With less than four years until the 2022 FIFA World Cup kicks off in front of 86,000 fans at the Lusail Stadium, and billions watching across the world, Qatar’s record on migrant workers’ rights remain firmly in the spotlight. While Qatar has finally begun a high-profile reform process promising to tackle widespread labour exploitation and “align its laws and practices with international labour standards”, workers still continue to be vulnerable to serious abuses including forced labour and restrictions on freedom of movement.

Migrant Workers in Qatar

Background: longstanding abuse of migrant workers in Qatar

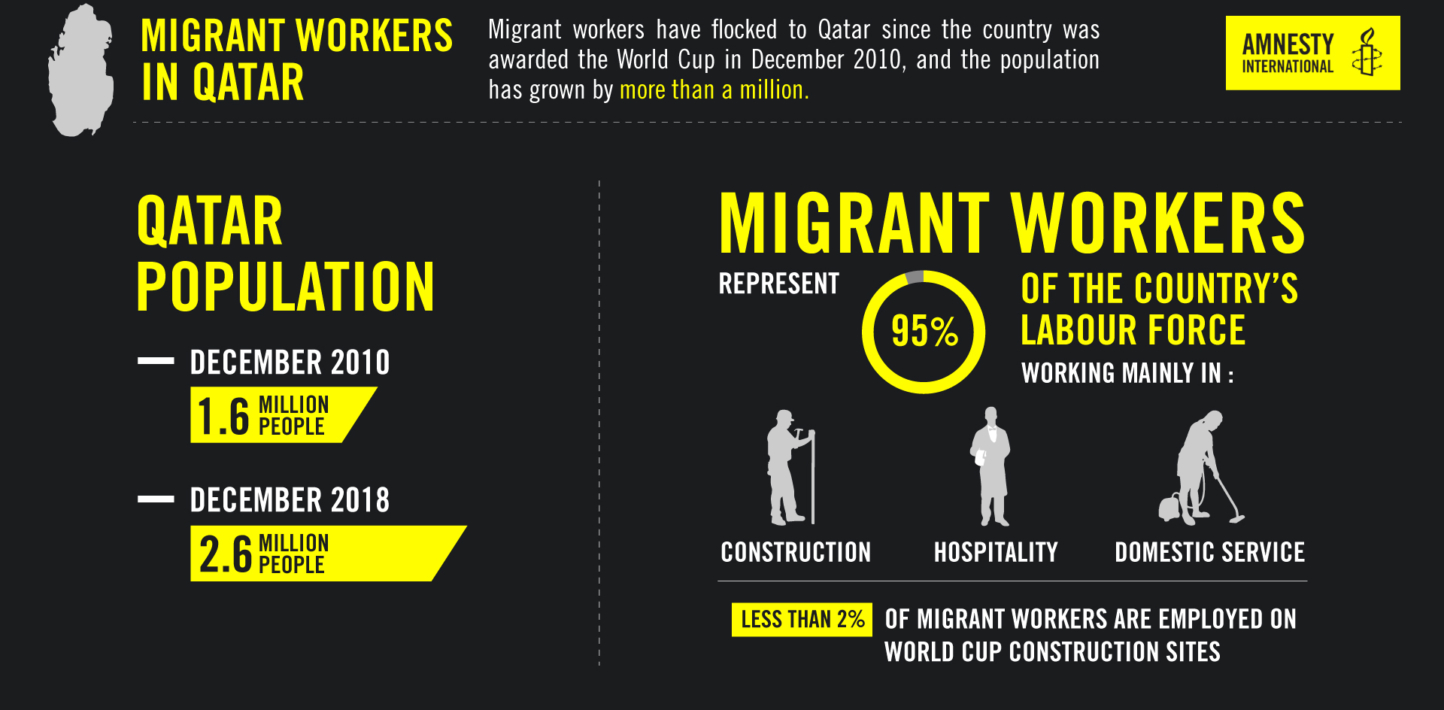

Since 2010, when the country was awarded the right to host the 2022 World Cup, Qatar’s migrant worker population has rapidly expanded. Driven in part by the subsequent construction boom, the country’s population jumped from 1.6 million people in December 2010 to 2.7 million in October 2018. Coming from some of the world’s poorest countries, and working in sectors including construction, hospitality and domestic service, migrant workers make up 95% of the country’s labour force. Yet with rapidly increasing numbers of workers travelling to take advantage of economic opportunities, more also fell victim to Qatar’s exploitative labour system.

