Executive Summary

In January 2024, Al-Jazeera published an investigation that documented how people had lost access to crucial social protection schemes in the state of Telangana, India, after the introduction of Samagra Vedika, a digitalized system for welfare delivery being used by the Government of Telangana.The system is deployed by the state government to collate data on individuals from multiple sources to assess their eligibility for social security schemes. This data, for example on assets such as car ownership, was reportedly erroneously attributed to individuals, leading to them no longer being eligible for the social assistance scheme. For Amnesty International, the Al-Jazeera reports raised significant human rights concerns around people’s rights to social security, privacy, redress and remedy, equality and non-discrimination. Accordingly, Amnesty International set out to investigate the Samagra Vedika system further through a technical investigation.

This technical explainer provides a brief background on digitised welfare technologies and the risks to human rights they can introduce. It then goes on to discuss the specific technology, known as Entity Resolution, which is provided to the Government of Telangana by Posidex Technologies Private Limited, that underpins the Samagra Vedika system. In particular, this explainer discusses how Entity Resolution represents a new type of digitalized welfare technology and why its technical design and deployment raises human rights concerns for Amnesty International, and why greater transparency and access is imperative. Finally, it documents Amnesty International’s attempt to conduct a technical investigation ( “algorithmic audit”) of the underlying Entity Resolution software. The audit ultimately couldn’t be completed due to hurdles faced in procuring access to the software, however the study still provided valuable information and lessons for Amnesty International and other researchers in the algorithmic accountability space.

This technical explainer is part of Amnesty International’s broader research on the uses of automated or algorithmic technologies in the public sector and their implications on human rights. Whilst the research focuses on the Samagra Vedika system, with the growing appetite for data linkage and digitalised welfare technologies, the findings and implications of this research are applicable globally. It builds on the advocacy, campaigns, research, and strategic litigation work that Amnesty International has undertaken in the field of social protection and of digital technologies.

Glossary

- Artificial Intelligence (AI) – Broadly speaking, AI is any technique or system that allows computers to mimic human reasoning.

- Machine Learning (ML) – A sub-set field of Artificial Intelligence. A technique to provide AI with the capacity to learn from data to perform a task (either specific or general), and when deployed, ingest new data and change itself over time.

- Deep Learning – A sub-set field of Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning. A type of ML characterized by (1) the use of artificial neural networks (a type of algorithm that attempts to mimic human reasoning) and (2) having the ability to digest and learn from vast amounts of data. It is commonly used for tasks like image and voice recognition tools.

- Algorithm – An algorithm is a list of mathematical rules which solve a problem. The rules must be in the right order – think of a recipe. Algorithms are the building blocks of Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning. They enable AI and ML technologies to train on data that already exists about a problem so that they are able to solve problems when working with new data.

- Algorithmic decision-making system – An algorithmic system that is used in (support of) various steps of decision-making processes.

- Automated decision-making system – An algorithmic decision-making system where no human is involved in the decision-making process. The decision is taken solely by the system.

- Semi-automated decision-making system – An algorithmic decision-making system where a human is involved in the decision-making process, or the algorithm is used as decision support. Often these systems are used to select cases for human review or to assist in the decision-making process by providing information and/or suggested outcomes.

- Black-box algorithm – An algorithmic system where the inputs and outputs can be viewed, but the internal workings are unknown to its designer. This terminology most readily applies to more complex ML algorithms.

- Accuracy – In the field of AI, accuracy measures are generally used to ascertain the number of ‘correct’ outputs that a system produces whether those outputs are predictions, identifications or simpler calculations (as a percentage of the number of total outputs made).

- Explainability – Designing an AI system such that a human is able to understand and explain the way the model works (counter to the idea of a black-box system) and retain oversight over its functioning. Explainability is a nascent field and there are also other similar approaches which aim to increase transparency into how an AI system is functioning, such as ‘interpretability’.

- Profiling – In the GDPR, profiling is described as the automated processing of personal data to evaluate personal aspects of a person such as their performance at work, economic situation, health, personal preferences or interests, behaviour, location movement

- Fairness – There are numerous suggested methods, approaches and definitions for embedding fairness into AI systems in order to avoid algorithmic bias. They are all predicated on the idea of eliminating from the output of an AI system any prejudice, discrimination or preference for certain individuals or groups based on a characteristic. Though fairness methods are an important element of debiasing AI systems, we generally consider them a limited tool in and of themselves.

- Supervised learning – In supervised learning, AI is trained from examples consisting of inputs and labelled outputs. The system learns to find patterns and relationships between the inputs and labelled outputs, and the developer has a specific objective or target for the system to predict or categorise. In this way, the AI system starts to make its own predictions on any new inputs (without corresponding labelled output), based on the historical associations between inputs and labelled outputs identified in the training data.

- Unsupervised learning – In unsupervised learning, AI systems discover patterns or relationships in unlabelled data, humans do not actively ‘indicate’ to the AI system the target or output of the exercise

- Self-learning algorithm – Self-learning algorithms give algorithmic systems the ability to independently and autonomously learn over time, and to make changes to how they work without these changes being explicitly programmed by humans.

