As Muhammadu Buhari – the newly elected president of Africa’s most populous, oil-rich country (pictured above, right) – prepares to take office, we look at 10 ways he can transform people’s lives. (Image: © AFP/Getty Images)

1. Investigate possible war crimes in north-eastern Nigeria.

Children, men and women live in constant fear of being murdered or abducted by the armed group Boko Haram, and of being arrested, detained, tortured and even executed by the military. These possible war crimes and crimes against humanity need urgent, independent investigation.

2. Protect people caught up in the conflict.

Boko Haram’s bloody assault and the military’s heavy-handed response has killed thousands and forced hundreds of thousands to flee. In January, Amnesty’s satellite images showed how the fighting had damaged or completely destroyed over 3,700 buildings in two towns – Baga and Doron Baga – alone.

3. Make torture a crime.

Amnesty’s Stop Torture campaign is exposing how Nigeria’s police and military routinely torture people, some as young as 12, including by beating, shooting and raping them. The new government can stamp out torture by criminalizing it and making sure anyone found responsible is tried and sentenced.

4. Scrap the “same sex marriage prohibition act”.

This outrageous law makes all relationships – except heterosexual ones – a criminal offence. People who speak out for gay rights also risk being locked up.

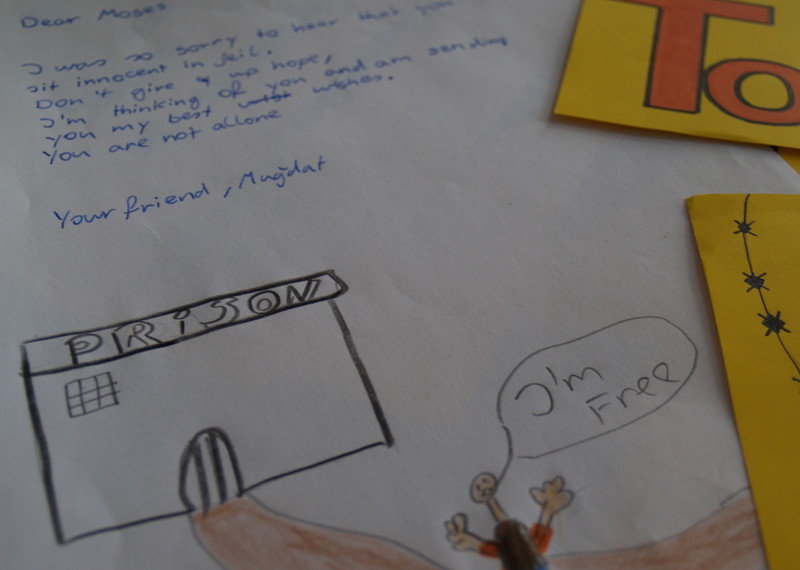

5. Get the justice system working for poorer people.

Nigeria’s criminal justice system is under-resourced and deeply corrupt. Most of the 55,000 people stuck in its overcrowded prisons can’t afford lawyers or bail, and most are still waiting to see a judge. Many are convicted after deeply unfair trials, and more than 1,000 are wasting away on death row.

6. Let lawyers and families visit people in detention.

People detained in police and military cells often aren’t allowed to see their lawyers or families. This lack of communication increases their risk of being tortured, killed or of simply disappearing.

7. Stop people suddenly being kicked out of their homes.

Hundreds of thousands of people live with the constant threat of being kicked out of their homes. By creating a law banning all forced evictions, the government could stop communities being destroyed and families from ending up on the street with no compensation and nowhere to go.

8. Don’t let oil companies get away with pollution.

Shell was recently forced to pay one Niger Delta community £55 million in compensation for two major oil spills. But it hasn’t cleaned up the pollution yet. By insisting that companies fix broken pipelines and clean up when accidents happen, the government can protect lives, jobs and the environment.

9. End all executions.

Nigeria executed four people in 2013, for the first time since 2006. Its new Terrorism Act has widened the use of the death penalty. It also sentences people who were children at the time of their crime to death, breaking international law. By changing direction and ending executions once and for all, it could set an important example to its neighbours.

10. Look after Nigeria’s children.

Many children in Nigeria are missing out on their education, forced to survive on the streets, and abused by the police or in prison. Others are abducted by Boko Haram or forced to become soldiers in the military. By protecting their right to a childhood, Nigeria will be investing in a safer, more peaceful future.

Nigeria: A quick guide

166,600,000 people (UN, 2012). Around half are aged under 18.

4,000Minimum number of people killed in attacks by Boko Haram during 2014.

52/53Life expectancy for men and women respectively.

70%Percentage of government revenue from oil and gas.

9 million orphans (UNICEF)

7.4%Percentage of babies that don’t survive their first year.

1 in 3Nigerians living in slums.

2 millionPeople forcibly evicted from their homes since 2000. Many are still homeless.

38,000People in prison with no conviction of any offence (seven out of every 10 prisoners).

Read more

A beginners’ guide to human rights in Nigeria

This article was originally published in the April-June 2015 issue of Wire, Amnesty’s global magazine.