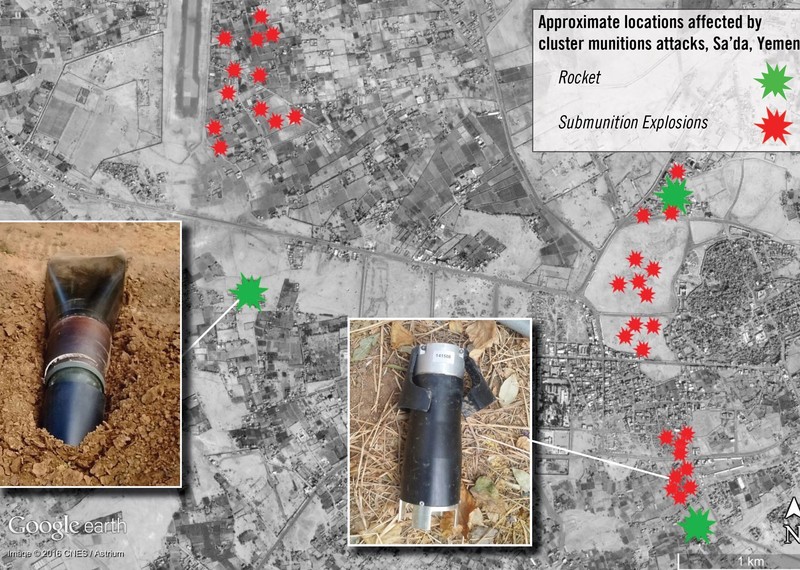

Amnesty International has corroborated new evidence the Saudi Arabia-led coalition recently fired Brazilian-manufactured rockets containing banned cluster munitions striking three residential areas and surrounding farmland in the middle of Sa’da city, injuring two civilians and causing material damage.

The attack, which took place at 10.30pm on 15 February 2017, is the third confirmed use of Brazilian-manufactured cluster munitions documented by Amnesty International in the last 16 months.

“The Saudi Arabia-led coalition absurdly justifies its use of cluster munitions by claiming it is in line with international law, despite concrete evidence of the human cost to civilians caught up in the conflict,” said Lynn Maalouf, Director of Research at the Beirut regional office.

“Cluster munitions are inherently indiscriminate weapons that inflict unimaginable harm on civilian lives. The use of such weapons is prohibited by customary international humanitarian law under all circumstances. In light of mounting evidence, it is more urgent than ever for Brazil to join the Convention on Cluster Munitions and for Saudi Arabia and coalition members stop all use of cluster munitions.”

Cluster munitions are inherently indiscriminate weapons that inflict unimaginable harm on civilian lives

Lynn Maalouf, Deputy Director for Research at Amnesty International's Beirut Regional office

Following the rocket attacks, Amnesty International interviewed eight local residents over the phone, including two witnesses – one of whom was injured in the attack. It also spoke to a local activist and analyzed photographic and video evidence provided by the national munitions watchdog, the Yemen Executive Mine Action Centre (YEMAC), which inspected the site within 30 minutes of the attack.

YEMAC staff also confirmed the use of the same type of cluster munitions in a separate attack that occurred in late January in the directorate of Abdeen, five kilometres south of Sa’da city.

Neighbourhoods affected

According to witnesses and local residents, rockets struck the residential areas of Gohza, al-Dhubat and al-Rawdha, resulting in submunitions also landing on homes in al-Ma’allah and Ahfad Bilal, as well as on the new and old cemeteries in the middle of the city, and surrounding farms.

Latifa Ahmed Mus’id, 22, described the attack in Ahfad Bilal, which took place while she was asleep at home. She was with her husband Talal al-Shihri, her three-month old son, Hasan, and three-year old son, Hussain.

“The bomb came into the house, into the bedroom from the ceiling. There is a big round hole in the ceiling. At the time, we heard a big explosion and seconds later the bomb exploded in the room and we got hurt. Three exploded right outside the house… The children were unhurt but in shock… My husband sustained shrapnel injuries on his foot. I hurt my left foot and we went to al-Salam hospital that very night.”

The bomb came into the house, into the bedroom from the ceiling. There is a big round hole in the ceiling…Three exploded right outside the house… The children were unhurt but in shock… My husband sustained shrapnel injuries on his foot. I hurt my left foot

Latifa Ahmed Mus'id, survivor of a cluster munition attack

The family fled 78km to Sa’da city four months ago after their home in Baqim, 12km south of the Saudi Arabian border was bombed.

“We were forced to leave our home in Baqim when it was bombed. The bomb went right into our living room and destroyed the house. Everyone had to leave the area. The bombardment was constant. We left two-three months after the strike on our house… We made our way to Sa’da on foot.

We walked for 20km and I was six months pregnant at the time and then a car gave us a lift to Sa’da city.”