The abuse and exploitation of low paid migrant workers, sometimes amounting to forced labour and human trafficking, have been extensively documented since the World Cup was awarded to Qatar. In October 2013, for example, The Guardian reported that 44 Nepali workers had died in Qatar in just a two-month period, while Amnesty International reports in 2013 and 2016 documented large scale labour abuse in the construction sector, including forced labour, such as at Doha’s Khalifa Stadium. In 2014 the UN Special Rapporteur on Migrant Rights also described how “exploitation is frequent and migrants often work without pay and live in substandard conditions”, and called for the country’s sponsorship system to be abolished.

Despite nascent reforms, such labour abuse continues on a significant scale today. In September 2018, Amnesty International published an investigation into an engineering company called Mercury MENA that had left dozens of workers stranded and penniless, eventually feeling obliged to return home in debt despite being owed thousands of dollars of wages and benefits. The workers had been involved in building vital infrastructure serving the city and stadium hosting the opening and the final matches of the 2022 World Cup. In a separate high-profile case first reported in May 2018, a group of 1,200 workers went unpaid for several months and went weeks without running water or electricity.

Kafala at the Heart of the Abuse

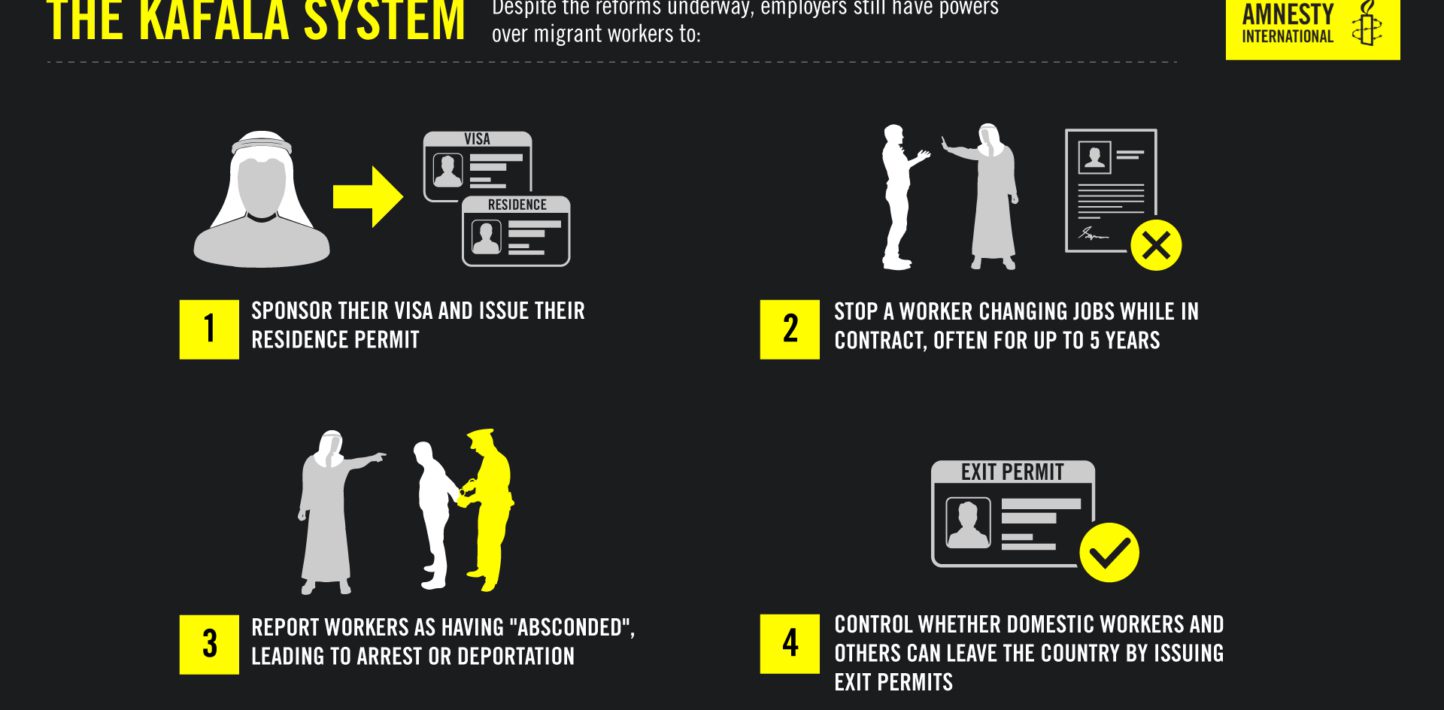

At the heart of the abuse faced by migrant workers is the persistence of Qatar’s ‘Kafala’ system of sponsorship-based employment which legally binds foreign workers to their employers, restricting all workers’ ability to change jobs and still preventing many from leaving the country without their employers’ permission.

