When 35-year-old bus driver Saúl* and his two young children were shot at point blank in plain daylight in a quiet street in Tegucigalpa, the capital of Honduras, he knew the only way to survive was to leave the country altogether.

Honduras is one of the most violent nations on earth, where more people are killed each day than in most countries. Saúl was scared that he and his family would be targeted again.

A couple of months after the attack, the police had done nothing to protect him and his family. So Saúl collected all the cash he could get his hands on, packed a small bag and made his way to Mexico.

The plan seemed waterproof.

Bus drivers like Saúl are well known targets for the ruthless criminal gangs that control much of Honduras. They threaten drivers and force them to pay hefty “taxes” to avoid being killed.

Having survived several attacks in which his sons were nearly killed, Saúl was a perfect candidate for asylum in neighbouring Mexico. Once he got it, he would send for his wife and children.

Or that is what he thought.

Governments in El Salvador, Guatemala and Honduras are effectively forcing thousands of people to run north in search for safety.

Home Sweet Home? Central America’s refugee crisis

Murder rates

“Something will happen to me”

But there was a problem. Like many in his situation, Saúl did not get asylum in México. Instead, he was pushed back to Honduras, to the very same neighborhood where the men who had shot him still lived – controlling everybody’s lives.

Back home, Saúl and his family were left completely unprotected. He said the police told him to look for the men who attacked them himself.

I feel like something is going to happen to me

Saúl said a few days before he was killed in Tegucigalpa, Honduras

“I feel like something is going to happen to me,” he told us in his home in Tegucigalpa, three weeks after he was forced to return. He felt he needed to leave town immediately but had no money. He had spent it all during his first attempt to seek asylum in Mexico.

No one seemed to think Saúl was in real danger. They were wrong.

Because on 10 July 2016, Saúl was shot dead.

Today, his widow is terrified of what might happen to her and her children.

