Around 1am on 17 January 2022, Myanmar military fighter jets dropped two bombs on Ree Khee Bu camp for displaced persons in Kayah State. The attack killed Nu Nu, a man in his 50s, as well as Maria and Caroline, sisters who were around 15 and 12 years old.

The camp was a refuge for people fleeing violence, but even there, civilians could not escape the Myanmar military and its deadly air campaign.

For the first time since the military coup of February 2021, Amnesty International, in collaboration with Justice For Myanmar, presents a detailed account of one of the most secretive business operations in Myanmar – the supply of aviation fuel to the military.

After the military coup in 2021 and the brutal crackdown on protestors, fighting between the Myanmar military and armed groups across the country escalated significantly.

Increasingly the Myanmar military relies on its air force, which regularly carries out air strikes with fighter jets and attack helicopters.

The impact on civilians is often devastating.

Every time I hear the planes flying over our village, I feel unsafe and afraid…

Witness

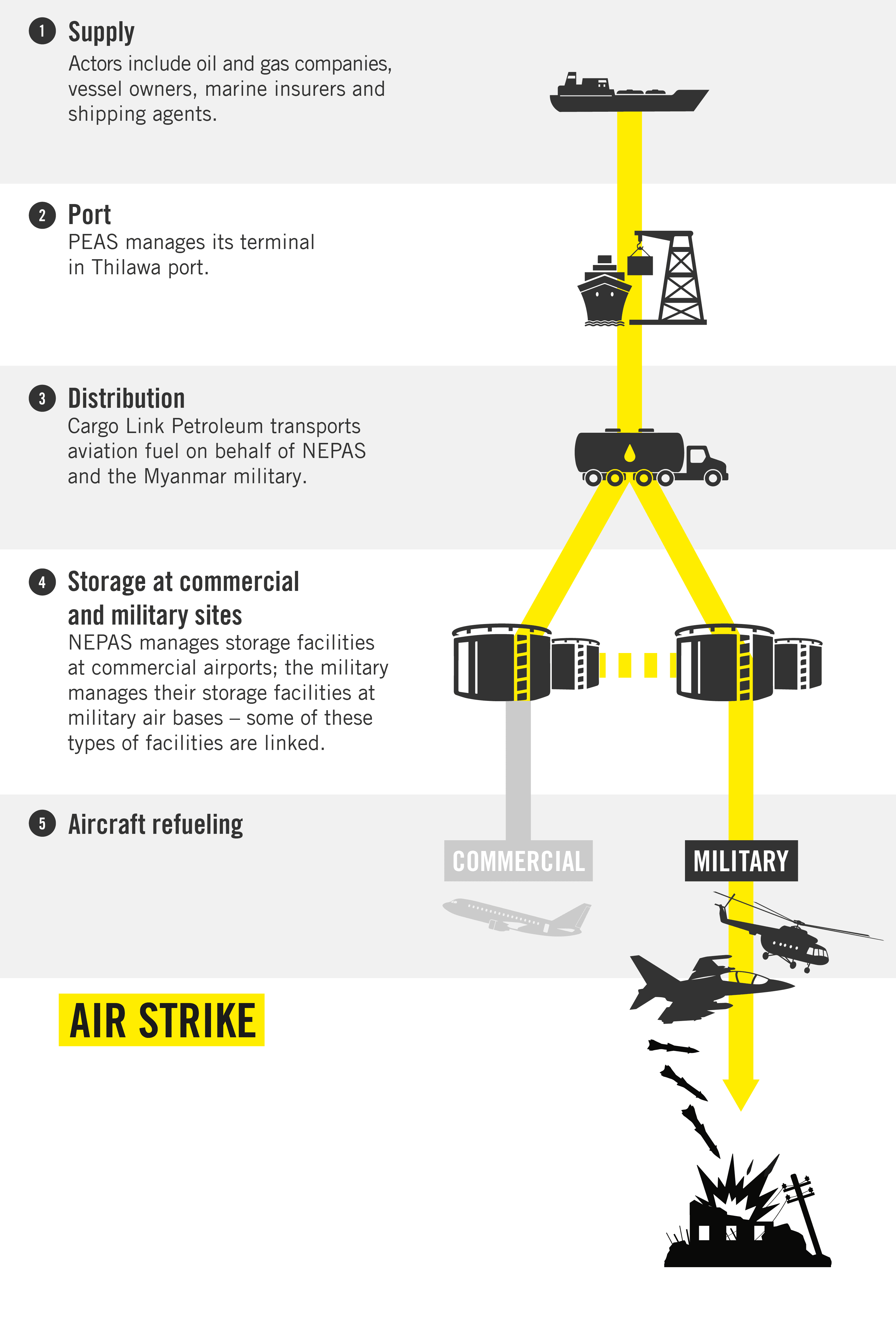

The Myanmar military relies on aviation fuel that is supplied, imported, handled, stored and distributed by a number of companies, both foreign and domestic.