The Kafala System

Other Factors Leading to Abuse

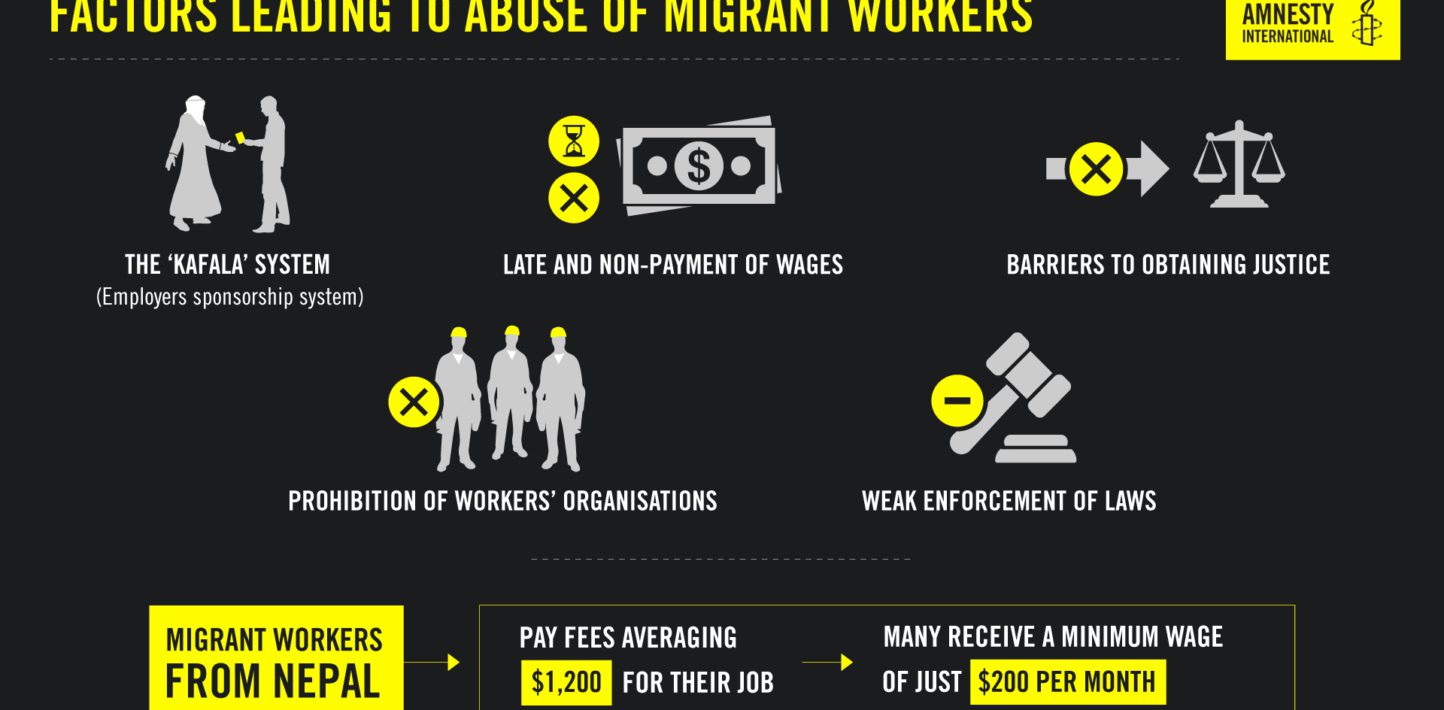

Other factors linked to this high levels of worker debt caused by illegal and unethical recruitment practices, the late and non-payment of wages, barriers to obtaining justice when rights are violated, the prohibition of trade unions and the failure to enforce labour laws.

Factors Leading to Abuse of Migrant Workers

Beyond the spotlight of the World Cup and Qatar’s broader construction boom, the country’s domestic workers also remain acutely vulnerable to abuse and excluded from some key protections and reforms.

Female domestic workers are the most vulnerable group of foreign workers in the Gulf. More than 174,000 domestic workers are employed in private households in Qatar. The majority are women, often from South Asia, providing childcare, cooking and cleaning for Qatari and other families, while there are also some men working in jobs such as drivers and gardeners. Their isolation in the home away from the public gaze and their direct dependence on their employer means they are particularly exposed to being exploited and abused.