- Predictive algorithms – The use of AI techniques to make future predictions about a person, event or any other outcome.

- Classification – Classification is a supervised machine learning method where the model tries to predict the correct label of a given input data, amongst a known finite set of labels. In classification, the model is fully trained using the training data, and then it is evaluated on test data before being used to perform prediction on new data.

- Clustering – Clustering is an unsupervised machine learning technique for identifying and grouping related data points in large datasets without concern for the specific outcome. It does grouping a collection of objects in such a way that objects in the same category, called a cluster, are in some sense more similar to each other than objects in other groups.

- Proxy Means-testing – Proxy means tests are a form of poverty targeting where eligibility for social protection schemes is determined based on household characteristics being used as proxies for wealth, such as household composition, type of housing, existence of goods such as radio, television or refrigerators, productive assets such as farmland or cattle, or level of education of household members. Households are then ranked or allocated scores based on this data, and of these, qualifying households are considered eligible for assistance.

- Social Registries – Social Registries are information systems that support the process of outreach, registration, and assessment of needs to determine the potential eligibility of individuals and households for one or more social programmes.

- Social Protection – Social protection refers to a broader range of contributory (those financed through contributions made by an individual or on their behalf) and non-contributory (those that are funded through national tax systems) programmes. Social protection programs can include (I) social insurance, such as pension insurance; (ii) employment and labour programs, including skills training, unemployment benefits, and job search assistance; and (iii) social assistance and cash benefits for people living in poverty.

Introduction

Digitalisation and the use of algorithmic systems to deliver essential public services is a growing trend, and in many countries, governments have been increasingly turning to digital ‘solutions’ to deliver social protection schemes1. This can include the introduction of Digital and/or biometric Identifiers, social registries, algorithms and automated or semi-automated decision-making systems. Whilst this trend is often presented by governments as a neutral or technocratic solution to achieve greater coverage, streamline administrative systems, and ensure welfare is reaching those who need it most, there has been significant research to show that digitization of social protection poses many risks to human rights and can exacerbate inequality. The former UN Special Rapporteur on Extreme Poverty and Human Rights, Phillip Alston stated that “systems of social protection and assistance are increasingly driven by digital data and technologies that are used to automate, predict, identify, surveil, detect, target and punish”.

In the past 10 years, the increased austerity measures being adopted by many countries globally, has put pressure on government agencies to optimise resource allocation and make efficiency gains. In parallel, politicised narratives that welfare fraud is out of control has pushed states to look for new ways to identify cases of fraud and error, and with both the increase in the volume of data and the technologies available to public sector agencies, states have started incorporating more elaborate Artificial Intelligence (AI), specifically Machine-Learning (ML), algorithmic solutions to complete such tasks.

These technologies require large-scale and interoperable administrative datasets to build a full data-based profile of welfare beneficiaries. This profile can then be used to make an assessment of whether they’re eligible for the scheme in question, or a prediction as to how likely a beneficiary may be of committing fraud. Linking personal data together in such a way is a complex technical task due to inconsistent and non-standardised data collection practices across public sector agencies.

As a result, states can turn to “Entity Resolution”, a technique to identify data records in a single data source or across multiple data sources that refer to the same real-world entity and to link the records together. In other words, Entity Resolution attempts to connect the dots between different databases where the same person’s name and other personal information that is used to link the databases is recorded inconsistently.

Entity Resolution is at the heart of welfare administration in India’s Telangana state, which increasingly relies upon an algorithmic system called Samagra Vedika, to identify and classify welfare beneficiaries across various government schemes. A recent investigation published by Al-Jazeera in partnership with the Pulitzer Center’s Artificial Intelligence (AI) Accountability Network has revealed a pattern in how the flawed implementation of this algorithmic system denies families access to welfare in an arbitrary and unaccountable manner. The investigation collected testimonial evidence from dozens of impacted individuals and communities, and triangulated this with documentation and other materials collected via Right to Information requests submitted to public sector agencies.

In the field of AI accountability, there is an increasing move to complement such evidence with an “algorithmic audit”– a technical research methodology which aims to assess and report the systems’ performance and impact. Audits allow us to overcome some of the issues of opacity in algorithmic systems. Such opacity hinders accountability and public scrutiny, leading to cases where they violate people’s right to privacy, non-discrimination, social security, and redress and remedy. Over the past year, Amnesty International has been auditing the Samagra Vedika system using various technical research methods. This technical explainer unpicks the technologies that underpin the Samagra Vedika system from the evidence gathered in the process, and discusses the implications of these in respect to the system’s impact on human rights. Ultimately, while challenges in accessing the system to study its workings prevented a full audit from taking place, this technical explainer summarises the methodological approach Amnesty International took to studying Samagra Vedika. Through this technical explainer, Amnesty International hopes to add to the algorithmic harms evidence base available to civil society, and to share methodological learnings civil society and journalists encounter when conducting such research.