Amnesty International’s newest report provides a detailed account of this supply chain – from the port where the fuel originally departs to air strikes conducted by the Myanmar air force that amount to war crimes.

Read THE FULL REPORT

The corporate supply chain bringing Jet-A1 to Myanmar

Since 2015, the main foreign business actor involved in the supply chain of aviation fuel has been Puma Energy – a global energy company incorporated in Singapore that is based in large part out of Geneva, Switzerland, and beneficially owned by global commodity giant Trafigura.

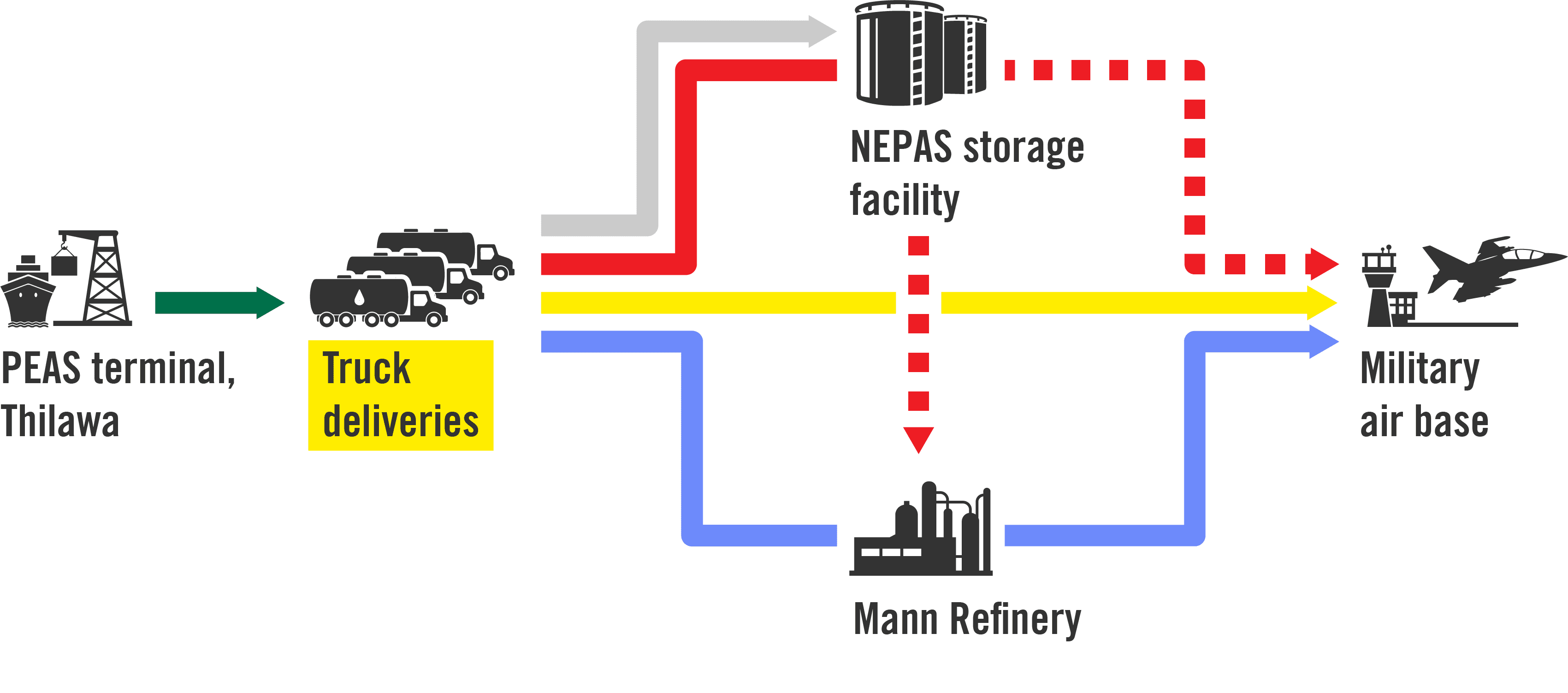

This report shows how Puma Energy’s two Myanmar affiliates – fully owned Puma Energy Asia Sun (PEAS) and joint venture National Energy Puma Aviation Services (NEPAS) – played a role in supplying aviation fuel to the Myanmar military. PEAS is responsible for handling and storing aviation fuel delivered to Thilawa port terminal, Yangon, and NEPAS for procuring, selling, distributing aviation fuel as well as providing refuelling services at 11 Myanmar airports.

