On 10 December 1948, the General Assembly of the United Nations adopted the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR). A response to the horrors of World War II – a conflict which saw 17 million people murdered because of their ethnicity, political views, sexual orientation or physical or mental disabilities – the UDHR laid out, for the first time in human history, a set of human rights that people should enjoy regardless of nationality, gender, colour or religion.

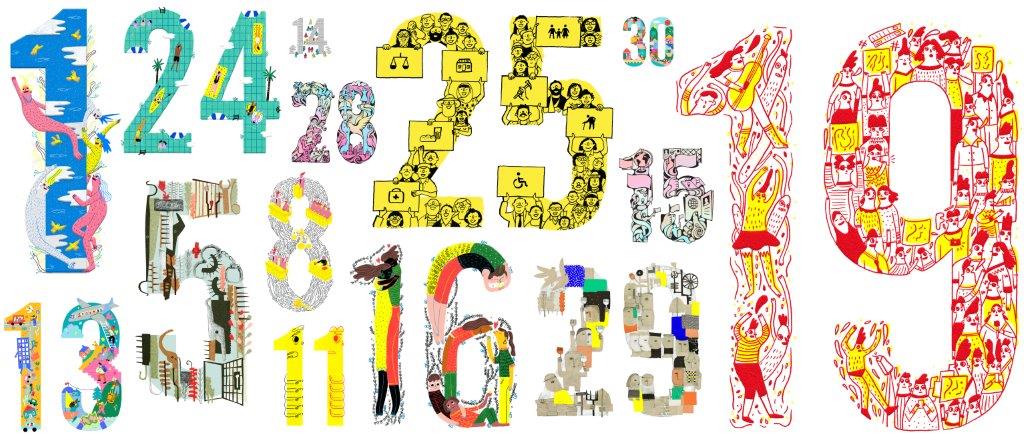

The UDHR contains 30 articles setting out human rights including the right to be free from torture, the right to freedom of expression, the right to education and the right to seek asylum. It includes civil, political, economic, social and rights, such as the rights to life, liberty and privacy, the rights to social security, health and adequate housing.

The UDHR continues to form the basis for today and it remains the most translated human rights document in the world.

Seventy years on from that momentous occasion, Amnesty International spoke to four activists born in or before 1948 to understand what the UDHR means to them and what its relevance is today.

Dora Barrancos (78), from Argentina, has been involved in human rights activism, especially women’s rights for as long as she can remember. She is tireless and will keep fighting for human rights.

“Although I haven’t always been involved with human rights organisations, I think I’ve been a human rights activist for as long as I can remember, but I’ve definitely become more active and hands-on in the fight for human rights since I became a feminist in the 1980s.

Dora believes the UDHR has been fundamental in providing the platform for extending human rights into new areas such as civil rights, political rights and gender identity rights.

“For my generation, the UDHR has been a driving force, supporting campaigns on equality and justice. My message for the younger generations is: conviction, conviction, energy, plenty of defiance and a great deal of courage for all these challenges!”

Gitu wa Kahengeri, from Kenya, is part of a select group of people who remember the day the UDHR came into being. Now aged 93, as a young man growing up under British colonial rule, he had witnessed terrible human rights abuses first-hand.

At 17 years old he quit his job and joined the struggle for independence. It was a battle he persisted with despite being moved from one detention camp to the next, enduring torture and hard manual labour. He was once beaten in front of his father.

When the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) was signed, Gitu remembers how the rights described in the Declaration guided Kenyans in their demands for sovereignty, dignity and freedom. Kenya finally gained independence from Britain in 1963.

To the younger generation, he emphasizes that there is no progress without sacrifice.

“Fighting and speaking up for the oppressed is how the younger generation can achieve an independent country where all humans are free and equal. Nothing worth doing is ever easy,” Gitu says.

Helen Thomas’ life is inextricably linked with the UDHR. A long-time activist for human rights, the UK citizen witnessed the devastating consequences of human rights being denied to people during apartheid in South Africa in the late 1960s, and later in India during the Maharashtra drought.

By a strange quirk of fate, she was born on the very night that the final text of the Declaration was agreed. Although it has become central to the way she thinks about the world, the UDHR was not something Helen was always aware of – far from it in fact. For Helen, the story of the UDHR, its origins and its significance, is one that needs to be more widely told.

“Many decades passed before I understood the monumentality of what had happened in the moments of my birth. Every person is born free and equal in dignity and rights, yet at school my children, like me, were not taught of the Universal Declaration’s existence. How can we protect our freedoms if we don’t know where they stem from?”

Helen also believes that greater education on the UDHR is fundamental to safeguarding human rights in the long term.

“To sustain them, I believe they must be known and understood by the many. We must educate every child about the Universal Declaration, why it matters, and all the human rights that they possess.”

Coming from a family of social justice activists, Amnesty International was always going to be a likely home for Canadian Will Bryant, who was just 10 weeks old when the Universal Declaration of Human Rights was signed.

“I hate injustice with a passion! I joined Amnesty International in 1973, just a few months after the Canadian Section was formed. John Humphrey, one of the authors of the UDHR, was the first president of the Canadian Section. I was energized by the idea that individuals could speak directly to governments and demand justice, demand change”

“In my lifetime I want to see human rights respected everywhere. I’ve witnessed peace come to Northern Ireland, and respect for human rights restored in Chile. Now I want to see human rights respected in places like China and Myanmar, and an end to the backsliding on human rights in the U.S. I want to see a world that’s more welcoming to refugees.”

“My message to the younger generation is to keep getting involved, stay committed, continue to lead, and never give up. You’re the present and the future. If you don’t fight for justice, who else will?”