Amnesty International’s latest report on Cameroon documents crimes under national law and human rights violations – including unlawful killings, murders, sexual violence and abductions – committed by the Cameroon defence and security forces, militias, and armed separatists in the Anglophone North-West region in recent years. Activists and others speaking out about what is happening have faced reprisals, both from the authorities and the armed separatists.

In this context various state partners of Cameroon have continued their military cooperation and the supply of military equipment to Cameroon without providing information on any mitigating measures in place to ensure their assistance do not contribute to serious human rights violations and crimes committed by armed separatists, army forces and militias in the Anglophone regions.

Download our latest report on Cameroon

BACKGROUND TO THE ANGLOPHONE CRISIS

HOW IT STARTED

In late 2016, thousands of people in Cameroon’s Anglophone North-West and South-West regions, including lawyers, teachers, students and human rights defenders, took to the streets to denounce what they saw as the growing marginalisation of Anglophone linguistic, educational and judicial systems, and the failure to improve Anglophone political representation. Some demonstrators also called for greater autonomy or secession for Anglophone regions. The security forces responded to these largely peaceful demonstrations with brutal violence – including unlawful killings – and arrested hundreds of people, many of whom remain arbitrarily detained to this day

ESCALATION AND CLASHES

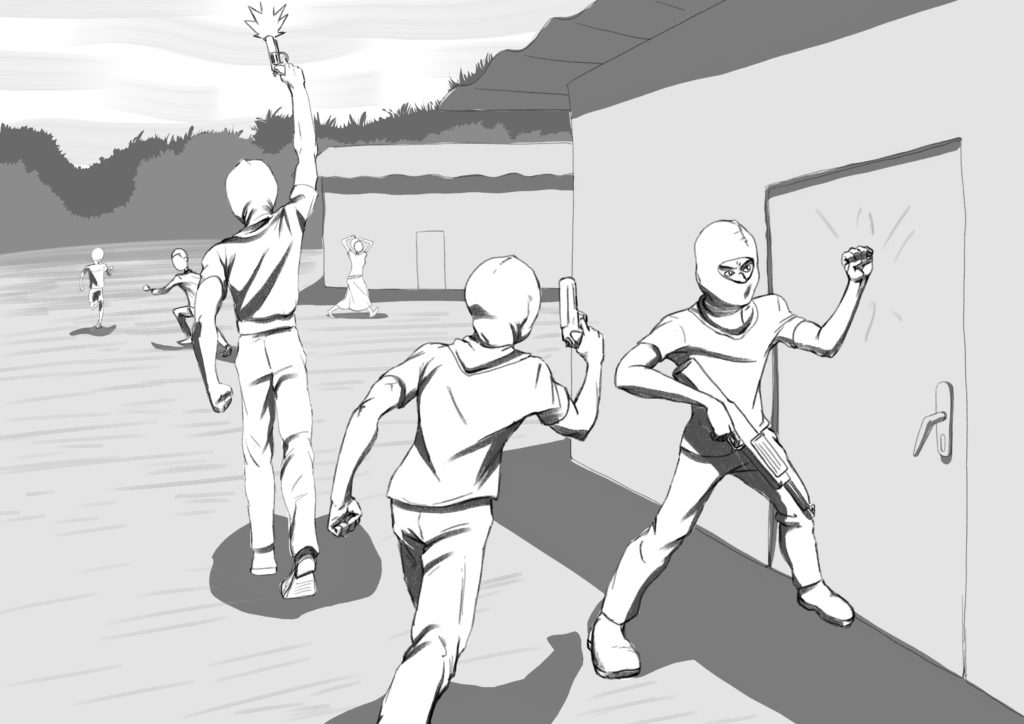

In late 2017, separatist movements emerged, proclaiming the independence of the North-West and South-West regions as the ‘Federal Republic of Ambazonia’. Violent clashes ensued between the Cameroonian military and armed separatists, known collectively as ‘Ambas’ (Ambazonians), and continue to this day. Numerous peace initiatives have failed, and armed violence has become entrenched.

Indeed, armed separatists are still very active, despite losses and divisions into various factions. They have a presence all over the Anglophone regions and are well-established in hard-to-reach rural areas. They have strengthened their weapons arsenal and continue to target state structures, including outside the Anglophone regions. Armed separatists also target anyone suspected of supporting the government, or not adhering to their cause.

Cameroonian defence and security forces also continue to lead attacks against the separatists – and against people suspected of supporting them. On both sides, it seems that people are perceived as ‘with us or against us’, and face reprisals accordingly.

