Gao Zhisheng is a prominent human rights lawyer in China. Over the years, he has been persecuted, kidnapped and sentenced to prison. In August 2017, he went missing again and has not been seen since.

In 2004, I noticed an open letter to the National People’s Congress calling attention to the issue of Falun Gong, a religious group in China. By then, practitioners of Falun Gong had been subjected to large-scale persecutions for five years, but nobody dared to speak up for them. It was very courageous for a lawyer to openly speak about the issue, so I took note of his name: Gao Zhisheng.

The human rights movement in China was just beginning to take off. Active human rights lawyers totaled no more than 20 people. I was eager to meet Gao and was lucky to be able to do so within a few weeks of the open letter. He was tall, spirited and features that radiated with health. I remembered him to be friendly and humorous, and his laughter echoed throughout the room. Nothing angered him more than injustice. We chatted late into the night and, very soon after, began working on human rights cases together.

The first case was that of Cai Zhuohua, a pastor at a house church in Beijing who, together with members of his family, was arrested for operating an illegal business after printing multiple copies of the Bible. It was the first time I witnessed Gao’s grace and eloquence in court. The court disrespected the lawful right of Cai’s mother to observe the hearing, and Gao denounced the judge with fervent conviction. After that, Gao and I would often attend services at house churches in Beijing and he even got baptized later.

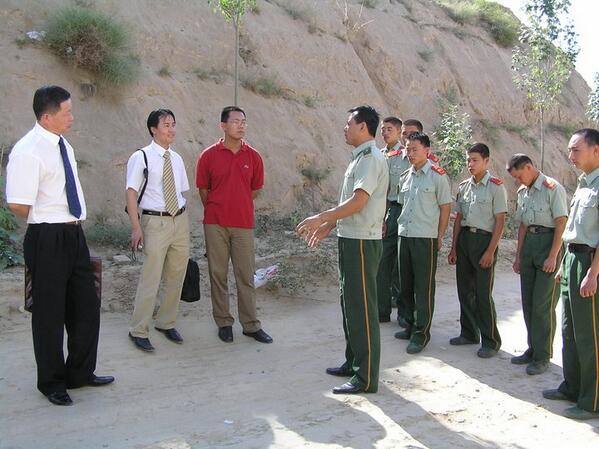

Another case we took on was the case of Shaanxi Oil. At the time, one of the lawyers on the case, Zhu Jiuhu, was arrested and imprisoned at the Shaanxi Yulin Detention Centre. We went to represent him and took pictures at the entrance before we left. Not long after, more than a dozen armed policemen rushed towards us and interrogated us for taking those pictures. They thought they could frighten us, but we were experienced in such interrogation and firmly rebutted them. After that, Gao lamented, “If this is how they treat lawyers in suits, can you imagine what they’d do to the people living around here?”

On the way back, we stopped by Gao’s home in Jiaxian and squatted in the courtyard eating noodles. I will never forget his cave home, his taciturn brother and the dry and barren land that surrounded us.

A coal miner turned lawyer

Gao Zhisheng came from humble beginnings. His father passed away when he was 11. At 16, he was admitted to a prestigious high school but had to drop out because he could not afford the tuition. Before he became a lawyer at 31, he worked a variety of jobs – he picked Chinese herbs in the mountains, worked as a coal miner, soldier and vegetable vendor, and labored in a cement factory. He experienced all kinds of hardships and had a deep understanding of inequality and injustices in China.

After becoming a lawyer, Gao set a few rules for himself. One was that a third of his cases had to be pro-bono lawsuits for low-income groups. He said: “I came from a poor family. I know how poor people feel so I know what I have to do … but helping others should not be an act of charity.”

Gao repeatedly reminded me that people who carry out the orders of authoritarian rule are also victims of it themselves.

Teng Biao

Kindness to plainclothes police

In 2005, he wrote three open letters to Chinese leaders, exposing how authorities had systematically tortured Falun Gong practitioners. While others chose to ignore this gross violation of human rights, Gao ventured all over China to interview practitioners and to defend their rights.

First the authorities shut down his law firm. Then, in the winter of 2005, they started restricting his personal freedoms – around 20 plainclothes police followed him around, and about 10 cars surveilled the area around his home.

“Every morning when I look through my window, I see them jumping up and down to warm themselves up,” Gao recalled. “My wife and I feel very bad for them. So, this morning, we discussed how we can provide these young people with hot water.” He ended up sending hot water to the plainclothes police – not to humiliate them but out of real concern for them. Gao repeatedly reminded me that people who carry out the orders of authoritarian rule are also victims of it themselves.

At the time, human rights lawyers were mostly based in Beijing. We often asked Gao Zhisheng to keep a lower profile, but he never listened. He might have already known that it was too late, or perhaps, he preferred to put up a good fight.

He won widespread respect for his thorough understanding of the legal system and his compassion towards people. Besides the numerous human rights accolades, he was also nominated for the Nobel Peace Prize multiple times. Gao Zhisheng is not “one of” the bravest lawyers in China, he is indisputably “the” bravest one.

Gao Zhisheng is not “one of” the bravest lawyers in China, he is indisputably “the” bravest one.

Teng Biao

Kidnapped

In August 2006, Gao Zhisheng was kidnapped. He later wrote:

“I was walking down the street one day and when I turned a corner, about six or seven strangers started walking towards me. I suddenly felt a strong blow to the back of my neck and fell face down on the ground. Someone yanked my hair and a black hood was immediately pulled over my head.

“… Four men with electric shock prods began beating my head and all over my body. Nothing but the noise of the beating and my anxious breathing could be heard. I was writhing on the ground in pain, trying to crawl away. [One of them] then shocked me in my genitals. My begging them to stop only led to laughing and more unbelievable torture in return.

“I smelled the strong odor of stinky urine. My face, nose and hair were filled with the smell. Obviously, but I don’t know when, someone urinated in my face and on my head.”

His words are painful for me to read today.

Finding Gao Zhisheng

In the 13 years after that kidnapping, Gao Zhisheng has never experienced a day of freedom – he has been either missing, locked up or under house arrest. When Gao was finally seen in public again, he looked old and frail. Most of his teeth were missing. I looked at the photo and could not stop crying.

But time and time again, even after each kidnapping, each imprisonment and torture, Gao Zhisheng refused to surrender.

When he was held in a cave in 2016, he found out that the American Bar Association (ABA) refused to publish my book. He wrote an article to criticize them and to condemn any organization that pandered or succumbed to China’s authoritarian power. Even at his most vulnerable, he refused to be silenced.

In August 2017, Gao Zhisheng went missing again and has not been heard from since. His family and loved ones have never stopped worrying about him.

We continue to look for Gao. We hope that we will soon find his gentle smile, his extraordinary strength, his unrelenting spirit in his fight for human dignity and his refusal to accept defeat.