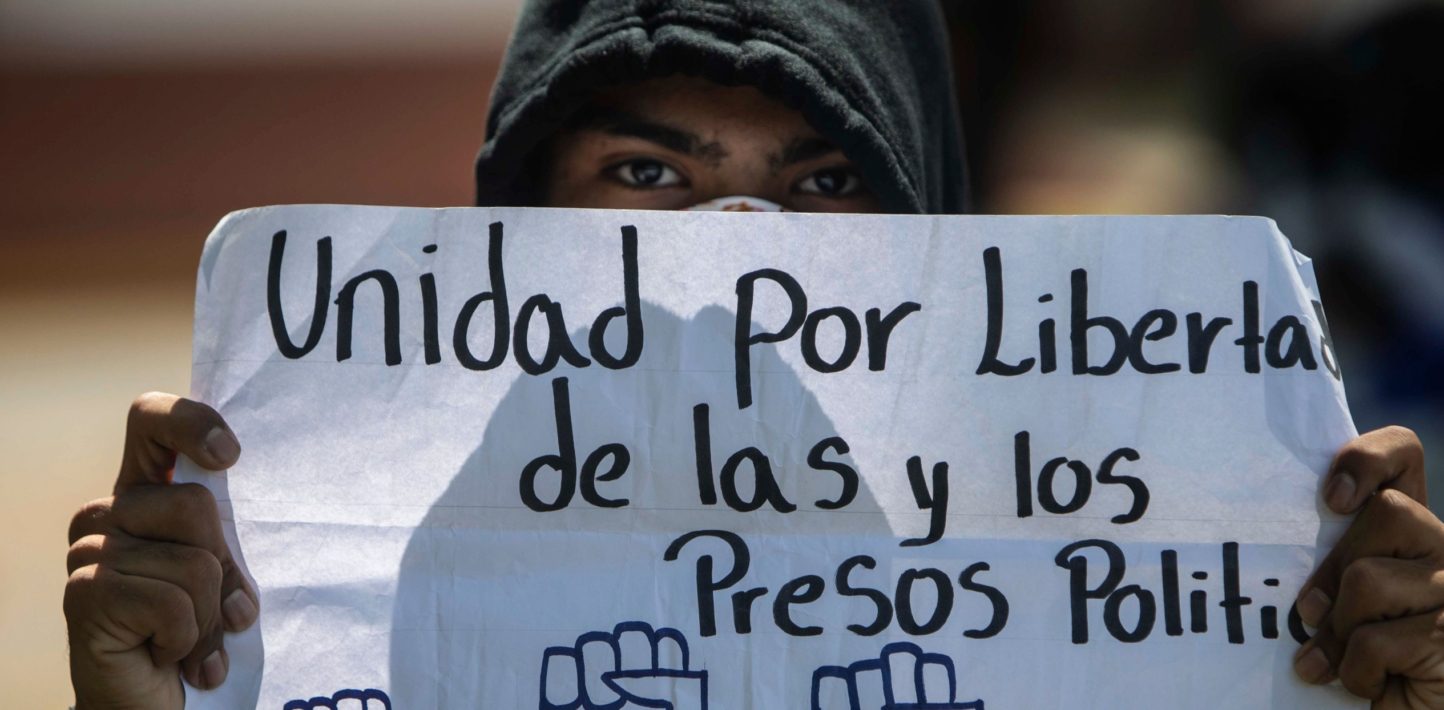

A combination of overcrowding, lack of safe drinking water and almost non-existent medical services has turned prisons in Nicaragua into coronavirus incubators. People languishing behind their crumbling walls, punished for expressing their ideas, report symptoms while the government of Daniel Ortega approves selective releases and downplays the scale of the pandemic.

“They’ve taken the guys.”

The message that lit up on the screen of Annabeth’s* mobile phone confirmed her deepest fears.

The Nicaraguan police had arrested Jhon, her partner, and two of his friends near the university where they studied in the country’s capital, Managua. It was 28 February 2020. Several days later, the young engineering student was brought before a judge accused of drug trafficking.