LONG-STANDING GRIEVANCES AND DISCRIMINATORY AND INFLAMMATORY SPEECH FUELLING VIOLENCE

Amid the fighting between the Cameroonian military and armed separatists, long-standing land conflicts between Mbororo Fulani herders, and farmers from other ethnic groups in the North-West region, are also fuelling armed violence. The Mbororo Fulani are perceived to support the authorities and as such are particularly targeted by armed separatists. Some people have used the Anglophone crisis as a pretext to settle old disputes with the Mbororo Fulani, and there are many examples of discriminatory and inflammatory speech targeting this population, accusing them of being ‘outsiders’ and calling for their expulsion from the region. On the other hand, pro-government armed militias, mainly composed of Mbororo Fulani, have also committed abuses against the population.

Atrocities continue from all sides

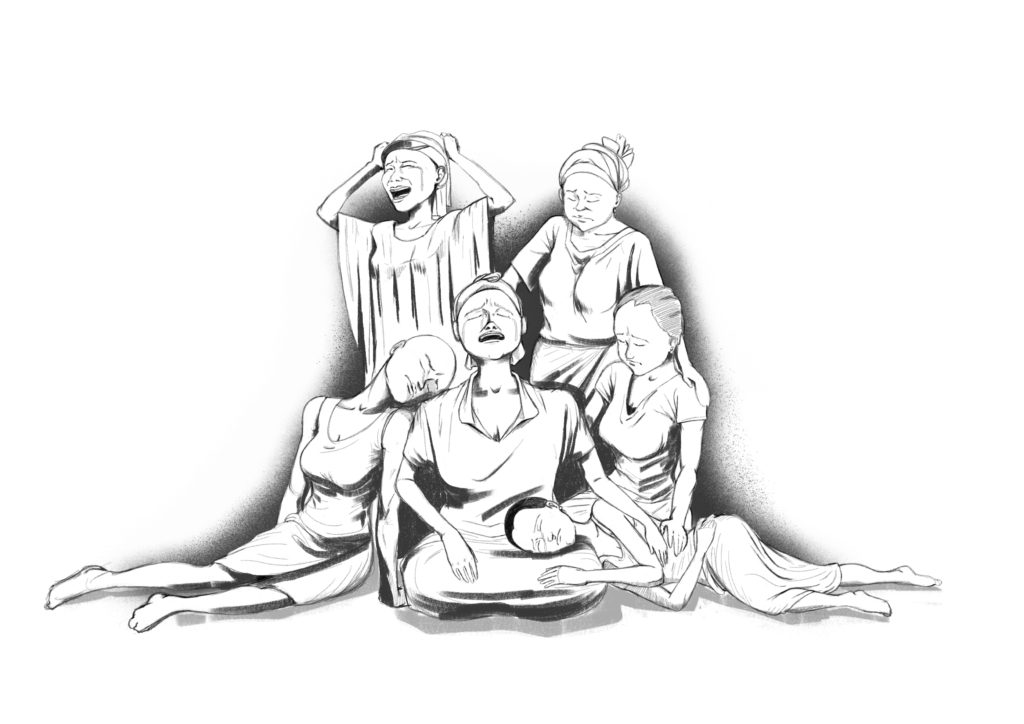

Both the Cameroonian military and armed separatists have committed atrocities against the population in the North-West region. The Cameroonian army has perpetrated serious human rights violations, including unlawful killings, sexual violence, the destruction of houses, and the harassment and detention of those speaking out about the crisis. Armed separatists have perpetrated serious crimes under domestic law such as murders, abductions, acts of torture, and destruction of houses. Although the situation does not qualify as armed conflict, all these atrocities remain absolutely prohibited under Cameroonian law and international human rights law.

CAMEROONIAN ARMY AND MILITIAS’ ATTACKS ON THE POPULATION

On 17 December 2022, members of the Cameroonian army killed three people and destroyed at least 10 houses in a village in Bui division. The incident was reported to be in retaliation for an earlier attack on the army by armed separatists in the area. A village resident shared his harrowing account with Amnesty International: he was startled from his sleep by loud noises and emerged from his home to see some of his neighbours’ houses in flames. Fearing for his own safety, he quickly ran to grab a few possessions. As soon as he came to the door he saw 11 soldiers, all in military uniforms. They asked him in French: “Where are the Amba boys you keep in the village?” When he truthfully said he did not know of the whereabouts of any separatists, one of the soldiers reacted aggressively, forcefully pushing him down and subsequently ordering fellow soldiers to set his house ablaze. A soldier who was holding a five-litre gallon of petrol, proceeded to douse the house with it and ignited the flames.