Samagra Vedika and access to social protection in India

In 2019, the Government of India’s Economic Survey lauded a small state government programme in Telangana2. This programme, called Samagra Vedika, would integrate a number of disaggregated datasets from various government departments in order to provide a “360-Degree view” of the people in those datasets – their families, their criminal history, their expenditures, electricity consumption, among others. This integrated data would then be sorted and analysed through complex computational algorithms, often branded as ‘Big Data’ and ‘Machine Learning’ systems, to make decisions about how government welfare schemes should be administered – namely, who should get what, how much, and when.

Using digital technologies and ‘data-based solutions’ is not a novelty in social security administration in India. Indeed, even as governments introduce new family ID schemes and complex algorithmic systems in welfare, in their effort to project a techno-solutionist vision of ‘Digital India’, similar experiments in welfare administration have already caused massive harm to populations who are already vulnerable to marginalisation and deprivation. India’s ‘Aadhaar’ biometric ID system, for example, has been criticised for the exclusions it has caused in welfare administration, and also the risks it poses to the constitutional right to privacy.

Samagra Vedika is now a regular part of administration of social protection schemes in Telangana – used to identify alleged ‘duplicates’ in government welfare schemes, to test the eligibility of recipients of schemes against measures like income or wealth, and to identify ‘fraud’ conducted by welfare recipients. The model is also being replicated by governments around the country – through Haryana’s Parivaar Pehchan Patra; Tamil Nadu’s Makkal ID; Jammu and Kashmir’s Family ID; Karnataka’s Kutumba, among others. These schemes, and the technologies that underpin them, are now responsible for the administration of social security – pension schemes, subsidized food schemes, housing schemes, agricultural loans – for millions of people in India who rely on government assistance.

These projects aim to create a databased system, or ‘social registries’, which are information systems that support the process of outreach, registration, and assessment of needs to determine the potential eligibility of individuals and households for one or more social programmes. Social registry based systems have been shown to pose significant risks to human rights when they have been deployed in Serbia and Jordan. For example, the Social Card system in Serbia was opaque, rolled out without adequate safeguards or human rights protections, and was shown to widen existing discrimination and created additional barriers for people to access their right to social security.

The right to social security

The right to social security is recognized and protected by international human rights law. Article 9 of the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR) and Article 22 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) recognize the right of everyone to social security.5 According to ICESCR, states are responsible for ensuring that social support is adequate in amount and duration so that everyone can realize their rights to family protection and assistance, an adequate standard of living and adequate access to healthcare. The UN Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (CESCR) has recognized that the right to social security is “of central importance in guaranteeing human dignity” and is an essential precondition of the right to an adequate standard of living and other rights, including the right to adequate food. States have an obligation to ensure the satisfaction of “minimum essential levels of benefits to all individuals”.

The technology underpinning Samagra Vedika adds an additional layer of opacity and therefore represents a new class of digitalised welfare technology. Whilst, it draws parallels with systems deployed in Serbia and Jordan in that its purpose is to use social registries to proxy-means test social security applicants, its design diverges from these systems as it uses machine-learning approaches to create the social registry. In the case of Serbia and Jordan, this additional layer of technology was not present.

Once siloed databases and records are integrated, this information can be used for a number of purposes. In many cases, the systems are used to identify whether a record has been ‘duplicated’ in the database, and if so, it seeks to automatically ‘deduplicate’ or remove this record. In other cases, the systems can be used to match information according to specific rules and thresholds, and automatically create a profile of an eligible or ineligible beneficiary. For example, the integration of pension schemes with birth and death registers can be used to determine if a deceased person appears in a pension schemes list. Finally, the same system can be used to rank beneficiaries based on a system of income and wealth profiling known as ‘proxy means testing’, whereby different information (for example, electricity consumption or vehicle ownership) can be used to classify whether a household is more, or less, eligible for means tested social security schemes. The deletions, inclusions and classifications or rankings produced by the system are then used as the basis for making decisions about welfare entitlements.

The reports published in Al Jazeera indicate that the algorithms at the core of these systems are making social security more opaque, unaccountable, and error-prone. The investigations show how these systems have been operating to exclude large numbers of people who are and have been reliant on government schemes for housing, food and pension. Errors in the system caused by incorrect data, or incorrect analysis by algorithmic systems, are leaving people in the lurch, automatically disabling their entitlements, with little access to formal recourse. According to the investigations published in Al Jazeera, the exclusions involving these systems could range from tens of thousands to even millions of people being excluded from welfare at the press of a button, particularly impacting vulnerable and poor communities who are reliant on social security.

This highlights the need for greater transparency. However the system is externally procured from Posidex Technologies, meaning the underlying technology is proprietary, which public agencies have used as an excuse to exempt disclosures under the Right to Information Act provisions3. Due to this opacity, this technical explainer can present only a partial view of the system. The precise nature of the system’s inner workings remain unknown.

