Irish psychiatrist Veronica O’Keane on Ireland’s controversial abortion law, the Protection of Life During Pregnancy Act, which came into force in January 2014

I am a consultant psychiatrist and a professor of psychiatry at Trinity College Dublin. I am also a woman who has lived under a misogynistic legal system all my life, in a country that purports to be a liberal “western democracy”.

Until 2013,women in Ireland had no effective legal right to an abortion even if their life was at risk. The right to have an abortion if you were in danger of dying was established in the Constitution following two referendums, but the government did not enact a law to support that right. This was despite the fact that in both referendums, the Irish people voted in favour of a woman’s right to abortion in life-threatening circumstances.

The need to introduce such a law came to a head when Savita Halappanavar was allowed to die in October 2012: her obstetrician waited until the foetus was dead instead of giving her the abortion that she had repeatedly requested. There was also mounting pressure from the European Court of Human Rights to enact a law.

The government finally began drafting a law, which would later become the Protection of Life During Pregnancy Act. Although most people supported a law that would allow abortion for obstetric reasons, they were divided on the case of suicide.

I am a woman who has lived under a misogynistic legal system all my life, in a country that purports to be a liberal “western democracy”.

Dr Veronica O'Keane

Accessing abortion more difficult if you’re suicidal

I publicly supported the Act, urging the government not to discriminate against women who were at risk of suicide. But many argued that women might lie about having suicidal intentions so they could get an abortion.

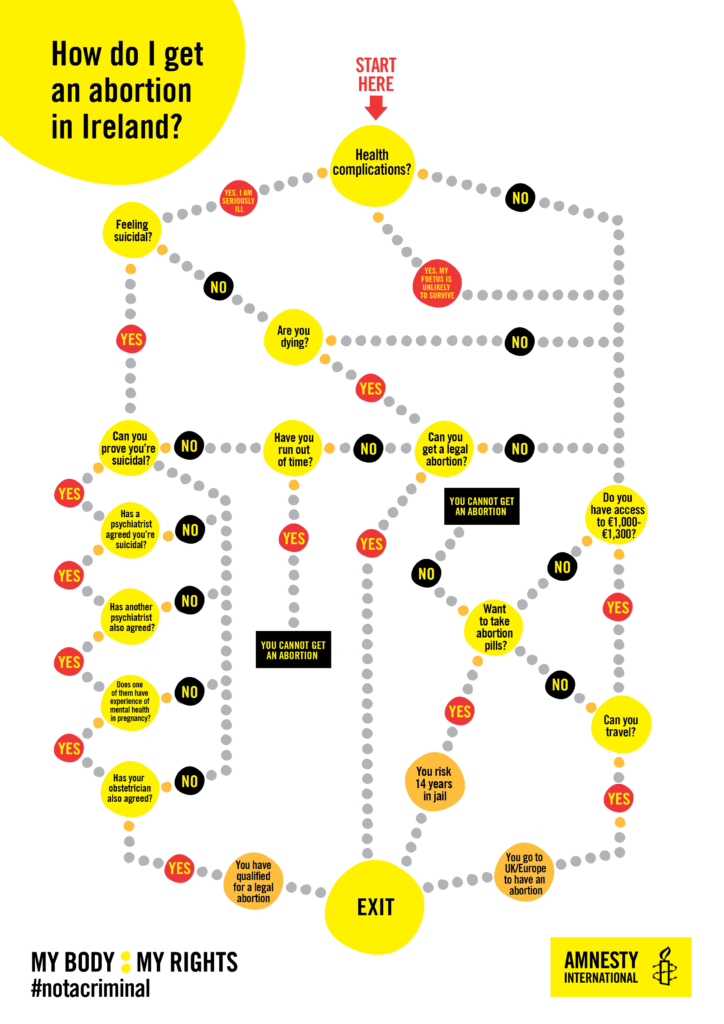

Because of this, unrealistic obstacles were put in the way of women who needed an abortion under these circumstances. For example, if a woman had obstetric complications, she would only need her obstetrician to agree to allow her an abortion. However, if she were suicidal, she would need two psychiatrists, an obstetrician and her family doctor (or a doctor in the Accident and Emergency department of a general hospital) to agree to grant her one.

Although I, and other pro-choice colleagues, argued against women being screened by at least four doctors in such cases, these pathways to care were written into the Act when it was finally passed in July 2013.

A sham law

Just after the Act was passed, a young woman, hardly more than a girl, became pregnant after being raped during wartime in an African state. Later known as Ms Y, she had fled from Africa and was seeking asylum in Ireland.

Despite telling health care workers early in the pregnancy that she was suicidal, she was not given an abortion. She became increasingly desperate and was finally forced to deliver the foetus by caesarean section at 24 weeks in an Irish hospital.

The Act was used to justify this forced delivery, demonstrating what a sham it was. Here was a woman who had clearly been at immediate risk of suicide early in her pregnancy but had not been guided towards a legal abortion. The Act had been used, not for an abortion, but to deliver a live foetus. Medical guidelines for implementing the Act, then at draft stage, were modified to allow this, and early delivery by caesarean section was classed as a “termination of pregnancy”.

Including Ms Y’s case, there were three “terminations” of pregnancy under the “suicide clause” in the first year since the Act came into force. An anti-choice politician spoke in our parliament about one of the cases, stating the place and date of the procedure. In a small country like Ireland, this compromises a woman’s anonymity. The same politician also suggested that one of the psychiatrists who certified that abortion was me. I had no difficulty with this, but it was a warning shot to other colleagues that they, too, could be identified in such circumstances.

The Act was used to justify this forced delivery, demonstrating what a sham it was.

Dr Veronica O'Keane

A day when abortion is no longer a crime in Ireland

One of the best days in the life of our republic was 22 May 2015, when the people of our country voted by a large majority to change our Constitution to allow same-sex couples the right to marry. Following quickly on this, the government passed laws allowing people in Ireland to change their gender identity, without needing specialist medical opinions.

In Ireland we are now in the unique position of having equal rights for lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and intersex (LGBTI) people while women have virtually no legal right to abortion.

Until it is decriminalized, abortion will not be available to women in Ireland. Doctors will not risk breaking the law: to do so could mean a prison sentence of up to 14 years. This is laid down in the Act.

I think Amnesty’s #notacriminal campaign has moved the debate in Ireland from extreme circumstances, such as pregnancies resulting from rape and incest, or life-threatening pregnancies. Debates about these extreme circumstances are always pitched at a highly emotive level. There is now a spreading realization that abortion care is part of general reproductive care.

I hope that the choice to have an abortion will be an entirely private matter decided between a girl or woman and her doctor.

Dr Veronica O'Keane

Amnesty’s call to decriminalize abortion in all circumstances has enabled the Irish people to look at less extreme life situations through the lens of human rights. The vast majority of women who have had and who will have abortions are choosing abortion in the spirit of responsible parenthood. They too should never be made to feel like criminals.

My hope for 2016 is that we will repeal the 8th Amendment (which gives the right to life to the foetus and places it on equal footing with that of the woman). The Protection of Life During Pregnancy Act will become redundant as its existence is rooted in the 8th Amendment. I hope that the choice to have an abortion will be an entirely private matter decided between a girl or woman and her doctor. It should be regulated with the same ethical guidelines that are an intrinsic part of medical care. Laws to limit access to abortion care will probably be demanded, but I see this as a stage in the fight to ensure full choice for women.