Deportations from Mexico

War-like violence

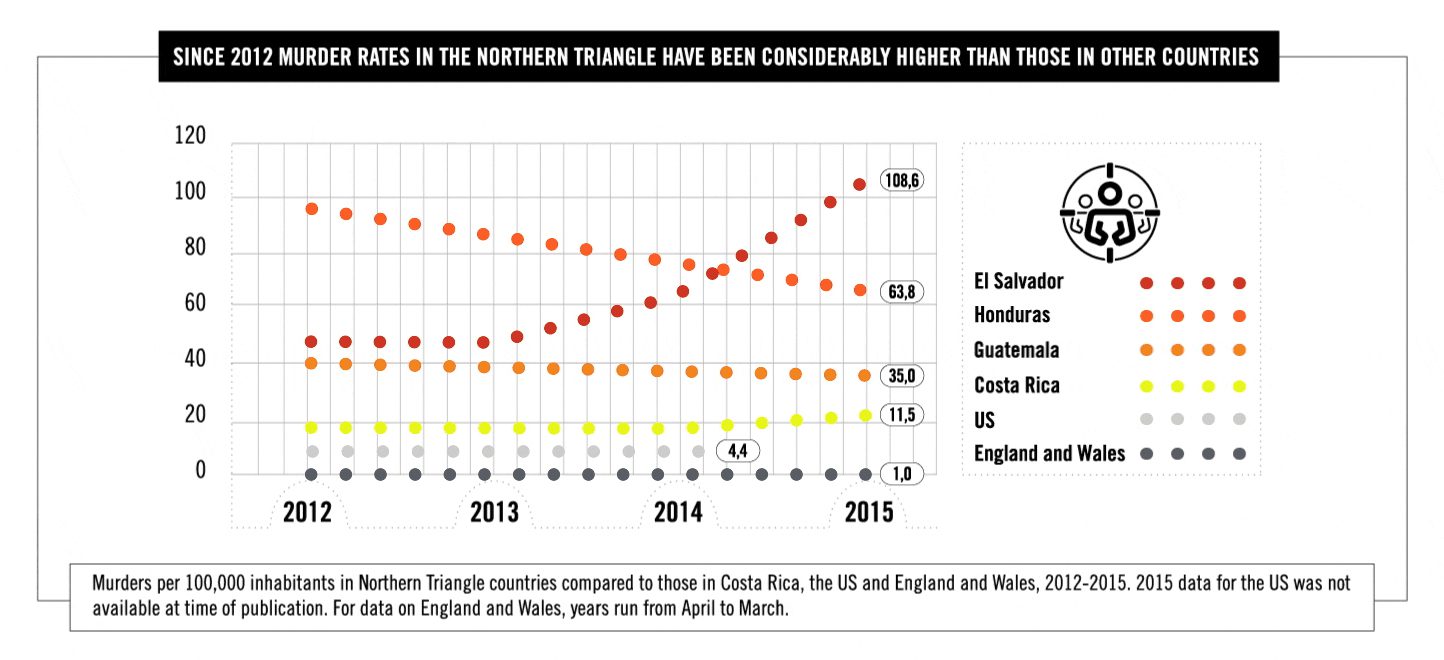

Santos’ tragic story illustrates what life is like for hundreds of thousands of men, women and children in Honduras, El Salvador and Guatemala. These are three of the most dangerous countries on earth, with homicide rates several times higher than the global average.

Vicious criminal gangs control large areas of these countries – forcing young boys to join them, girls to become sexual slaves, shop owners and bus drivers to pay hefty taxes and killing anyone who dares to say no. By failing to tackle this crisis, governments are effectively forcing thousands of people to run north in search for safety.

The numbers say it all.

According to the United Nations Refugee Agency, UNHCR, the number of people from these three countries applying for asylum around the world has increased seven-fold since 2010.