Amnesty International wrote to Posidex Technologies Private Limited in advance of the publication of this technical explainer, summarising our findings and highlighting the human rights risks of the Samagra Vedika system. At the time of publication of this explainer, we have not received a response.

Entity Resolution as a new class of digitalized welfare technology

Entity Resolution is the task of finding records that refer to the same real-world entity (e.g. a person, a household) across different data sources. In practice, it involves selecting and comparing pairs of records to determine whether they are a match or not. It can be further divided into the subcategories of “Record Linkage” and “Deduplication”. Record Linkage focuses on finding similar records in two or more datasets, while Deduplication aims to identify matches within a single dataset.

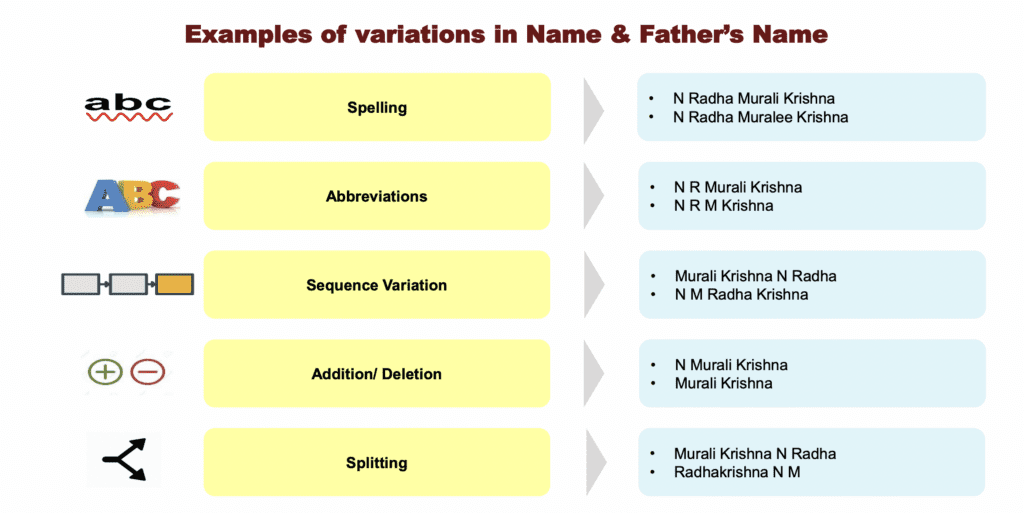

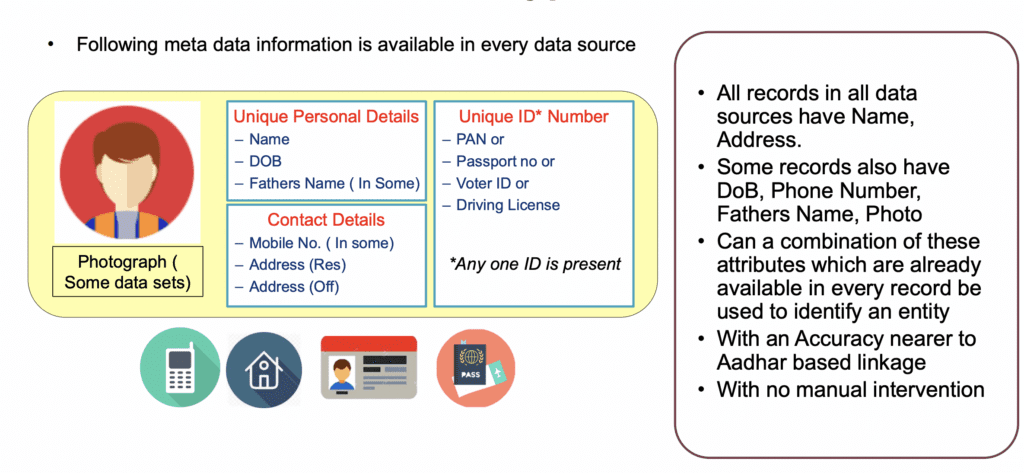

Entity resolution is becoming common practice within domains such as healthcare and finance, where private or public sector actors wish to collate as much information on individuals as possible, however there is not necessarily a common identifier to merge databases together. Within the context of Samagra Vedika, the government wishes to create a “consolidated view”, whereby they can link administratively collected databases including older age pensions, houses and land databases, electricity and water connection, ration cards, vehicles. The common identifiers across these databases include name, address and date of birth, however there is large variation in how these may be collected and recorded, meaning simpler “rules-based” (deterministic) matching will not be effective. Rules-based matching relies upon the identifier (e.g. name) being spelt and digitally stored in the exact same way across two databases.