Domestic Workers

The promise of reform

Following years of promises but limited action, in November 2017 Qatar signed an agreement with the UN International Labour Organisation (ILO) that has given rise to greater optimism. Now with an office in Qatar, the ILO is working with the authorities on a wide-ranging reform process that includes five strands of work: reform of the sponsorship system, access to justice, worker voice, health and safety, and pay and recruitment.

Since 2017, the government has passed several pieces of new legislation aimed at benefiting migrant workers, including setting a temporary minimum wage, introducing a law for domestic workers, setting up new dispute committees and establishing a workers’ support and insurance fund. It has also ratified two important international human rights treaties, albeit indicating that it will not abide by some of their key obligations, for example on the right for workers to form trade unions. It has also partially reformed the Kafala system without completely abolishing it, ending the ‘exit permit’ requirement for most workers, meaning those benefiting should now be able to leave the country without their employer’s permission.

However, despite these welcome reforms, the reality for many migrant workers in Qatar remains harsh and will continue to be so until the reform process is completed, far better implemented in practice and applied to all workers. For example, 174,000 domestic workers remain among several categories of workers still excluded from the abolition of the exit permit, the temporary minimum wage remains very low (around $200 per month), poor enforcement of laws remain a major barrier to real progress on the ground, and in hundreds of current cases new dispute committees are still taking many months to hear cases – and may still fail to ensure payment when companies will not or cannot pay. Many workers have had to return home penniless as a result.

Perhaps most strikingly, there has been no meaningful reform of the prohibition of workers’ changing jobs without the consent of their employer, through the requirement to obtain a ‘No objection certificate’. This means it is fair to say that the Kafala system remains firmly in place as a central pillar of an abusive labour system that continues to prevent workers from escaping exploitation and abuse.

All Work, No Pay

In March 2018, Qatar established the Committees for the Settlement of Labour Disputes (Committees). Replacing thenotoriously ineffective labour courts, the Committees were one of the most encouraging steps in Qatar’s labour reforms; promising to resolve their complaints and give workers a legally enforceable judgement within six weeks.

But Amnesty International’s research – focused on 2000 workers from three companies – has found that Qatar is still falling short of providing workers adequate access to justice. The new Committees are simply overwhelmed. Too many cases for too few judges means that workers are waiting months – sometimes up toeight – for their complaints to be processed. In those cases where workers do receive positive judgements, a lack of effective enforcement means that companies are too often failing to pay the compensation ordered, forcing workers to continue their fight at the civil courts in an attempt to retrieve their money.

Having been abandoned by their companies, with no pay for months and a lack offood and water, workers survive on charity handouts, their dire situations meaning many feel little option but to leave Qatar and return home with empty pockets.

If Qatar is to change course and meet its commitments on improving access to justice, it needs to take action swiftly to increase the capacity of the Committees to manage cases; enhance their ability to hold perpetrators to account; and get the Workers’ Support and Insurance Fund up and running as soon as possible so that workers can finally get what they are owed.

All Work, No Pay

Qatar’s new labour dispute committees: migrant workers still struggling for justice.

What Qatar Has Done So Far

What should Qatar do?

With less than four years until the World Cup kicks off, and more than a year since the ILO agreement was signed, it is essential that the Qatari authorities accelerate their efforts to truly transform the protections available to their migrant worker population.

Supported by the ILO, and encouraged by its partners, the Government of Qatar should:

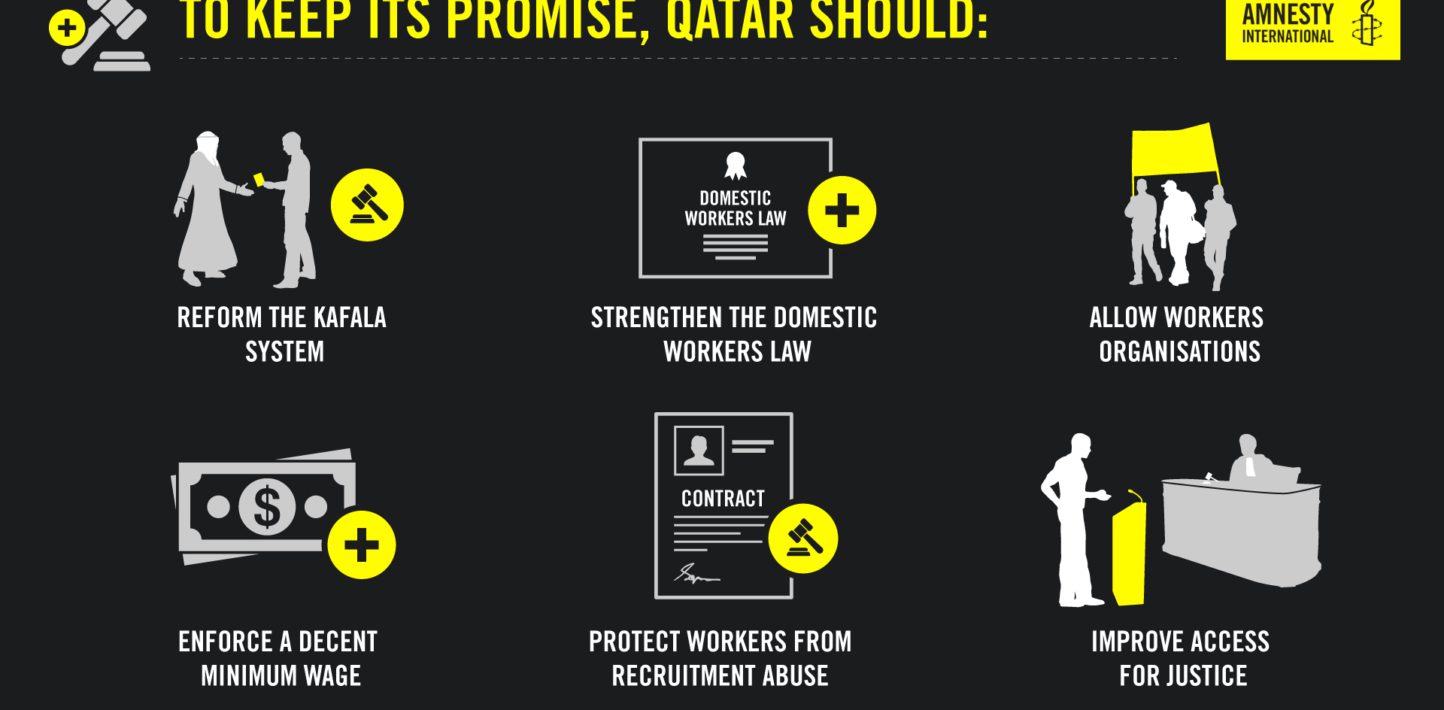

- Fundamentally reform the kafala system: allow all migrant workers to change jobs without their employers’ permission, decriminalise the charge of ‘absconding’, extend the abolition of the exit permit to all workers, and enforce the ban on passport confiscation.

- Tackle worker debt and ensure payment of decent wages: strengthen measures to protect workers from abusive recruitment practices; establish, regularly review and enforce an adequate minimum wage for all workers; ensure the Wage Protection System leads to remedial action in cases of persistent non-payment; and adequately resource the Workers’ Support and Insurance Fund.

- Strengthen enforcement of labour laws: ensure regular and rigourous labour inspections, including by increasing the number of inspectors speaking languages other than Arabic and English; hold accountable any employer or sponsor failing to respect Qatari laws and regulations;

- Improve access to justice and workers’ voice: ensure Labour Dispute Resolution Committees are resourced to be able to review cases within the legal timeframe; allow the formation of trade unions and withdraw the related reservations to international treaties.

- Strengthen protection of domestic workers: bring the domestic workers’ law in line with international standards, for example in relation to working hours; reinforce enforcement mechanisms and provide protection to victims; hold abusive employers to account, including through criminal prosecution.

What Qatar Should Do

What about FIFA and companies in Qatar?

Responsibilities and solutions do not only lie with the Qatari government. The UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights makes clear that companies must – at a minimum – respect human rights, including the rights of workers. This means taking adequate measures to prevent, mitigate and – where necessary – redress human rights abuses connected to their operations. Under no circumstances should companies take advantage of the flaws in Qatar’s labour system to exploit workers.

For entities like FIFA, this means having an ongoing responsibility to both prevent abuses and to address those that have occurred as a result of their business operations linked to the World Cup. This means, in line with its own Human Rights Policy, FIFA should not only ensure the respect of labour rights in the construction of World Cup stadia, but also use its leverage to ensure rights are respected in a broader range of infrastructure projects needed for delivery of the 2022 World Cup. This would include, for example, the cooling systems or accommodation complexes highlighted in the Mercury MENA case, key transport projects and the hospitality sector.

With the clock ticking, FIFA should also proactively seek to influence the Qatari authorities to fully and quickly deliver on their promised reforms, so that the protection of all migrant workers in the country may be a positiveand enduring legacy of the 2022 World Cup.

Other stakeholders including other governments, national football associations and sponsors can also add their voices and play an influential role at this critical juncture.

Download the full report in PDF

Reality Check: The State of Migrant Workers’ Rights with Four Years to Go Until the Qatar 2022 World Cup