Mali has witnessed increased war crimes and violence against civilians since 2018, particularly in the central regions of the country (Mopti and Segou). Despite commitments and investigations, justice has been slow in coming for the victims and/or their families and impunity still prevails, writes Amnesty International in a new report published on 13 April 2021.

Amnesty International’s 64-page report, Mali. Crimes without Convictions: An Analysis of the Judicial Response to Crimes in Central Mali, reviews the state of investigations into several crimes committed in central Mali since 2018 and identifies various institutional and legal barriers that are contributing to a denial of justice and truth for the victims.

Despite repeated commitments on the part of the Malian authorities, a number of judicial investigations –such as those into the Ogossagou and Sobane Da killings– have made little to no progress and the victims are continuing to demand justice while fearing reprisals in the absence of protection measures.

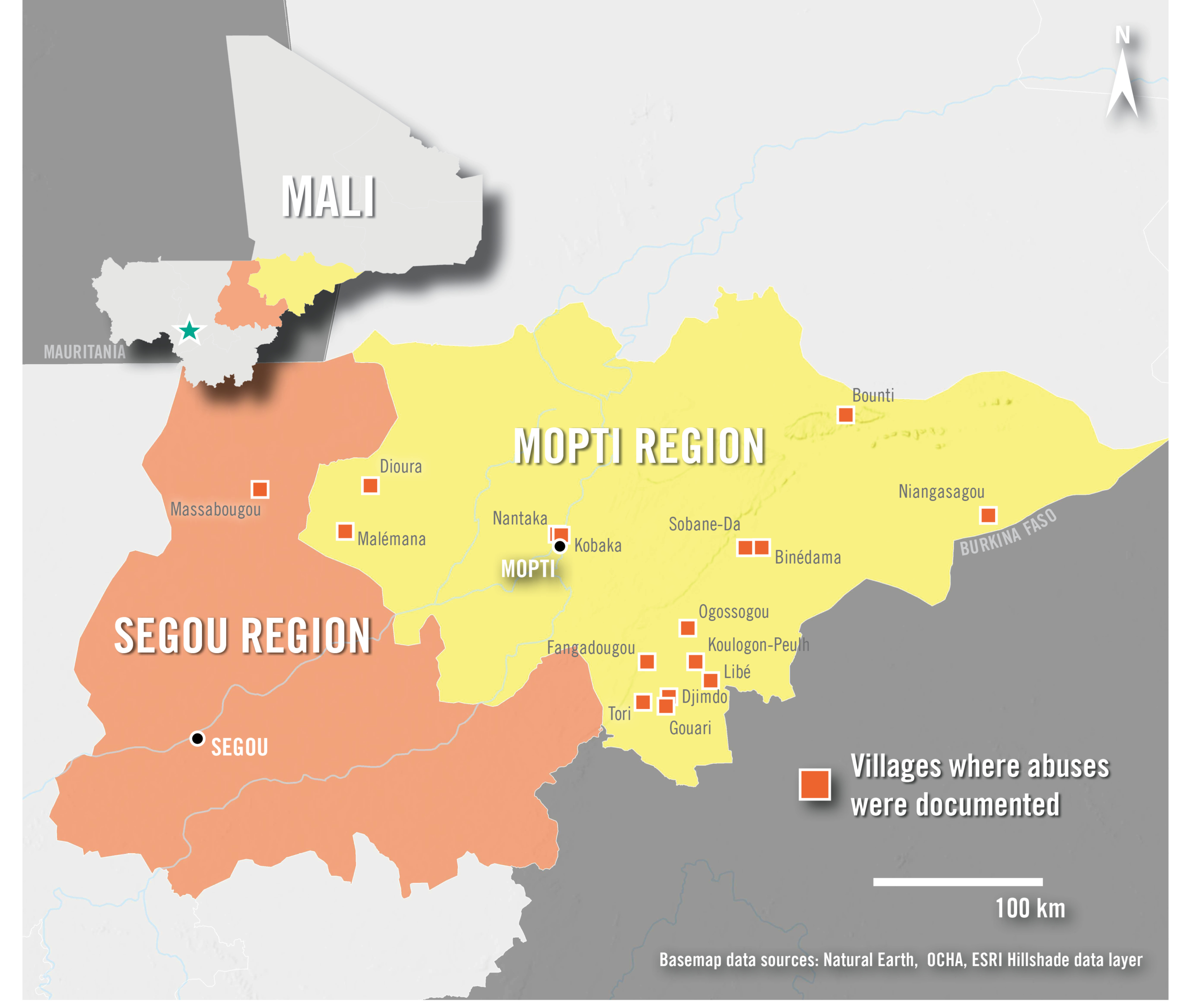

Map showing some of the villages where serious crimes have been committed since 2018 ©Amnesty International

“Impunity must end if we are to fulfil the right of victims and their families to justice and help ensure that such crimes against civilians are not repeated. The Malian authorities must follow through on their commitments by putting justice at the heart of their actions,” said Samira Daoud, Amnesty International’s Regional Director for West and Central Africa.

While the conflict and insecurity in the centre of the country undoubtedly hampers judicial investigations, this report shows that legislative and institutional reforms, additional technical and financial resources for the judicial system and greater political will are all needed if significant progress is to be made in the investigation and prosecution of crimes under international law, in accordance with international human rights standards.

An imperfect legal framework

One of the factors contributing to the impunity for crimes related to the armed conflict is the weakness of the legal framework. The National Concord Law passed in the wake of the 2015 Peace Agreement, establishes amnesties for “acts that may be qualified as crimes or offences (…)” but is ambiguous as to the exact temporal or material scope of such amnesties. These ambiguities need to be clarified to ensure, among other things, that amnesties are not given for serious human rights violations committed in the context of the armed conflict.