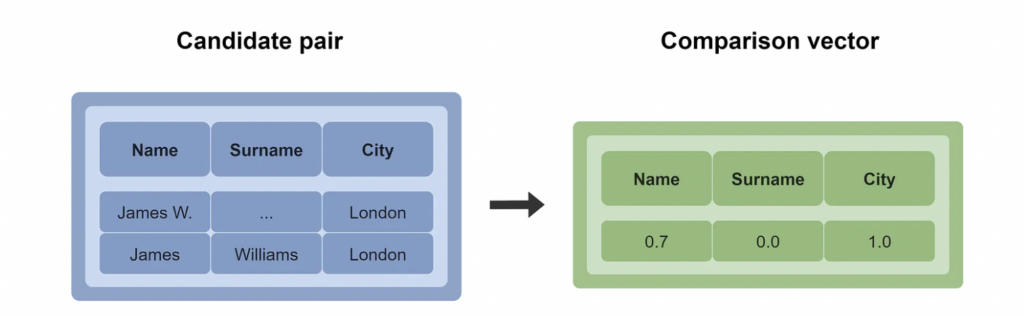

Entity Resolution attempts to resolve this issue by training an algorithm to systematically compare pairs of records based on a set of common identifiers, and designate a score of how likely they are to be the same person. The process can be complex and is often computationally intensive when applied to large datasets as it requires millions of records to be compared to one another. The algorithmic pipeline is split into three phases:

- Preprocessing and Blocking, this stage attempts to reduce the computational time taken to compare records by cleaning the data, immediately discarding pairs which are definitively not matches, and grouping together records that are likely to be similar based on set criteria– therefore narrowing the total number of comparisons that need to be made.

- Comparison and Matching, this stage focuses on computing the similarity between the pairs of records. A variety of supervised or unsupervised ( refer to glossary for definitions) machine-learning approaches are then used to classify or predict how likely the pair are to be a match.

- Clustering, the final stage utilises a clustering algorithm to group together pairs of records which are determined to refer to the same entity.

In the case of Samagra Vedika, governments had access to over 380 million (38 Crore) existing individual records that could be used to develop the system. Information such as Name and Address appearing in all databases, and other identifiers such as Fathers Name and Date of Birth appearing across some. Without access to the documentation and code, the precise design of each phase of the Entity Resolution pipeline is unknown. However, from materials presented to the World Bank by the Telangana state government, Samagra Vedika appears to use a combination of the following attributes: Name, Address alongside Date of Birth, Phone Number, and Fathers Name, to link the data and compare records.

While no technology is 100% accurate, errors in welfare automation systems can have a particularly high cost and can exclude people from accessing crucial social protection. Qualitative decisions made by developers have a huge impact on people’s lives and rights. In the context of Samagra Vedika, any fallibilities or errors in the data or matching process may incorrectly deem an application a duplicate, leading to a family failing the eligibility criteria for a social protection scheme after errors in the matching process–denying their right to social security.

System developers must define the matching variables upon which the records are linked, which is a complex decision given the innumerable number of variations in how people’s names, date of birth, phone numbers and addresses may be recorded, particularly given the diversity of languages and regional dialects spoken in Telangana.

As shown in Figure X, using machine-learning techniques introduces further complications, as the process requires a “tolerance threshold”, which is likely to be the cutoff which determines what is considered a match or not. This choice is often made to balance the number of false positives and false negatives: In the context of Samagra Vedika, “positive” means fraudulent or duplicative, and “negative” means legitimate. As such, a false positive occurs when the system incorrectly labels a legitimate application as fraudulent or duplicative, and a false negative occurs when the system labels a fraudulent or duplicative application as legitimate. The minimum possible threshold (0) would classify everything as a match (“positive”), hence having zero false negatives but a maximum number of false positives, whereas the maximum possible threshold (infinite) would consider nothing a match (everything “negative”), hence having zero false positives but a maximum amount of false negatives.

Whilst the government claims that false positives are minimised, systems such as Samagra Vedika come at a cost to the state and likely need to justify their deployment. The financial benefits of reducing welfare leakages is the first point that the Telangana State Government IT department makes in its presentation on Samagra Vedika to the World Bank, whereas minimising false accusations of fraud is only mentioned much later in the document. As the UN Special Rapporteur on Extreme Poverty and Human Rights has noted, states “obsessing about fraud, cost savings, sanctions and market-driven definitions of efficiency” often come at the cost of human rights.

Such costs create an embedded incentive to reduce the number of false negatives ensuring the system finds enough fraudulent or duplicative applications and saves public funds. Statistically-speaking the number of false negatives cannot be reduced without risking an increase to the false positives (and vice versa), so this means setting the tolerance threshold becomes a sensitive choice. In practice, a common decision-theory approach used in machine learning is to design a cost matrix that associates a financial cost to each type of error, and attempts to minimise this across all applications. However, the embedded incentive to reduce the number of false positives could, if unchecked, drive the false positive rate higher–meaning eligible people are unjustly excluded from welfare provision. This further underscores the need for transparency for researchers and rights-holders in investigating the workings of such systems.

Lessons from an attempted audit of Samagra Vedika

Technologies that rely upon complex rules and techniques like Entity Resolution, which are difficult to examine and even more difficult to explain to affected people or public agencies that use the system, lead to large gaps in public understanding. This additional layer of complexity brings with it a duty of care for additional transparency measures to ensure the technology can be sufficiently scrutinised by independent experts, and that impacted people are presented with a clear explanation of how algorithmic decisions have been made such that they are equipped to challenge them if needed.