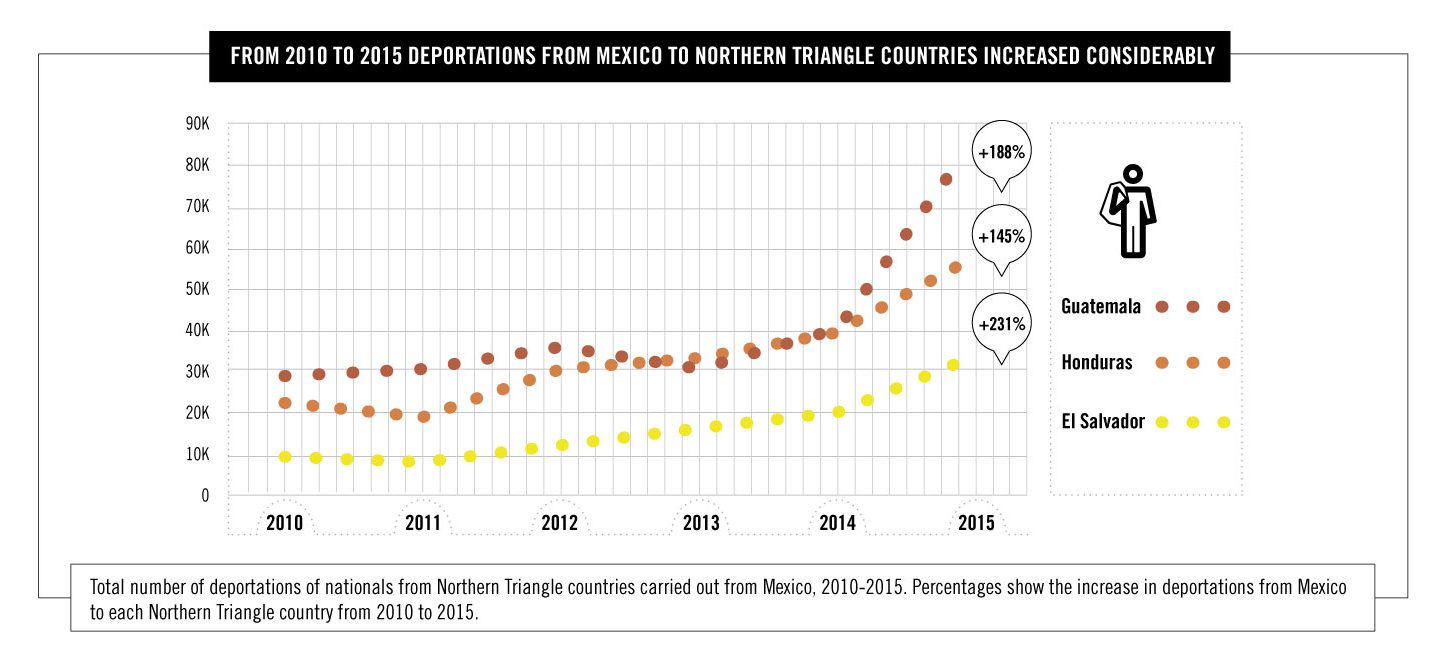

There is overwhelming evidence that these people face extreme violence and potential death if they are not granted refugee status. Nevertheless, deportations from countries, including Mexico and the USA, have increased since 2012.

The number of Guatemalans, Hondurans and Salvadorans deported from Mexico increased by nearly 180 percent between 2010 and 2015.

Thousands of people like Saúl are being pushed back to the hell they were forced to escape from. And no one with enough power to change the situation seems to be taking action.

Protect Central American refugees from brutal violence

El Salvador, Honduras and Guatemala must ensure that deportees are protected from danger when they return to their home countries.

To the governments of Guatemala, Honduras and El Salvador

We are calling you to:

- Protect your people from violence.

- Assume central responsibility for the protection of deportees using the resources required given the demand caused by the increase in numbers of deportees.

- Identify deportees-at-risk to provide them with specific protection given their particular needs

- Ensure protection programmes for deported migrants take into consideration the rights and specific protection issues relating to groups such as women, indigenous people, LGBTI people and unaccompanied children.

- Assess individual cases for re-admission asylum procedures.

Central America’s refugee crisis

Young people at the mercy of gangs

Amnesty International has found that Central American countries are doubly failing their own people: they are not doing enough to tackle the shocking levels of violence that force thousands to flee and leave them unprotected when they are deported back.

Saúl’s story is a devastating example of a growing trend affecting Central America’s young people in particular – half of all homicide victims are young men and boys.

Teenage boys and girls across the three countries live at the mercy of brutal criminal gangs. They effectively control where people can walk, what they can say, what they wear. For many, even going to school has become so dangerous they had to stop.

El Salvador’s Ministry of Education has reportedly said that 39,000 students left school due to harassment or threats by gangs in 2015 – three times the 2014 figure of 13,000. The country’s teachers’ union said they believed the real number could be more than 100,000.

Andrés* is one of those desperately trying to leave his home country, El Salvador.

The 16-year-old said he’d never been involved with a gang. That didn’t matter to the security forces who detained, kicked, beat and paraded him in front of TV cameras in May 2016. They poured water down his throat to simulate drowning to make him confess to being a lookout for one of the most powerful gangs in El Salvador.

When Andrés was eventually released, his mother filed a complaint about his ill-treatment with the Human Rights Ombudsman’s Office and the Attorney General’s Office. The investigators recommended that he shouldn’t return home, but couldn’t offer him any form of protection.He now lives in hiding, desperate to leave El Salvador.

The writings on the wall

Whose prosperity?

Governments in Central America often argue that they lack the resources necessary to tackle the overwhelming security crisis in their countries.

But in 2015, the US government set up a US$750 million fund for El Salvador, Honduras and Guatemala to tackle violence at home and stop their citizens from trying to reach the USA. The European Union and others followed suit in approving funds to curb the push factors of migration.

But very little is being done in El Salvador, Guatemala and Honduras to help those whose lives depend on protection from the authorities. And one big question remains: where is the money going?

There is no simple solution for this deep rooted, hidden refugee crisis. Tackling these countries’ murder rates and making them safe will be a very challenging task. But governments cannot afford to do nothing. It is their responsibility to protect those who have nowhere left to turn, and protect people like Saúl from being mercilessly killed.

*Names have been changed to protect the safety of the individuals and their families.