Flor de Maria Paraná was losing hope. The pollution of the Marañón River had irrevocably changed life in Cuninico, her community in the Peruvian Amazon. So she took a half-litre soda bottle and filled it with water contaminated with oil and took it to a hearing before the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (IACHR) in Chile.

Named an “Indigenous Mother” by the Kukuma people of Cuninico, Flor had already participated in various forums and had even testified before the national Congress. But it always seemed to her that her audiences failed to understand her, or that they would listen for a while and soon forgot what they heard. This time would be different.

“I listened silently to how they denied the pollution,” says Flor of the testimony given by lawyers for Petroperu, the state-owned company operating the pipeline that had a serious rupture in 2014.

“Now they’ll see it up close,” she thought, before displaying the evidence she had brought. “I brought you a bottle of water polluted with oil,” she said, “so that you’ll believe me.”

The river has a special significance to the Kukuma people. Because they have historically lived on riverbanks, their lives, myths, spirituality and philosophy are tied to water. The Marañón provides fish for Cuninico year-round. During the rainy season, the river rises and invades the community’s streets, and in the summer when it retreats it leaves nutrients in their fields.

Local communities also drink and cook with the water from the river, after filtering or boiling it. The river also provides recreation. When temperatures reach 36 degrees, boys and girls leap into the water, splashing and playing ball games.

I brought you a bottle of water polluted with oil, so that you’ll believe me

Flor de Maria Paraná

But in 2014, after 2,358 gallons of oil spilled into the river, locals could no longer enter the water. The Marañón was left contaminated with high levels of toxic metals.

When Flor realized that oil had spilled into the river, she felt a sharp pain in her chest. She had taken her young son, José Manuel, to bathe at a bend in the river where she always fished with her husband. “That water contaminated with oil, that’s what I poured over him,” she said. Her son started to get sick and developed rashes.

Flor was worried, but she took action. She went to talk to her neighbors and inform them about the situation. She called them to meetings and told them about the dead fish and the dangers of the spill. Most had seen that the insides of the fish they gutted for their meals were burned. They listened to her and took precautions. This health and environmental emergency alarmed them all.

Flor’s work has always been as an educator. When she was 18 she worked with the Catholic Church of Santa Rita, an hour from Cuninico. This is how she learned about first aid, health, and prevention. When the news of oil spills and pollution reached her, she remained alert and read everything she could on the topic. “Then they named me ‘Indigenous Mother.’ I had to learn, to educate myself,” she says.

The framed certificate of Flor’s honorary title hangs in the entrance of her home. Beside it is a colorful painting of Amazonian flora and fauna, a gift from her other son, an artist who lives in Yuriaguas. Whenever she sees these gifts, she thinks of her childhood and her garden, just metres from the river.

Cuninico sits on the banks of one of Peru’s most magnificent rivers, but it doesn’t have access to clean water. In 2017, the government declared a health emergency in Cuninico and the surrounding area due to the contamination of fresh water sources. The people of Cuninico asked themselves, “And where will we get our water?”

“We collect rainwater in barrels to cook, to bathe, for everything,” Flor says. “That’s why we’re happy when it rains. But if the sky doesn’t darken, we don’t have water.”

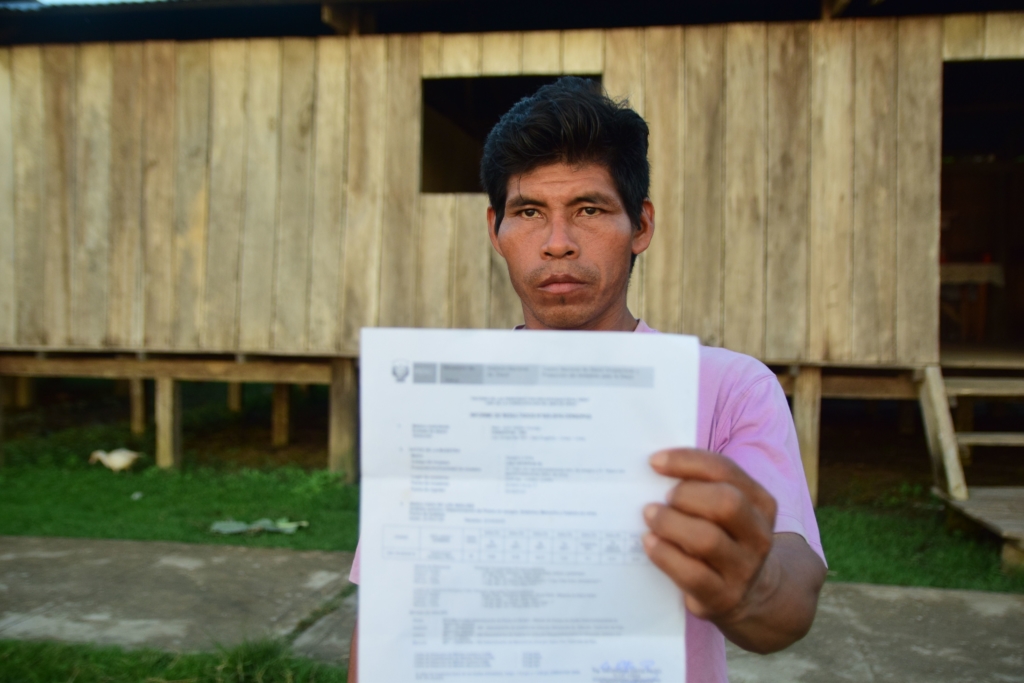

Although she doesn’t like to travel and has to do so carrying medicine and with her young son at her side, her fight for her community has taken her several times to Lima, where she has spoken with ministers, members of Congress, other government officials, NGOs, and journalists.

“I ask you to fight for Cuninico. This is what I ask, because we need healthcare, a doctor with expertise in heavy metals,” she says. “As a mother this worries me, because all [those affected] are like my own children.”

When the judges and officials at the IACHR hearing saw the bottle of contaminated water that Flor had brought from Cuninico, they were visibly shocked. The IACHR sided with Flor, issuing a precautionary measure in favor of Cuninico due to the Peruvian state’s failure to address the health concerns of the community. Remediation was urgently required.

As a result of the community’s activism, the government has installed a water purification tank. It gives the community water for two hours per day through a tube system between houses. The government is also building a purification plant nearby, but it will take months to complete. The government has also offered workshops on gardening and sewing machines.

I’d like everyone to support us. Not for me, but for Cuninico

Flor de Maria Paraná

Flor was surprised when Amnesty International activists arrived to deliver 3,000 letters with messages from people all over the country recognizing her work as a human rights defender. “This is all for me?” she asked in disbelief, even though her efforts had earned her renown. She began to laugh as she opened each of the envelopes and saw the crayon drawings and messages on colored paper. “Look how they’ve drawn me!” she exclaimed as she saw a child’s drawing of her with her husband and children.

Flor tries to pass on all her knowledge as best she can. Sometimes, because her path is a difficult one, she feels that she wants to return to her life as a Catholic Church aide. But she continues to courageously denounce the situation faced by the communities affected by the toxic pollution.

“I want us all to live in harmony. Before, we used plant medicine. We didn’t need all these other medicines,” she says. Love for her river, for her children and for her riverside home galvanize her struggle. “I’d like everyone to support us,” she concluded, “not for me, but for Cuninico.”