In the absence of adequate transparency measures taken by governments or private companies, public awareness of the workings and impact of such systems has often had to rely upon ‘algorithmic audits’ conducted by journalists and civil society. Throughout 2023, Amnesty International attempted, unsuccessfully, to design and conduct an “external”5 audit of Samagra Vedika. In the long-term, Amnesty International recommends that developers and deployers these systems ensure that such exercises become standard “internal”6 practices by governments and the private sector, who would publicly pre-register their audits, publish their results, and refrain from deploying tools where they stand to violate human rights.

Algorithmic auditing has become a ubiquitous technical research method for diagnosing problematic behaviour within algorithmic systems. It is based upon traditional social science auditing approaches, typically used to study racial and gender discrimination in real world scenarios (e.g., job applications, rental property applications) and comprises a range of approaches such as checking governance documentation, testing an algorithm’s outputs and impacts, or inspecting its inner workings. The basic premise of any audit is to monitor the outcomes of an algorithm, then map these back to the inputs to build a picture for how the algorithm may be functioning. The extent to which each approach is utilised depends on the context of the deployment, and crucially who is conducting, financing and deciding whether to publish the audit (both in terms of access to relevant materials and incentives driving the aims/objectives of an audit).

Algorithmic Audits aim to provide insight into:

- how a system is internally functioning,

- the underlying drivers in the algorithmic design, deployment, or use of data that may be leading to harms,

- the scale at which the system is operating and the number of individuals that may be experiencing harm as a result of its deployment,

- systematic discrimination or bias in the algorithm’s outputs or decisions

In the case of Samagra Vedika, Amnesty International was attempting to conduct an external audit. In an ideal scenario, researchers would gain access to the “holy trinity” of algorithmic accountability materials: the data, documentation7, and the code for a system used by a government agency. In practice, access to these materials is very challenging to obtain.

For this project, Amnesty International and independent researchers who are otherwise unaffiliated to Amnesty International, sought to circumvent access challenges by studying the general purpose Entity Resolution algorithm, EntityMatch, that forms the basis of Samagra Vedika, rather than the bespoke system itself. The audit was designed to assess the impact of the system by submitting fabricated input data to the EntityMatch API, and analysing the received output (Annex 2 provides detail of the audit design). Whilst acknowledging the limitations of this approach, Amnesty researchers pursued this methodology as gaining access to any proprietary software or system was unlikely.

Whilst the impact and contribution of external AI Audits to the algorithmic accountability field is indisputable, they remain extremely challenging due to the lack of transparency from system owners and developers meaning they are a resource and time intensive exercise. Previous studies conducted by journalists, civil society and non-governmental organisations (NGOs) took over two years to complete and had to overcome a series of roadblocks throughout. Amnesty International spent a year designing and attempting to conduct the audit of Samagra Vedika and despite this, the study did not reach completion.

By sharing reflections on this process, Amnesty International hopes to bolster the collective ability of civil society, researchers, and journalists to conduct future research by contributing learnings in this space.

- New methodologies need to be developed where a system is procured from the private sector, as is the case for Samagra Vedika, many digitalized welfare technologies are procured from private companies and this presents a critical challenge to gaining requisite access to a system to conduct research. Most external algorithmic audits that have been conducted “adversarially” by journalists or civil society, rely upon gaining access through the limited provisions provided by freedom of information (FOI) laws (or their equivalents in India – Right to Information). However, in almost all cases, audits have only been successful when the technology has been developed in-house or is legally owned by the public agency in question. Where technology has been procured by a private company, access to code and documentation is usually denied on the grounds that the system is proprietary and therefore should be considered information including commercial confidence, trade secrets or intellectual property8. Such arguments have also been used to hinder transparency in regulation.

- Application Programming Interfaces (APIs) present an opportunity to researchers to help circumvent FOI limitations- as private companies continue to develop systems for the public sector, these may be available to purchase or on a subscription basis directly from the company. This was the case for Samagra Vedika, where although the system was inaccessible, the general purpose Entity Resolution system, EntityMatch, was available for purchase. Although this is imperfect, as the systems are not identical, it represents the next-best viable alternative. Ultimately, the system could not be accessed by independent researchers due to high procurement costs, showing that this is still a significant barrier for investigators and algorithmic accountability workwhich is why this method is not itself a replacement for transparency.

- FOI requests are crucial to understanding the input data structure if considering this approach, Whilst access to the actual data exploited by the system is almost always denied, information on the data structure is not. The RTIs submitted by journalists and researchers unaffiliated to Amnesty International were instrumental to the design of the audit, as they provided detail on the structure of the data that the state government was processing through Samagra Vedika. This provided the basis for Amnesty International to design fabricated data that could be processed through the software.

