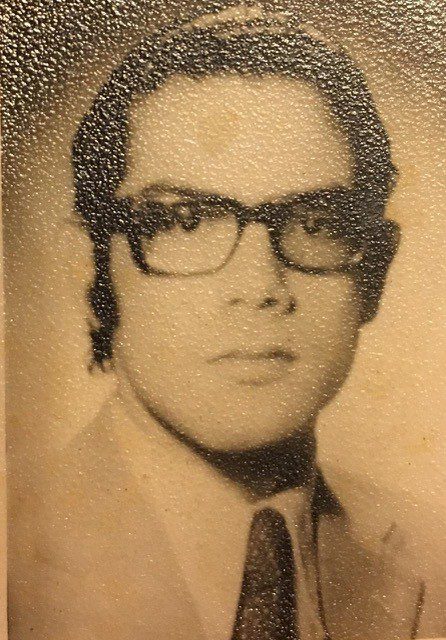

Nestor Fantini, 65, was arrested for speaking out as a student. He spent four years in prison, where he was tortured and beaten. When a young student started campaigning for his release, with the support of Amnesty International, his life changed more than he could have ever imagined…

I grew up in a traditional middle-class family in Argentina, where I was taught the importance of democracy. Yet, as I travelled to Northern Argentina, I saw how marginalised some parts of the country were. It was a shock. What we were taught in class, didn’t match up to reality.

I became a student activist during college and started speaking up against the status quo. When democracy was restored in 1973, I felt lucky to have been involved in that process – but my name was tainted. The government was worried about student politics and the trade union movement and I was arrested in September 1975 for speaking out. An officer involved in my arrest told me they’d been looking for me for a year.

I was taken to D2 [a unit of the local police station], where I was interrogated. It was like a centre of torture. I was thrown into a tiny cell, along with 12 others, where I was blindfolded, handcuffed and beaten. They accused me of being a terrorist. I was stripped naked, shoved on a metal bedframe with no mattress, and [electrical] cables were attached to my genitals and armpits. The pain was unbearable. They even put a gun inside my mouth and told me they were going to blow me up.

My interrogation lasted six days, before they took me to UP1 prison in Córdoba. They took everything away, leaving me with just clothes, a mattress and blanket. I spent all my time in a cell where, again, I was subjected to torture. I was one of the lucky ones though – 31 of my fellow inmates were executed. In fact, in 2010, 15 officials were found guilty of crimes against humanity in connection to the executions and torture committed in Cordoba prison.

I was just 22 at the time – and I remember feeling as though I was making an important contribution to society. I was an idealist, who didn’t realise the full gravity of the situation.

When I was transferred to Sierra Chica prison in Buenos Aires, I knew there was a chance of survival. While I was there, my mother and sister came to see me. My mother told me she’d been reaching out to organisations to tell them about my case. When she told me Amnesty International were involved, I felt so hopeful.

A passionate PHD student called Mary Evelyn Porter, or Mev as she was fondly known, was spearheading the campaign. As I was only allowed to receive letters from relatives, Mev would send letters of support to my sister who would deliver them to prison under her name. It was incredible to think people in places from Bangkok to London were supporting me. There and then, I knew it would be far more difficult for those in power to kill me.

My outlook on life changed dramatically. The letters signalled hope – millions of people knew about my case and Mev was leading the charge. Her kindness and support provided me with hope that there was a future. It made the world of difference.

Mev’s work brought her to Argentina and on July 14, 1979, she came to see me in prison together with my mother – they’d become close friends. In an incredible turn of events, I was released that same day.

No one was more surprised than me when they called out my name. As I left, I was told “don’t look back”. I didn’t. Ahead of me, I saw my mother and, who I was soon to learn was, Mev. We were both carrying the same book – Ulysses by James Joyce – mine in Spanish, hers in English. We quickly became great friends. Things started developing in a new direction, but to be honest, I started falling in love with Mev way before I met her. The letters themselves created a very powerful emotional connection. We got married and eventually welcomed our son, Jonathan, into the world in 1984.

Even though Mev and I have divorced, we remain close and visit each other often – especially around Thanksgiving. We’re so proud of our son. He has worked in international security and was featured in Forbes’ 30 under 30, where he was named one of “the brightest young entrepreneurs, breakout talents and change agents”. My story is one Jonathan is proud to tell and he often shares it at high-level events. He’s passionate about human rights and just recently, Jonathan was in Argentina, participating in the Mothers of Plaza de May march. It’s great to see him continue down this path.

Amnesty International is so special to me and its support will remain in my heart for the rest of my life. It appeared at a critical moment and, since then, many of my most special moments have been connected to Amnesty International. I remember meeting Mev’s Amnesty International Group, which was incredible. If I had the opportunity, I would love to meet every individual who wrote to me and give them a big hug – I am a hugger!

Letters aren’t just a simple gesture of solidarity, they become a source of hope and they have the potential to change people’s lives. I am living proof. Your letters gave me the self-confidence, hope and energy to live a full and successful life. After I was released, I went to university and became a teacher. I taught for many years, I raised a family and now I have a child that I love more than anything in the world.