Some armed Mbororo Fulani have also been perpetrators of violence (including killings, the burning of homes and land, and stealing cattle), sometimes in collaboration with defence and security forces. For example, on 14 February 2020, Cameroonian military and armed Mbororo Fulani massacred 21 people in Ngarbuh, including 13 children.

The government has at times announced investigations and prosecutions of certain human rights violations committed by the armed forces, but beyond the opening of the trial more than two years ago on the Ngarbuh massacre, no further information has been made available on the progress of the cases, raising concerns about de facto impunity in these cases.

When I started screaming, they said: “Stop the noise or we will kill you!” I remained calm and a few minutes after my house was burned down, I left the village on foot for Jakiri, where I am currently seeking refuge.

One person displaced from Yer village

ARMED SEPARATISTS’ ATTACKS ON THE POPULATION

On the night of 28 March 2022, a horrifying incident took place in the village of Mbokop-Tanyi. Armed separatists attacked a Mbororo Fulani compound, including a home where a woman and her seven-year-old child and six-month-old baby had been sleeping. They first shot the woman, and then proceeded to burn the house with all three of them inside, killing all of them. The woman’s husband, who was not present, said that he never had “any problem either with Amba Boys or anyone in the village” before the attack. He told Amnesty International in despair: “One of my brothers called me the next morning to tell me that the Amba Boys had burned down my house, with two of my children and my wife inside.”

RAPE BY THE CAMEROONIAN ARMY

On 3 September 2021, Monica, who was just 20 at the time, was terrified as she saw the Cameroonian military arrive in her village (Ngie) and start attacking homes, apparently in retaliation for the killing of one of their troops by separatists earlier that day. She told Amnesty International how she grabbed her baby daughter and ran to hide in the house, but the soldiers kicked the door down. They ordered her husband to lie on the floor, and told Monica to leave her daughter to one side. A soldier then raped Monica. As her husband attempted to defend her, they shot him three times: in his head, his chest and his stomach. After about an hour, they took Monica and her daughter outside and set their house on fire. They drove them to an army camp, where they were held with six others. The youngest of these was just 12. Every day, they raped them one after the other. After more than 75 days, Monica and the others were released after one of the soldiers agreed to help them and alerted his commanding officer to what was happening in the camp. But by that time, three of the girls were already dead. Monica later gave birth to twins as a result of the rape.

‘Annie’ also reports that she was having dinner with her grandparents in 2021 when the Cameroonian military burst in and shot her grandparents dead, then raped her repeatedly.

They wanted to rape me. They did. A military man raped me there. My husband tried to defend us and they shot him three times in the head, stomach and chest.