- Utilising information in the public domain remains crucial, auditing privately-procured systems requires creative approaches that try to triangulate the systems design and input data. Amnesty International gained insight into the algorithmic inputs, data type, and structure through public presentations on the system alongside information on the company’s website. Although often only high-level, it remains useful for building a view of the technology, and finding examples of where IT departments provide this information to partners and other public bodies is critical. It also provides insight on what features of this technology are put forward during the sales process, and thus on the underlying incentives.

- Purchasing software is expensive and shifts too much of the burden onto civil society – calls for further regulatory transparency remain key Purchasing such a system is costly, and researchers may be required to sign an NDA, both of which present huge barriers to this type of research. Whilst APIs should be explored further as an avenue for AI auditing given the exemptions from FOI these systems enjoy, this does shift the burden almost entirely onto civil society. Researchers should continue to call for regulatory transparency, asking for code-accessible versions of the systems to be provided for free to civil society, journalists and other independent auditors.

How Algorithmic Welfare Fails People living in Poverty and leads to Human Rights harms

The Al-Jazeera reports demonstrate how algorithmic systems in welfare can be error prone, which can result in mass exclusions of people from their entitlements, particularly when used at the scale of populations, as they often are. These exclusions can arise from a number of sources – the underlying data on which the algorithmic system operates on might be incorrect or incomplete, or there might be errors in the design of the algorithmic systems themselves.

As the techniques used in Entity Resolution indicate, establishing the thresholds for matching records is far from a simple task. In making such calculations, it appears that some number of exclusions are being written off to algorithmic error. However, when these decisions are left unchallenged and algorithmic errors are not amenable to scrutiny or easy and accessible appeal, they can have devastating consequences such as cutting a family off from food security, income or housing. The increasing reliance on algorithmic systems to make final decisions welfare turns the application of a legal right or entitlement into a stochastic exercise depending on the specificities of an algorithm.

Apart from exclusion and the errors in the output of the algorithmic system itself, the very reliance on data-based techniques implies that governments are accelerating the collection and scrutiny of information about people, often in contexts such as India, where there are few safeguards against its misuse, or against threats to privacy. This kind of surveillance, justified under the pretence of delivering social security schemes, is concentrated on those living in poverty and in need of social security, requiring those often in vulnerable situations to choose between accessing the support that they are entitled to or being further surveilled by the state and private actors.

The manner in which these systems are being put in place around the world is also alarming for the systematic consequences to public accountability and oversight of public administration. In most cases, these systems are contracted from or procured through private actors, who make important design choices which impact how welfare administration functions, which might include establishing thresholds for inclusion or exclusion, establishing rules for classification and eligibility, etc. They are also often less accountable or amenable to democratic processes, such as freedom of information laws, or standards of due process that allow people to challenge wrongful decisions. Independent of the state’s own human rights obligations, private entities have a responsibility to respect human rights as outlined in the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights.

Algorithmic decisions are considered unimpeachable, even though little is known about how these systems analyse data and throw out decisions that impact people’s lives and livelihoods. According to the reports in Al Jazeera, government administrative offices have become so reliant on these systems to administer their schemes that they refuse to overturn the decision taken by the algorithm even when faced with contrary evidence. This means that affected people – who have been excluded or whose entitlements are arbitrarily cut – have little to no recourse to challenging these decisions, or even understanding them.

Conclusion and recommendations

The case of Samagra Vedika, alongside many others9, highlights the need for governments and private actors to provide greater transparency and external access to digitalized welfare technologies. Findings from the Al-Jazeera reports raise significant human rights concerns for Amnesty International, and without greater transparency, systems cannot be sufficiently scrutinised. Whilst progress has been made in the algorithmic auditing space, Samagra Vedika illustrates how challenging conducting an audit of a privately procured opaque system is in practice.

From a policy perspective, questions remain as to what can be done to prevent these failures of accountability in this new era of algorithmic government. Governments must implement transparency and accountability measures in their use of these systems – including testing and auditing mechanisms for algorithmic systems, transparency and explainability measures, and accountability processes and assistance for people affected by these systems. Courts and legislators must ensure strict limits on the use of personal data to counter such experimental uses of data for surveillance. Systemic problems of over-reliance on technological fixes for complex social problems of poverty and social security, coupled with increasing austerity mechanisms that seek to achieve ‘efficiency’ gains by curtailing social welfare must be addressed.

Amnesty International considers that before the introduction of technology into social protection systems, states must carefully consider and weigh its deployment against the potential human rights impacts. It is crucial that the introduction of any technology is accompanied by adequate and robust human rights impact assessments throughout the lifecycle of the system, from design to deployment, and effective mitigation measures as part of a human rights due diligence procedure that contracting companies must be required to carry out. Communities who will be impacted by the system must be consulted and any changes to systems are communicated in a clear and accessible way. Crucially if a system is found to have the potential to harm human rights and that harm cannot be effectively prevented, it must never be deployed.

Amnesty International recommends that all states

- Ensure transparency about the use of digital technologies used by public authorities. While transparency requirements will differ according to the context and use of the system, they should be implemented with a view to allowing affected people as well as researchers to understand the decisions made in the system and how to challenge incorrect decisions.