“As part of the review of Mali’s main codes of justice, the Malian authorities must bring their legal framework into line with international law and grant civil courts exclusive jurisdiction over crimes under international law.”

Samira Daoud, Regional Director, Amnesty International West and Central Africa

Moreover, while in 2019 the Specialized Judicial Unit responsible for combatting terrorism and crimes under international law (PJS) saw its jurisdiction extended to the entire national territory and all crimes of international law, in practice, the military justice system still exercises its jurisdiction over crimes committed against civilians by military personnel in operations. This is in contradiction with the African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights’ Guidelines and Principles on the Right to a Fair Trial and Legal Assistance in Africa (2003), which specify that military courts should only hear cases relating to purely military offences and not crimes committed against civilians.

Other provisions, such as the July 2014 Defence Agreement between Mali and France granting French courts primacy of jurisdiction over “any act or negligence of a member of its personnel in the performance of official duties” may prevent Mali’s justice system from acting on allegations of crimes committed by French military personnel operating in Mali. This is particularly true of the French army’s bombing of a wedding ceremony in Bounti (Mopti region) on 3 January 2021 in which 19 civilians and three suspected members of armed groups were killed, according to an investigation by the United Nations Multidimensional Integrated Stabilization Mission in Mali (MINUSMA).

Barriers to justice that will have to be lifted

Judicial proceedings opened by the Malian judiciary are hampered by insecurity in the centre of the country, which limits access to crime sites on the part of investigators and investigating judges. Judicial staff remain dependent on logistical support from the Malian army and MINUSMA to gain access to certain areas. Requests from judges to execute arrest warrants or to hand over suspects to the courts –especially in the case of military personnel– are not implemented. Several investigations into emblematic cases involving crimes committed since 2018 have, for example, made little to no progress. This is particularly true of investigations into the unlawful killings and extrajudicial executions, some of which constitute war crimes, committed in Ogossagou, (157 people killed in March 2019 and 35 in February 2020), Sobane Da (35 people killed in June 2019), Nantaka (25 people killed in June 2018), Massabougou (9 people killed in June 2020), Binédama and Yangassadiou (37 and 15 people killed in June 2020 respectively).

As testified by one of the judges involved in investigating these cases: “The priority right now is to ensure a state presence [in areas where it is absent], not access to justice. An investigation has been opened but it takes time. These are crimes for which there is no statute of limitations and so the Specialized Judicial Unit have all the time they need. And, let’s face it, in many of these incidents, an investigation is not possible [at this stage].”

The lack of protection for victims and witnesses is another barrier to ongoing investigations because there is a real risk of reprisals. “In the villages, everyone knows each other. There’s no point in kidding ourselves: everyone knows who has spoken to the justice system,” said an investigating judge interviewed by Amnesty International.

At a time when investigations into crimes suffered by the population in the centre of the country are stalled, however, the Malian authorities are expediting legal proceedings for acts allegedly perpetrated in those very same regions for what they call “terrorism” and which do not concern crimes committed against civilians. In October 2021, the Malian authorities held a special trial session during which 47 cases were heard. Some of these proceedings are marred by serious violations of the rights of the accused, who are detained incommunicado by the General State Security Directorate (DGSE), sometimes without charge and possibly suffering torture or other ill-treatment, for weeks or months before being sent to trial. These people often only see a lawyer on the day of the trial and their case is fast-tracked through the court. These practices on the part of the DGSE, an intelligence agency with no connection to the judiciary, are contrary to Mali’s obligations to protect human rights, in particular the right to be detained in humane conditions and the right to a fair trial.

“They kidnap you and you don’t even know who they are. Then the judges play into the hands of the DGSE,” said a civil society actor. “The DGSE isn’t a detention facility, but it is us (the justice system) that keep people there. The Bamako prison is a sieve,” said a judge interviewed by Amnesty International.

The state must end all incommunicado detentions of individuals within the DGSE and prevent the DGSE’s unlawful intrusion into ongoing legal proceedings. In the meantime, access must be facilitated to the National Commission for Human Rights, the ICRC and MINUSMA, to places of detention, under the control of the DGSE.

Unlawful detentions within the DGSE must cease immediately and the authorities must investigate all allegations of torture in custody. Suspects must have effective access to a lawyer from the moment of their arrest.

Samira Daoud, Regional Director Amnesty International West and Central Africa

A way out of this impasse

Impunity for the most serious crimes only encourages their repetition and the cycle of violence thus continues. The Malian state has an obligation to respect human rights, international humanitarian law and the right of victims to justice and truth and this must not be subordinated to a security imperative.

“We are calling on the Malian authorities to take action to protect victims and witnesses and, with the support of their partners, to strengthen the technical, financial, and human capacity of the judiciary so that it is able to ensure that all persons suspected of crimes under international law are prosecuted and tried in fair proceedings,” said Samira Daoud.

Methodology

This report is based on a series of interviews conducted by Amnesty International during two research missions to Bamako in June and October 2021, analysis of legal and judicial documents, surveys and other reports, and observation of judicial proceedings in Mali. A total of 35 people were interviewed as part of this research, including members of the government, the Specialized Judicial Unit responsible for combatting terrorism and transnational organized crime (PJS), the Mopti Court and the Bamako Appeals Court, investigators from the Specialized Investigation Brigade (BIS), judges from the military courts of Bamako and Mopti, lawyers, and members of civil society involved in some of the judicial cases.