His lawyer says the process was plagued with irregularities, including to the fact that the evidence the defence tried to include was not taken into account. Jhon was sentenced to 12 years in prison, a sentence he is currently serving in one of the country’s biggest jails.

Jhon had been a target of the Daniel Ortega government for some time. Together with thousands of other students, he actively participated in the mass protests that began in 2018 – in which at least 328 people died (the majority at the hands of state agents and members of pro-government armed groups), thousands were injured and hundreds were arbitrarily detained.

And then came the coronavirus.

While the Ortega administration downplays the impact of the pandemic, those detained throughout the country report overcrowding, a lack of water and medical care, prisoners with symptoms and even fatalities. For those detained due to political motives the situation is even worse, with harsher punishments and discriminatory treatment. Their families say the virus is equivalent to a second sentence and they fear for their future.

Virus incubators

The Jorge Navarro prison complex, known as “La Modelo”, the largest and one of the oldest penitentiaries in Nicaragua, is one of the main destinations for those detained and punished for reporting human rights violations in the country. It was built in the late 1950s, around 20 kilometres from Managua.

In 2014, the government opened an annex building, commonly known as “La 300”, with maximum-security cells. At the time, the authorities confirmed that this area would be reserved for particularly dangerous prisoners. In practice, it is also used as a place to punish those who speak out or are considered opponents of the government. Staff who worked in the prison confirmed that the lack of security cameras in some areas facilitates the torture and ill-treatment of prisoners.

“La Modelo” has a total capacity for 2,400 people but in 2013 already housed almost double that, around 4,600, according to a report by the Nicaraguan Centre for Human Rights (CENIDH). Since then, according to CENIDH, the government has not published data and since 2010 it has not allowed the organization to visit the prison facilities. Local experts and lawyers who work with those detained say that the situation has worsened in recent years.

Nicaragua has one of the worst rates of prison overcrowding in Latin America, according to an analysis by World Prison Brief. The detention conditions are also among the worst in the region.

Jhon Christopher Cerna Zúniga is experiencing the unfolding of the COVID-19 pandemic like someone watching a tsunami from the front line.

He shares a square five-metre by five-metre cell with 22 other people. He says that to sleep they arrange a few mats on the floor and make improvised hammocks with sheets. There is not enough space for everyone. They sleep, eat, and spend every minute of the day in that space, other than the 60 minutes that they are allowed to go out to a patio for fresh air every two weeks.

The cell is very dirty, there are a lot of insects. They are very exposed to a constant risk of dengue fever

Annabeth*

The prison gives them two small food rations per day, and those who have the means supplement this with what their loved ones bring them in the two family visits and two conjugal visits that they are allowed each month, or the packages that they leave for them in the weeks in between. In practice, many families lack the means to pay for the journeys.

Water is provided in a bucket that each person has for washing, cooking, and drinking. The prison does not have safe drinking water, but Jhon has now learned to purify it with chlorine.

“On Sundays they make them wash the cells using that same water,” explains Annabeth, who visits him regularly. “The cell is very dirty, there are a lot of insects. They are very exposed to a constant risk of dengue fever.”

When Jhon was arrested at the end of February, hardly anyone was talking about COVID-19, even outside of Nicaragua. What they had been talking about for some time was the harassment and persecution faced by student leaders and activists who had participated in the protests in April 2018 which had led to Nicaragua making headlines around the world.

This is why something sounded strange when a judge accused Jhon of drug trafficking. The Public Prosecutor’s office alleged that the two police officers that arrested him found almost 1,300 grams of marijuana and 44 grams of cocaine in his backpack and demanded that he face 15 years in prison. He was finally sentenced to 12 years in prison and a fine.

His lawyer, Elton Ortega Zúñiga, who represents persecuted social activists, confirms that the charge is a typical strategy used against political opponents of the government.

“In 2018 the majority of politically motivated prisoners were charged with complex crimes such as organized crime and terrorism and they were imprisoned all together in the cell blocks,” he says. “But the government, like the virus, has evolved. They now accuse the opposition of common crimes such as armed robbery, possession, and drug trafficking. The authorities imprison them separately from each other and together with regular prisoners to stop them from organizing.”