Puma Energy announced on 5 October 2022 that it was selling its assets in Myanmar and exiting the country. It also communicated to Amnesty International that since the February 2021 military coup, it “has not supplied, sold or distributed any fuel or products to the Myanmar Air Force.” However, Puma Energy also explained that it decided to leave Myanmar in part because it had received reports “of incidents where the MAF [Myanmar Air Force] had been able to breach controls that were put in place to maintain the segregation of civilian supply.” Puma Energy has not provided a date of its planned departure and as of 3 November 2022, the company explained that it continues to own PEAS and have a minority stake in NEPAS.

Corporate supply chain

Suppliers transport Jet A-1 by sea

Amnesty International found the Myanmar military uses Jet A-1, a type of aviation fuel that is also used by the majority of commercial aircraft.

PEAS terminal at Thilawa port receives and stores Jet A-1

The majority of Jet A-1 fuel enters Myanmar through a terminal operated by PEAS at Thilawa port.

Between February 2021 and 17 September 2022, at least seven oil tankers offloaded eight shipments of Jet A-1 at the PEAS terminal in Thilawa port for a combined import volume of 66,626 metric tons (MT) in 2021 and 31,577 MT in 2022.

Amnesty International confirmed the supplier of four of the eight shipments: PetroChina’s wholly-owned Singapore Petroleum Company (December 2021), Rosneft (December 2021), Chevron (February 2022) and Thai Oil (June 2022). In addition, vessel tracking data links ExxonMobil to a shipment of aviation fuel that departed from its refinery in Singapore and arrived in Myanmar in June 2022.

Chevron, Rosneft and Thai Oil explained to Amnesty International that their shipments were meant to be used for civilian purposes only. However, Amnesty International obtained leaked documents showing how the shipments supplied by Singapore Petroleum Company and Thai Oil were delivered directly to the Myanmar military on arrival at the port.

After Amnesty International shared these findings with Thai Oil, the company responded stating that in order “to avoid any doubt about the compliance of good corporate governance policy, our business unit has decided to hold a selling of Jet A-1 to Myanmar until no such concerned issue.” Singapore Petroleum Company did not respond to Amnesty International’s multiple letters.

Trucks distribute Jet A-1 across Myanmar

On arrival, the aviation fuel is stored at fuel tanks in the PEAS terminal. From there, Jet A-1 is loaded onto tanker trucks, which transport it across the country.

According to Amnesty International’s research, the main distributor of NEPAS’ Jet A-1 is a transport contractor known as Cargo Link Petroleum Logistics. The Asia Sun Group, a medium-sized Myanmar business conglomerate that owns various companies, including Cargo Link Petroleum – did not respond to Amnesty International’s letters.

Truck deliveries

Amnesty International obtained records that detail how trucks of Cargo Link Petroleum transport aviation fuel to NEPAS storage facilities at commercial airports and separately to airbases on behalf of the Myanmar military.

Significantly, there is a direct link between certain NEPAS storage facilities to which fuel was delivered and military airbases, a few of which Amnesty International has linked to war crimes. Click on the map below to see these connections.

At military bases, Jet A-1 is loaded onto aircraft

The military uses different airbases depending on the particular state or region that it is surveilling or attacking. In order to power the aircraft involved in such operations, it relies on aviation fuel delivered to its airbases.

Amnesty International has identified at least five airbases from where military aircraft involved in attacks departed between March 2021 and August 2022:

Jet A-1 fuels a deadly air campaign

On 5 February 2022, ground spotters reported two YAK-130 jets taking off from Hwambi Airbase at 12:46am heading to Hpapun District.

Shortly after 1am, two aircraft attacked houses in Ta Dwee Koh village, in Hpapun District. A 38 year-old farmer awoke to the sound of aircraft.

Shortly after, the shockwave from the blast threw one of his two daughters away from him and caused a serious injury to his 23-year-old wife’s lower spine. Two of his extended family members were killed in the house next door.

The man told Amnesty International that military aircraft had been flying over the area for some time, adding, “We thought that they won’t launch an air strike as they have no enemy in our village… I don’t know [why they struck us]… I don’t understand why they cause trouble to civilians.”

