After 10 years in jail, and over 800,000 messages from activists around the world, Moses’ life has been spared. Here, we speak to Justine Ijeomah, Director of the Human Rights, Social Development and Environmental Foundation (HURSDEF) in Nigeria and long-time ally in the campaign for Moses’ freedom. He describes Moses’ journey from schoolboy to death row inmate, and how the 26-year-old torture survivor reacted when he found out his life had been spared.

I promise to be a human rights activist, to fight for others.

Moses Akatugba, 28 May 2015

These were among the first words Moses uttered when Justine called him to break the news that Emmanuel Uduaghan, Governor of Nigeria’s Delta State, had issued him a last-minute pardon on 28 May 2015. Justine had spent the day anxiously monitoring the Governor’s Facebook page, hoping for updates. “That day, I was so tense: I knew it was the last day the Governor could pardon Moses before he left office” he explains. “Finally, the good news came.

I called Moses immediately and when I told him what had happened, he was overwhelmed with joy: he could not talk. It was a long time before he could respond, and then he just began to shout.

Justine Ijeomah

From schoolboy to torture survivor

Aged 16, Moses was a normal schoolboy from southern Nigeria. Full of hope for the future, he was relieved to have finished his secondary school exams and was waiting anxiously for his results. His dream was to fulfill his late father’s wishes and study medicine.

On 27 November 2005, Moses said goodbye to his family and left to visit his aunt. When he didn’t come home as planned, his mother became worried. A widow, she was supporting her five children by selling food at a local market in Effurun, a busy city in Delta state.

While his mother was looking for him, Moses was being interrogated by soldiers. If Moses had been allowed to call a lawyer – or even just his mother – it could have protected him from torture. But for the first 24 hours, nobody knew where he was.

A local street vendor eventually visited Moses’ mother, saying she had seen a group of soldiers arrest him. Moses wasn’t to come home for almost ten years.

‘Unimaginable pain’

It would be almost eight of those years before Justine was even to find out about Moses’ case. But as soon as he did, he went to Warri prison and interviewed him. “My organization [the Human Rights, Social Development and Environmental Foundation] in Nigeria documents cases of juveniles in prison with adults, so when I heard about Moses’ case it caught my attention” Justine explains.

There, Moses told Justine that when he was first arrested soldiers had shot him in one hand, beat him on the head and back, and taken him to a local army barracks for interrogation. They showed him a corpse and asked him to identify it.

“When Moses said he didn’t know the dead man, the soldiers beat him again.” Justine remembers. “They then took him to a police station, where he says the officers beat him hard with machetes and batons. They tied him up and left him hanging upside down from a ceiling fan for hours. They also pulled out his toe and finger nails with pliers.

The pain I went through was unimaginable. In my whole life, I have never been subjected to such inhuman treatment.

Moses Akatugba

The police suspected Moses of stealing three phones, some money and vouchers in an armed robbery. He has always denied these charges. But the officers tortured him and forced him to sign two pre-written “confessions”, which were later used as evidence during his trial.

From the classroom to death row

After eight years in prison, on 12 November 2013, Moses was sentenced to death by hanging. The conviction was based on his “confession” and the alleged robbery victim’s testimony. The police officer who investigated his case didn’t turn up in court.

Because Moses was a child when he was arrested, he should never have been sentenced to death. It is illegal under international law. Also, any “confession” obtained after torture should not be allowed as evidence in court.

Youth outrage around the world

It was around this time that Justine approached Amnesty to join the campaign. “I began to travel to many different countries, telling Amnesty members Moses’ story and encouraging them to join the campaign” Justine explains. “I was so impressed by the level of commitment they had, especially the youth activists, who would go and demonstrate at the Nigerian embassies. I said to myself, if these children are this passionate about Moses, I should also go the extra mile. And so I started to lobby all of the agencies that could release him.”

I was so impressed by the commitment of the youth activists who would go and demonstrate at the Nigerian embassies. I said to myself, if these children are this passionate about Moses, I should also go the extra mile.

Justine Ijeomah

“We also took the campaign to Moses’ prison, and shared materials from Amnesty’s Stop Torture campaign with the death row inmates. After that visit, many death row inmates spoke out about torture. It was horrifying to hear their stories; many of them only confessed because they were tortured.”

A new start

Moses has spent much of the last ten years isolated and traumatized. After he was transferred to a new prison in 2006, he was only able to see his family twice a month. “I never thought I’d be alive until today,” he told us only recently.

He thought his dream of becoming a doctor had been destroyed. Not long ago he told us that what pained him most is that while he’s been in prison, many of his former classmates have gone to university and found good jobs.

On 28 May 2015, I was so tense. I knew it was the last day the Governor could pardon Moses before he left office.

Justine Ijeomah

But it all changed in the last few weeks, as local activists worked hard on the ground and thousands of Amnesty members sent tweets, messages, Facebook posts and signatures to Governor Uduaghan – in his last weeks in office. “We really lobbied the authorities for Moses” Justine explains. “I sent text messages to those involved; spoke to them; I called the Governor five times, but he did not pick up the phone. But finally, the good news came.”

Today, after nearly ten years in prison, Moses is finally free. He can finally return home to begin his life again, perhaps as a doctor, and certainly as a human rights activist.

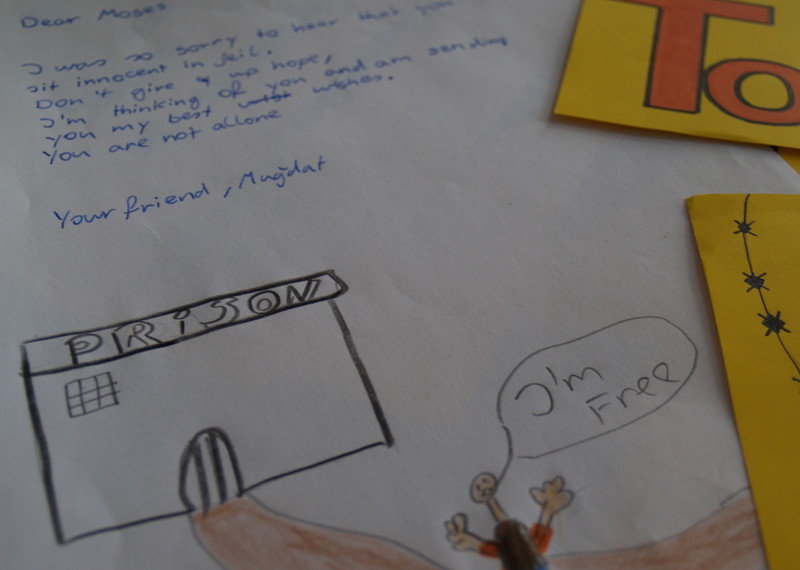

Amnesty International members and activists are my heroes. I am grateful also to members and volunteers of HURSDEF for their support. I want to assure them that this great effort they have shown to me will not be in vain, by the special grace of God I will live up to their expectation. I promise to be a human rights activist – to fight for others.

Moses Akatugba