Love vs. COVID-19

Daniel Ortega, who took office as president of Nicaragua most recently in 2017, likes to go against the tide. The fight against the COVID-19 pandemic is no exception.

While in March the World Health Organization recommended public information campaigns and social distancing among its measures of protection against the virus, the government encouraged mass meetings, denying that the virus was spreading throughout the country. Schools remained open, sporting events and public meetings were encouraged and supported – including a mass walk called “Love in the time of COVID-19”.

When the government published its strategy to fight the pandemic in May, critics said that the official record of cases did not represent reality. While Ortega reported that by 21 July there were 91 documented deaths caused by COVID-19 and 2,182 cases of infection, the Citizen Observatory, an independent group that collects reports from health professionals throughout the country mentioned in its weekly report that by 15 July there were more than 8,500 suspected cases and 2,397 deaths.

For the Pan American Health Organization, the official information is not sufficient to allow an adequate evaluation of the situation and it has requested a visit to the country to document the incidence of the virus.

Two types of prisoners

While Ortega attempted to downplay the impact of the pandemic, health professionals around the country reported the increase in deaths due to “respiratory causes” of people who were not tested for COVID-19, and reports emerged of funerals held in secret. The authorities dismissed health workers who spoke out and demanded that more serious measures be taken to address the pandemic.

Prisons, where overcrowding made any social distancing measures impossible, and with a lack of other hygiene measures, became potential incubators for the virus.

Between April and May, the Nicaraguan government ordered the release of 4,515 people, including older adults and those with chronic illnesses. In addition, 1,605 people were released from nine prisons in mid-July.

But Jhon, who suffers from a lung condition, epilepsy and a dislocated shoulder caused by the ill-treatment he received during a protest that was never treated, was not one of them.

Nor did the more than 80 people currently behind bars for exercising their rights make the list. It was not until 14 and 15 July that the authorities announced the release of four of them, according to reports from local media and organizations, although no explanations were provided.

“In Nicaragua there are two types of prisoners: political prisoners and regular prisoners. The government is playing politics with imprisoned people,” says the lawyer Ortega Zúñiga.

Families of imprisoned activists say that they receive different treatment when they attend visits. They have to wait for hours, sometimes their loved ones do not receive the medicines and cleaning products they send, and sometimes the guards take photos of them and do not give them privacy to talk during the visits.

Within the walls of “La Modelo”, coughing and moaning became signs of something terrifying. As of the end of March, rumours of prisoners with symptoms consistent with coronavirus spread inside and outside of the prison walls. Fever, cough, body aches. Prisoners taken to other cells. People “transferred” and never returned. Lawyers say that many report symptoms.

In Nicaragua there are two types of prisoners: political prisoners and regular prisoners. The government is playing politics with imprisoned people

Elton Ortega Zúñiga

“Maybe he died,” Jhon said to his lawyer when he told him that the guards had taken away an older man who was detained in a cell beside him and he had never returned. The man who cut his hair.

COVID-19 testing does not exist inside the prisons, Jhon told Annabeth during one of the visits. Not even for those who show symptoms, like him. He still feels the effects of a respiratory crisis that he had in April and that he said he did not receive treatment for.

“Each visit is more and more worrying,” says Annabeth. “I’m worried that he will get ill and they won’t tell me, I’m worried about the issue of hygiene, the lack of space, the food rationing and the lack of medical attention, which he has not received although we have requested it.”

Alexandra Salazar, a member of the Legal Defense Unit, explains that the pandemic has exacerbated the problems that the Nicaraguan prison system has been suffering from for years, particularly in terms of prisoners’ access to medical care.

“If they complain, they’re told that their conditions are psychological. The explanation of the prison system is that this (COVID-19) is a common cold,” she says.

Without medical care, the only alternative that the prisoners have is to care for each other with medicine that they manage to obtain from their families.