Amnesty International documented 16 unlawful air attacks that took place between March 2021 and August 2022 in Kayah, Kayin and Chin States as well as Sagaing Region. The attacks collectively killed at least 15 civilians and injured at least 36 other civilians. They also destroyed homes, religious buildings, schools, medical facilities and a camp for displaced persons.

Deadly cluster munitions used against civilians

In the course of this research, Amnesty International has documented multiple occasions where the Myanmar air force has employed cluster munitions.

In Chin State’s Chat village, in Mindat Township, community leaders, residents, and members of a local People’s Defence Force (PDF) held a meeting on 2 July 2022 in the village’s only school to discuss several issues, including education and development projects as well as security. Dozens of civilians packed a hall in the school’s compound; on a day off from school, many children were in attendance with family members or were playing in the vicinity. Close to 11am, people inside and outside the hall heard the sound of a fighter jet.

According to witness testimonies, there were multiple bombing runs that likely involved more than one fighter jet. The school hall where the meeting was held and the teachers’ dormitory next to it were destroyed, and classrooms sustained significant damage; at least four houses were also destroyed, two of them completely. Around 13 civilians were injured in the attack; roughly half of the village’s few hundred residents have abandoned their homes. Three PDF members who were inside the hall were killed.

Among the weapons used in Mindat Township were cluster munitions, which are widely banned because they are inherently indiscriminate. This attack constitutes a war crime.

Civilians attacked in schools and places of worship

Myanmar military air strikes have also destroyed civilian objects that have specific protections under international humanitarian law, including religious buildings and schools.

Attacks on medical facilities

Amnesty International documented three air attacks on medical facilities. International humanitarian law affords special protection to specific persons and objects, including medical personnel and medical units. Facilities and personnel used solely for the purpose of providing medical care should be protected from attacks in all circumstances.

On 9 August 2022, around 10am, a fighter jet fired on a health centre in Daw Par Pa village, Kayah State. Twelve people were inside, including medical professionals.

Jets passed over the medical facility multiple times, firing machine guns and at least one 80mm S-8KOM rocket.

I was standing beside the doctor as he was examining an asthma patient… As we were caring for the patient, one man said, 'I hear the sound of shooting.' The man stepped outside and then I heard the bombing…

Witness

The health centre, the only medical facility with a doctor in the area, had been operational for one month before the attack. There was no fighting in the area and no armed group base in the vicinity. This attack on the Daw Par Pa clinic amounts to a war crime.

Conclusion

In the vast majority of cases documented by Amnesty International, only civilians appear to have been present at the location of the strike at the time of the attack. In a few instances where armed group fighters were at the scene or nearby, the military’s indiscriminate use of large unguided bombs and inherently inaccurate rockets in populated civilian areas still constitutes a violation of international humanitarian law and, when civilians were killed or injured as a result, a war crime.

Such strikes have caused massive disruptions to people’s lives, including affecting their ability to farm their lands and to move around; they have also sparked widespread fear and resulted in mass displacement, at times of entire villages.

The unlawful air strikes have occurred together with the relentless shelling of villages with artillery and mortars, at times deliberately and at times indiscriminately; the use of internationally banned anti-personnel landmines that have killed and injured civilians; extrajudicial executions; torture and other ill-treatment; arbitrary detention; the burning of villages; and pillage, among other crimes.

Without the provision of aviation fuel, the Myanmar military would have no means to power the aircraft responsible for such air attacks. And yet companies continue to be part of this deadly supply chain, one that links international and domestic companies to the Myanmar military, which has been implicated by Amnesty International, the United Nations, and others in war crimes, crimes against humanity and other serious human rights violations.

Sign now – Ask companies and governments across the globe to help end the bloody oppression by the military in Myanmar

Since Myanmar military's coup on 1 February 2021, over 2,400 people have been killed there, including by unlawful air strikes.

Without aviation fuel, the Myanmar military would not be able to conduct its air attacks. We have uncovered disturbing evidence that several companies have been part of the supply chain that allows fuel to enter the country, despite the risks of that fuel being used to carry out deadly air strikes.

These businesses have a responsibility to assess the adverse human rights impact of their operations and partnerships. This means ending all involvement in the supply of aviation fuel to the Myanmar military, which is responsible for air strikes that amount to war crimes.

States also have a duty to protect against human rights abuses everywhere. That's why we're also calling on governments to act now and suspend the supply of aviation fuel to Myanmar.