A local resident of al-Ma’allah, one of the affected areas in the recent attack, described to Amnesty International hearing a loud explosion.

“I heard a really loud sound. And directly after I heard very dense sounds, as if something was spreading. It was so rapid and it lasted 20-30 seconds.”

Head of the YEMAC 12th team Yahya Rizk told Amnesty International about his team’s visit to the neighbourhoods of al-Rawdha and Ahfad Bilal.

“We found one carrier and one unexploded submunition in al-Rawdha. Al-Rawdha is a densely populated area where bombs [submunitions] penetrated the roofs of two houses. One bomb went through the roof and injured a man and his wife in Ahfad Bilal – it went into their bedroom at [approximately] 11pm. They were taken to the hospital the same night.

Most of the damage was to the property, houses and cars. We noted 12 impact holes in al-Rawdha, by the fruit farms. And 12-13 impact sites in Ahfad Bilal. We found one unexploded bomb [submunition] in al-Rawdha which came down from a tree and landed in the soil, which we photographed.”

Members of the YEMAC team also confirmed carrying out a sweep of residential areas in densely populated Gohza where they noted impact holes and damage to houses. Yahya Rizk said, “The bombs [submunitions] landed in people’s porches and between houses. They all exploded and no people injured. But windows were all broken and up to 30 cars damaged.”

Based on the description of the YEMAC team, and after examining photographs and videos of the aftermath of the attack, including photos of the carriers and one unexploded submunition, Amnesty International was able to identify the remnants used in the attack as being an ASTROS II surface-to-surface rocket.

The ASTROS II is a truck-loaded, multiple launch rocket system (MLRS) manufactured by Brazilian company Avibrás. ASTROS II is capable of firing multiple rockets in rapid succession, with each rocket containing up to 65 submunitions, with a range of up to 80km, depending on the rocket type.

The company’s marketing presentations describe it as being “an important defence system with great deterrent power.”

Mounting evidence

Amnesty International documented the first known use of these types of cluster munitions in Yemen on 27 October 2015 on Ahma north of Sa’da city, which wounded at least four people, including a four-year old girl.

In May 2016, Amnesty International found further evidence of the same type of cluster munitions in villages 30km south of the Saudi Arabian border in Hajjah. As recently as December 2016, Human Rights Watch also documented the use of Brazilian-manufactured cluster munitions on Sa’da city.

To date, Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch have documented the use of seven types of air-delivered and ground-launched cluster munitions made in the USA, the United Kingdom, and Brazil. The coalition has admitted using UK and US-made cluster munitions in attacks in Yemen.

“How many more civilians need to be killed, injured, or see their property destroyed through use of these internationally banned weapons, before the international community condemns the use of cluster munitions by the Saudi Arabia-led coalition and pressures coalition members to immediately become parties to the Convention on Cluster Munitions?” said Lynn Maalouf.

Background

Cluster munitions contain between dozens and hundreds of submunitions, which are released in mid-air, and scatter indiscriminately over a large area measuring hundreds of square metres. They can be dropped or fired from a plane or, as in this instance, launched from surface-to-surface rockets.

Cluster submunitions also have a high “dud” rate – meaning a high percentage of them fail to explode on impact, becoming de-facto land mines that pose a threat to civilians for years after deployment. The use, production, sale and transfer of cluster munitions is prohibited under the 2008 Convention on Cluster Munitions, which has almost 100 states parties.

On 19 December 2016, the Saudi-run Saudi Press Agency reported that the Saudi Arabian government would stop using a UK-made cluster munition, the BL-755 but contended that, “international law does not ban the use of cluster munitions” and while some states are party to the Convention on Cluster Munitions (CCM), “neither the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia nor its coalition partners are state parties” to the CCM. It further claimed that UK-made cluster munitions used by the coalition had been used against “legitimate military targets” and that the cluster munitions were “not deployed in civilian population centres” and that the coalition “fully observed the international humanitarian law principles of distinction and proportionality.”

While Amnesty International is aware of the presence of a military objective, Kahlan Military base, 3km north-east of the city of Sa’da, the presence of a military objective in itself would not have justified the use of internationally banned cluster munitions – particularly not its use on populated civilian neighbourhoods. And even though Brazil, Yemen, Saudi Arabia and members of the Saudi Arabia-led coalition participating in the conflict in Yemen are not parties to the Convention, under the rules of customary international humanitarian law they must not use inherently indiscriminate weapons, which invariably pose a threat to civilians. The customary rule prohibiting the use of inherently indiscriminate weapons applies to their use under all circumstances, including when the intention is to target a military objective.

According to Landmine and Cluster Munition Monitor, Avibrás has sold this type of cluster munition to Saudi Arabia in the past, and Human Rights Watch documented their use by Saudi Arabian forces in Khafji in 1991.