One of the members of Jhon’s family, who spoke anonymously for fear of reprisals, explained that he hardly has the money to buy basic medicines that Jhon shares with other prisoners. He says that when the prisoners complain, the guards limit the products that are allowed in.

For some of those in prison the situation is even worse.

Kevin Solís was arrested on 6 February by individuals dressed as civilians following a protest near the Central American University in Managua where he studied.

One week later he was transferred to the “La Modelo” prison. Shortly after, following a trial that, according to his lawyer, was plagued with irregularities, he was sentenced to four and a half years in prison, accused of having stolen around 600 Córdobas (17 USD) from a man who was walking near the university.

His lawyer, Aura Alarcón, says his case follows the same pattern as Jhon’s: silencing activists by charging them with common crimes.

Kevin was one of the public faces of the student protests that began in 2018. In September of that year he was arrested during one of the protests and he was released in April 2019.

Alarcón says that in the most recent trial they were not allowed to present video evidence that, she claims, proved that Kevin was innocent. The young man reported that, during his detention, he was the victim of a myriad of ill-treatment during interrogation sessions, including beatings and insults.

“Kevin is being criminalized for being a student leader. They are all being charged with serious common crimes, leaving them without credibility and for which there is no possibility of getting released,” explains Alarcón.

Two months after being sent to La Modelo, Kevin was transferred to a three-metre by two-metre punishment cell in “La 300”. He is still there. No one provided a clear explanation for the reasons for this change.

The reports of guards and prisoners with symptoms, even in the maximum-security area, were revealed to Alarcón, who says that despite the ill-treatment that Kevin has suffered from, he has not received any type of medical attention since February.

“I only managed to see his face through a window,” she says of the last time that she visited him, at the end of June. “He began to cry, saying that he couldn’t stand being there anymore, that he was going crazy. He told me they interrogated him, he showed me that there was a camera recording us. He told me they tortured him psychologically and that they beat him.”

In an effort to increase medical care for those in the prisons, the prisoners’ family members now know which questions to ask their loved ones during visits. With that information, they consult healthcare workers about the type of medicines that they can take them and measures such as distancing, hand washing and cleanliness.

If they complain, they’re told that their conditions are psychological. The explanation of the prison system is that this (COVID-19) is a common cold

Alexandra Salazar, a member of the Legal Defense Unit

Many are impossible to put into practice. “La Modelo” does not have clean water; the prisoners who do not have access to family members are forced to drink the water that is available.

A person needs to consume approximately two litres of water per day, although they need access to at least seven litres for cooking and hygiene needs, according to the World Health Organization. The consumption of non-potable water, in addition to the lack of treatment of symptoms of coronavirus, can cause health problems in the short and long term.

“When you don’t know a person’s temperature and they are not treated, physiologically it can have direct consequences,” explains Doctor Freddy Blandón, who was the Head of Medical Services for Maximum Security at “La 300” in 2017 and is now part of a civil society organization that supports victims of state repression.

“It can cause meningitis and problems in the brain. The loss of taste and smell, caused by inflammation of the nasal mucous membrane can be reversed by the use of corticosteroids and antihistamines, but if you do not have them it can persist over time and cause permanent alterations.”

Erika Guevara-Rosas, Americas director at Amnesty International, says Ortega’s government is playing with the lives of those who are detained. “Nicaragua is facing a question of life or death. We are not only talking about freedom, but the lives of dozens of people who were put behind bars in order to silence them. The question is: How far is Daniel Ortega willing to go to keep them in silence?”

The lawyers of those detained are making a series of requests to the authorities, including that alternative measures be implemented in order to guarantee the safety of those in prison. Human rights organizations, including Amnesty International, have called for the release of all those who have been detained solely for exercising their rights.

“We’re asking for house arrest, at least during the period of highest risk of the virus, but it’s very unlikely that they grant it,” says Ortega Zúñiga of Jhon’s case. “If they don’t want to put those on the outside in quarantine as a preventative measure, then even less so for those in prison. It would mean admitting that coronavirus is more than a political enemy in Nicaragua.”

*Name changed for security reasons.