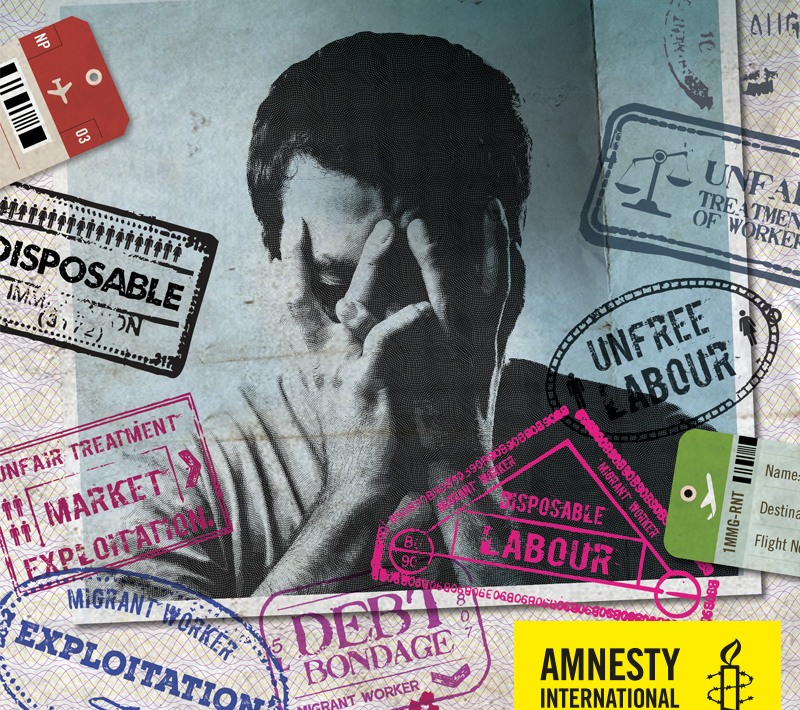

This is the first blog in a series showing light on some of the stark realities faced by Nepali migrant workers. This is the story of “Aadinath”, who accumulated a staggering debt – the equivalent of over two years of his annual income – before he had even left Nepal due to fees he had to pay a recruitment agency. This crippling indebtedness left him with no choice but to enter into exploitative working conditions. “Aadinath’s” story is not unusual.

Read Amnesty International’s new report here: Turning people into profits: Abusive recruitment, trafficking and forced labour of Nepali migrant workers.

Nepali versions of these blogs are available here.

Recruitment: lured into huge debt to get work

Before I had even left, I had spent NPR 158,000. I was earning NPR 6,000 per month at the time.

Aadinath

I live in a small village south-east of Kathmandu. For many years, I worked as a farmer. In a good month, I would earn just NPR 6,000, but business was getting tough and I was not able to earn enough to support my wife, and my two young sons. Some of my friends had gone abroad – they had found work in Malaysia or Qatar and had been able to send money home. I realised that this was a path I would also have to follow.

A man in my village, Tanuj, approached me. He had heard that I wanted to go abroad, and offered to put me in touch with a recruitment agency in Kathmandu. He had helped other people in my village find work overseas, so I trusted him – and his advice. He told me to get my passport quickly, which cost me NPR 5,000 (USD 48).

Then, Tanuj took me to Kathmandu, to the offices of the agency. Here, they told me that I had to pay NPR 145,000 (USD 1400) in recruitment fees. I was shocked – I don’t have this kind of money. The agency promised me, though, that the fee was so high because I was being sent to a good company in Malaysia. I would earn MYR 1,500 a month, and I would quickly be able to start saving and sending money back to my family.

The agency told me to hand over my passport so that they could start applying for the work visa. I did as they instructed.

I returned with Tanuj to my village, where I went to find a local money-broker. I borrowed the full amount: NPR 145,000 at an interest rate of 36% per year. I immediately had to go back to Kathmandu to hand the money over to the agency, but Tanuj didn’t come with me this time. I had to find my own way there. It took me around seven hours in total and over NPR 1,500. When I arrived, someone from the agency met me. I gave them the money and the person left. He did not give me a receipt: he said he would write one for me later. That same day, I returned to my village – another seven hours, another NPR 1,500.

After a few weeks, the recruitment agency called me and told me I would be leaving to Malaysia soon and I had to immediately come to Kathmandu. I packed my belongings – not sure exactly what I needed to bring – and said goodbye to my wife and my children. When I arrived in Kathmandu and called someone from the agency, I was told that there had been some delays and I would have to wait. I have a relative who lives close to Kathmandu, so I took a bus there – and waited.

It took one week for the agency to call me again. They arranged for me to go to a medical centre where I had pay NPR 3,500 (USD 34) to take some tests. Straight after the tests, with no delay, the doctors handed me a certificate that said I was medically fit to work abroad. I now wonder whether they had even seen the results from my tests.

After my medical exam, I called the agency and, again, they told me I would have to wait. I felt anxious, and sad: it had been a month since I had taken out the loan – the interest was already building up and I had not even left the country. I was living with my relative, not able to work, spending money I did not have on food, and I was separated from my family.

It took another five days. Finally, the agency called me and told me I would be flying that evening. They picked me up from my relative’s house. We drove around Kathmandu picking up other men who were travelling on the same flight as me.

We all got out of the car at the airport, and were each handed a pack of documents. One of them was a certificate stating that I had taken ‘Orientation Training’. I don’t even know what ‘Orientation Training’ would entail. Another was a receipt that said I had paid NPR 80,000 for the recruitment fee. And then, there was the contract…

In the contract, the name of the company was different; the work was different; the hours were different and worst of all, the salary was different. Instead of MYR 1,500 as had been promised by the agency, I saw the figures MYR 600 in front of me.

I felt despair, but I could not turn back. I had already paid around NPR 158,000 and I had not even set foot on Malaysian soil. I could not afford to turn around now and go back to my village. What choice did I have but to get on that plane?

To be continued.

Read the second blog in this series here.