- Ensure that when a new system is introduced, information about how it functions, the criteria it considers and any appeals mechanisms in place to challenge decision making, are widely disseminated in accessible formats and languages.

- Ensure that digital technologies are used in line with human rights law and standards, including on privacy, equality, and non-discrimination, as well as data protection standards, and that they are never used in ways that could lead to people being discriminated against or otherwise harmed.

- Implement mandatory and binding human rights due diligence requirements of all companies including human rights impact assessment of any public sector use of automated and algorithmic decision-making systems. This impact assessment must be carried out during the system design, development, use, and evaluation, and – where relevant – retirement phases of automated or algorithmic decision-making systems. The impact on all human rights, including social and economic rights, must be assessed and properly addressed in the human rights due diligence process . The process should involve meaningful engagement with relevant stakeholders, including independent human rights experts, individuals from potentially impacted, marginalized and/or disadvantaged communities, oversight bodies, and technical experts.

- Establish comprehensive and independent public oversight mechanisms over the use of automated or semi-automated decision-making systems, to strengthen accountability mechanisms and increase human rights protection, in addition to mechanisms for grievance redressal for individual decisions.

- Factor in and address the multiple and intersectional forms of discrimination that many groups including (but not limited to) women, people with disabilities, older people, people living in poverty, people working in the informal sector, children and people belonging to racialized and otherwise minoritized communities face when trying to claim their human rights, and the specific barriers they may face when interacting when interacting with automated decision making in social protection systems and/or when trying to appeal against a decision made by these systems

- Ensure that companies providing social security systems adhere to their responsibilities as outlined in the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights, as well as their obligations under relevant regional and national corporate sustainability and due diligence frameworks.

Footnotes

[1] Social protection refers to a broader range of contributory (those financed through contributions made by an individual or on their behalf) and noncontributory (those that are funded through national tax systems) programmes. Social protection programmes can include (i) social insurance, such as pension insurance; (ii) employment and labour programmes, including skills training, unemployment benefits, and job search assistance; and (iii) social assistance and cash benefits for those living in poverty.

[2] The Economic Survey of India is a document prepared by the Ministry of Finance summarising important developments in the Indian economy in the preceding year, which often informs the annual budget. <https://www.indiabudget.gov.in/budget2020-21/economicsurvey/doc/echapter.pdf>

[3] Section 8(d) of the Right to Information Act, 2005, provides that (d) “information including commercial confidence, trade secrets or intellectual property, the disclosure of which would harm the competitive position of a third party, unless the competent authority is satisfied that larger public interest warrants the disclosure of such information.” In this case, the authority merely stated that the private company ‘had rights’ over source code and data that was requested, without analysing whether there was a larger public interest warranting disclosure.

[5] Auditors utilise investigative methods to gain access to documentation, data and source code. They’re likely to be only provided a partial view of system, mostly commonly basing their work on model outputs.

[6] Auditors work collaboratively with the system architects and are granted direct access to the documentation, data and source code to assess a system’s impact.

[7] Documentation on system architecture and design, data infrastructure, any relevant governance documentation such as Human rights or equalities impact assessments, conformity or compliance assessments, however this may not always be up-to-date

[8] Section 8.1(d) Right to Information Act (2005)

[9] https://www.lighthousereports.com/investigation/suspicion-machines/ and https://www.lemonde.fr/en/les-decodeurs/visuel/2023/12/05/how-an-algorithm-decides-which-french-households-to-audit-for-benefit-fraud_6313254_8.html

Annex 2: Further details on audit design

Evidence from testimonies and fieldwork with impacted individuals and communities collected by Al-Jazeera researchers and journalists provided the basis of the working hypothesis for this research: that EntityMatch is excluding individuals or families from their social security entitlement, in the name of finding ghost beneficiaries and reducing welfare fraud. Amnesty International researchers also hypothesised the system could exacerbate discriminatory practices and inequalities, if the system is disproportionately excluding specific groups of individuals or families.

The audit was designed to assess the impact of the system by submitting specifically designed input data to the EntityMatch API, and analysing the received output. This would have mimicked the process by which Telangana state government uses Samagra Vedika to process public administrative data, then uses the received output to make decisions on welfare entitlement. The central idea was to submit multiple versions of designed input data fabricated specially to test the system, varying each submission across a number of dimensions such as the number of true matched pairs, and testing the extent to which the system successfully detects duplicated welfare claims, and answer the following research questions:

- Consistency: Is the algorithm arbitrarily excluding individuals or families that are eligible for welfare provision, and on what scale?

- Accuracy: How accurate is the system at identifying true duplicated welfare claims?

- Discrimination Is there evidence of bias or discrimination in the form of systematic exclusion of certain groups?

Amnesty International extends its deepest gratitude to independent researchers who have worked to report on the impacts of the Samagra Vedika system. Their foundational work has made this technical explainer possible.