Doesn’t a woman have the right to decide about her own body? Can’t women defend themselves alone?

Jeshu, 17, Amnesty International activist in Chile

So, you need to have a man by your side? The (school) teacher answered me with a resounding yes

“It takes a village to raise a child”, says the African proverb. But what happens when the village does not want to teach the child? As we grow up, we learn things from our parents, from school and generally from various others; but what if the fundamental things we need to learn are not properly addressed?

For example, sexual and reproductive rights and the freedom to make decisions about one’s own body should not be a matter of discussion because they should be a right guaranteed and promoted by all societies.

However, in Latin America the subject is still taboo, and many young people do not receive information about their rights, or do not find answers to questions that would help them to live their sexuality and relationships to the full. A traditional cultural environment, the lack of open and unbiased information and the lack of comprehensive sexuality education integrated into formal education are, among others, some of the causes of this situation.

This is why in 2016 Amnesty International launched the It’s My Body! programme, involving young people in Argentina, Chile and Peru and made it possible for them to increase awareness and obtain information about sexuality, reproductive and sexual rights, and health services.

Why do I take part? Because I want to see a change in my region. Because I don’t want to be the problem but part of the solution to the problem. Because they talk about me without asking me. They take decisions to improve my well-being, but they don’t do anything. It is important to me that this should not be a taboo but a subject that is given the importance it deserves

Tomy, 16, project activist in Peru

The programme has helped to create opportunities for young people to learn more about their rights, to undertake their first experiences in activism, to feel free to shape their learning and interact with like-minded people. It’s My Body! has put young people at the centre of all its activities, so they are involved in decision-making processes and are represented in all aspects of the programme, as well as gaining the tools to initiate and take part in discussions on issues that matter to them.

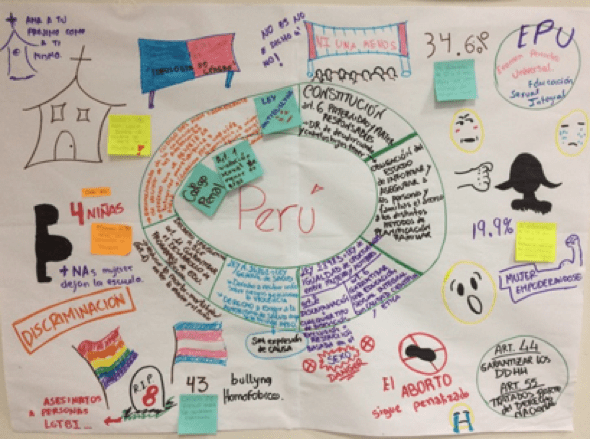

Although cultural context, history and traditions differ in the three countries, they share the same lack of guarantees for sexual and reproductive rights socially, culturally and politically. The programme succeeded in bringing together young activists in one common action, with different results depending on the country and context.

The approaches used throughout the programme have created a network of young leaders, peer educators and workshop leaders to reach out to other young people to inspire them and increase their awareness. The programme also helped to create a new generation of activists who are raising their voices to demand access to their sexual and reproductive rights.

One of the most important aspects for the young people who took part in the programme was the horizontal and non-hierarchical nature of the human rights education tools they worked with. This enabled them to take ownership of the knowledge and the techniques to reach out to more young people and to address issues that are usually difficult to deal with because they are intimate and personal, and because of the nature of their societies.

Personally, I don’t see It’s My Body! as merely an advocacy project for sexual and reproductive rights in Latin America. Rather, it is a new form of activism that makes the young people in the country important through empowering them over an issue that is not exclusively for adults, and in this way generates a circle of learning that is much better.

PI, Amnesty International activist in Argentina

Peer education was also a key focus throughout the programme, and gave rise to circles of learning centred on young people; where creativity, sharing and learning from emotion lay at the heart of education. Peer learning also developed into resistance to adultcentrism that encouraged a new form of activism. Thanks to this approach, young people have felt empowered and able to carry advocacy processes through and thus influence decision making on issues that matter to them.

Illustration: Katherine San Martin.

In addition to increased knowledge about sexual and reproductive rights, strengthened advocacy skills, and generally strengthening young people’s personalities, It’s My Body! achieved real, practical results. For example, in Argentina, one young person successfully reformed a school curriculum to include comprehensive sexuality education. In Peru, young people who took part in the project trained parents and teachers across the country. In Chile, a young man obtained a favourable judgement when defending his case of discrimination at school and appealed to the Office for the Protection of Rights (OPD) and the courts for violation of his sexual and reproductive rights using his human rights knowledge and skills acquired in the project.

My life did not change when I called myself a feminist, or an activist, let alone when I took on the position of coordinator or workshop leader as part of this – wonderful – project, but my life changed when I realized that I was able to change someone else’s life.

(BA) Sofia, 17, project activist in Chile

Political advocacy by young people is one of the main legacies of the programme. The achievement of legalizing abortion in Argentina and the challenge of implementing the law, monitoring of the constituent process in Chile and the struggle to include comprehensive sexuality education in the education curriculum in Peru are strategic lines of Amnesty International’s work that will be able to count on the active participation and involvement of young people beyond the It’s My Body programme!