complains Cuero, and she accuses the official of dismantling the programmes of his predecessor, Maurice Armitage, in which young people were employed, among other things, as tour guides and were paid a fee. “At least one person in each family was guaranteed food.” Ospina’s Social Welfare Secretariat was consulted but did not confirm this information.

Armitage, a businessman and mayor in the period 2016 – 2019, believes that the authorities lack humanity and knowledge of the street, and that “the elite have become used to seeing the ones from below always screwed. And we accept that, we are not moved by poverty or the anguish of others,” he said in an interview with the BBC.

But the problem is even bigger than that. According to Professor Fernando Urrea, quoted by the capital newspaper El Espectador, “any budget of any secretariat in Cali in the last decades is much lower than those of capitals such as Medellin and Bogota. This has to do with a policy of the elites to neglect investment in the supply of goods and services,” he says.

Abundance and misery are two sides of the same city, which face each other in some places like Portada al Mar, where neighbourhoods with luxury houses in strata six are only streets away from Terrón Colorado, Vista Hermosa, Patio Bonito and Aguacatal, in strata 1 and 2. Jefferson Lozano, one of the young people protesting at this point, told us that in the first days of the demonstration and blockades people shot at them, threw ice and excrement at them. “And there are still those who want to fire bullets at us,” he says. But then they began to engage in dialogue. “They have told us that this whole issue has stirred their conscience, because they confess that they had focused on making money without thinking about anyone else. These are not radical changes, but it’s at least a start.”

Jefferson claims he has been threatened. “If they kill me for defending the people, I died defending what I believe is right,” he says. “And if someone has to use bullets to defeat you, it’s because they had no argument.” A violence that anyone can be exposed to. This is the case of Nicolás Guerrero, 22 years old, a young artist who died of a gunshot to the head while he was at a ‘velatón’, a candlelit vigil in tribute to the victims killed during the demonstrations. This crime caused shock due to the announcement made by the mayor of the city, Jorge Iván Ospina, in which he condemned the crime while confirming that he was his relative, the son of one of his cousins.

The violence has escalated and been replicated throughout the department of Valle del Cauca, of which Cali is the capital, and has deteriorated to the point of disrespecting humanitarian work. On 22 May a baby died in an ambulance that was trapped in one of the blockades between Buenaventura and Cali. Two days later, Armando Alvarez, an official of the health network in the east of Cali, known for having assisted those wounded in the confrontations in Puerto Resistencia, was killed; a macabre confirmation of the report published shortly before by the renowned journalist Alfredo Molano Jimeno, according to whom a price was being put on the lives of those who provide medical assistance in the protests.

In spite of everything, the cry of the young people of ‘the branch of heaven’ seems to have been heard and has managed to go from a ‘bochinche’ to an articulated petition. “After changing spaces and, above all, attitude and internal dialogue, the Cali Resistance Union, with spokespeople from its 25 points, managed to meet with the local, departmental and national government, for a respectful dialogue, proposals and answers,” said the Archbishop of Cali, Dario Monsalve, on his Twitter account. And an inter-partisan commission of the House of Representatives has worked for two weekends in the city to discuss with young people like Jefferson, Carlos and John Eyder the urgent reform to the police, besides exploring employment options together with businesspeople.

As in Cali, young people in different cities of Colombia continue to take to the streets, at the cost of their own safety, in the midst of recurrent scuffles with security forces and the rejection of a part of the population that has also come out to demonstrate to demand an end to the blockades. “We have already lost everything, even fear”, read the banners of the youngest. While there is no end in sight to the complex situation, they and the rest of a country that is still trying to decipher the keys to this outbreak are only sure that Colombia will never be the same as it was before the strike, and that many things will have to change.

*From the CONNECTAS Editorial Team, lead reporter María Camila Hernández and jointly produced with Víctor Diusabá, Mauricio Builes and Carlos Eduardo Huertas. Images: Amnesty International archive/Christian Escobar Mora