Monica

HOSTILITY TARGETING THE MBORORO FULANI

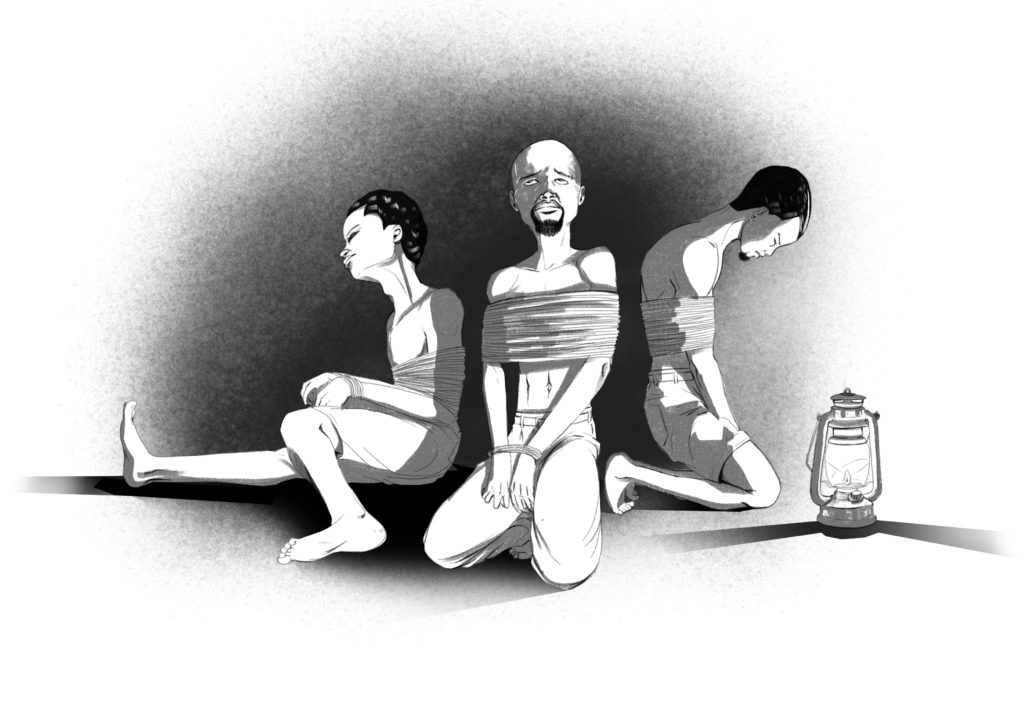

Since 2017, several hundred Mbororo Fulani people have reportedly been killed in the North-West region. They are also targeted for abductions in exchange for ransom, and armed separatists have been burning their homes and taking their cattle. For example, Mohamed, a Mbororo herder, was told the Mbororo were not supporting the Ambas and would be driven out of the region. He was abducted on four separate occasions in 2019 and tortured with machetes, before he paid ransoms and was set free. While Mbororo Fulani have not necessarily been targeted by armed separatists more than other groups, attacks on them often appear to be accompanied or fuelled by discriminatory speech identifying them as ‘outsiders’ who should leave the Anglophone regions.

A CLIMATE OF REPRESSION

The political and judicial authorities have responded to this situation with further human rights violations. Separatist political leaders and members of civil society, including journalists, have been tried and sentenced by military courts for terrorism-related offences, even though military courts should not in any circumstances have jurisdiction over civilians according to international and regional human rights standards. People accused of being armed separatists, or supporting them, have at times been arbitrarily arrested and detained. Meanwhile, very little information has been made available on genuine investigations into the crimes committed by armed separatists against the population, leaving many victims of these crimes without justice.

Indeed, the grievances that fueled the Anglophone crisis have no doubt been exacerbated by the treatment of people by the justice system – apparent impunity for violations allegedly committed by the Cameroonian military, but many arbitrary detentions and unfair trials for the Anglophones. Indeed, more than 1,000 Anglophones remained in detention across the country as of January 2022, and many dozens of these people have demonstrably been arbitrarily arrested, sentenced and detained. These include the demonstrators whose protests marked the beginning of the crisis, alleged separatists, and activists denouncing the situation.

There have also been many apparent attempts to silence human rights defenders, activists, academics, lawyers and journalists who speak out against atrocities committed in the context of armed violence in Cameroon’s Anglophone regions. Those denouncing or documenting atrocities committed by either side have often found themselves detained, harassed and targeted with death threats.

For example, peace activist Abdul Karim Ali was taken into custody at a military base in August 2022, and has been held in detention ever since, most recently at Kondengui central prison in Yaoundé. Charges against him include ‘hostility to the fatherland’, ‘secession’ and ‘rebellion’. While he has not been shown evidence to support these accusations, he has been interrogated repeatedly about a video he made on 9 July 2022 denouncing a Cameroonian military chief known as ‘Moja Moja’ for reportedly torturing civilians.

Akem Kelvin Nkwain, a human rights officer at the Centre for Human Rights and Democracy in Africa (CHRDA) received several death threats from alleged armed separatists in 2022, after tweeting about a child killed by an improvised explosive device (IED) allegedly planted by separatist fighters. Messages included an image of himself being marked for killing, and the words: ‘We declare you and your whole entire family as traitors and enemies to the Ambazonian fighters.’

MILITARY COOPERATION

Since the beginning of the armed violence, the Cameroon government has invested significantly in resources for the military. On the other side, armed separatists’ weapons are becoming increasingly sophisticated. Amnesty International has documented that they are in possession of weapons originating from various countries including Russia, Israel and Belgium, as well as weapons taken from the Cameroonian army.

In this context of armed violence riddled with multiple credible allegations of grave human rights violations, Cameroon’s international partners, including France, the United Kingdom, Belgium, Israel, Croatia, Serbia and Russia have continued to cooperate with the country militarily, including through the supply of arms and military equipment. Amnesty International underlines the risk that the military equipment provided by Cameroon’s partners could be used by army forces, militias, or armed separatists to commit crimes in the Anglophone regions.