“I felt very excited when I heard that I will be working at the stadium. I had a lot of confidence in me that things were going to be better there… because I know definitely the living conditions would be quite okay, the payment of salary also would definitely come… but to my surprise things didn’t work as I was expecting.”

(Noah, a father of two and QMC employee)

Arriving in Qatar almost a decade after FIFA awarded the country the 2022 World Cup and following the Gulf state’s widely touted promises to reform its labour laws, it is little wonder that Noah and his friends had high expectations about what would await them. Labour abuse should be old news in Qatar by now, they thought.

So, when they were asked to help build the façade of one of the country’s most prestigious stadiums, they felt they’d hit the jackpot. After all, they were working on a World Cup project, where employees are often referred to as “first-class workers”, because the higher welfare standards demanded of employers on these sites compared to others in Qatar, should mean they are better protected from labour abuses.

The last thing Noah and his colleagues expected was that they too would find themselves victims of exploitation: unpaid wages, deceptive recruitment practices, expired residence permits and no possibility of changing jobs.

In this article Amnesty International documents the case of around 100 migrant workers employed by Qatar Meta Coats (QMC) to work on elements of the €770m Al Bayt Stadium, a construction project for the 2022 FIFA World Cup in Qatar.

These workers worked for up to seven months without pay, and are still owed outstanding salaries despite some workers receiving partial payments on 7 June. The company has also failed to renew their residence permits.

The problems faced by QMC workers were well-known to Qatar’s Ministry of Labour and the country’s World Cup organising body for nearly a year, but compensation only began after Amnesty International shared the findings of its investigation with these bodies.

The plight of these workers is yet another reminder of the harsh reality migrant workers still face when things go wrong during their employment in Qatar, despite the introduction of reforms in recent years. It also shows that no matter where you work, no matter how prestigious the project, and no matter the welfare standards in place, the risk of labour abuse is still very real, hard to escape and even more difficult to get justice and remedy for.

Today, these workers are still waiting to receive their full salaries and Amnesty International is joining forces with them to call on Qatar and FIFA to ensure they get every penny they are owed, and to fix a system that has too often failed migrant workers.

No one should work for free, let alone when delivering one of the world’s most popular sporting events in one of the world’s richest countries.

Methodology

Amnesty International spoke to seven current and former employees of QMC and received credible evidence about five others. The organization also reviewed employees’ contracts, pay slips, official correspondence from the Committees for the Settlement of Labour Disputes, and workers’ security passes for Al Bayt Stadium.

The organization reviewed publicly available corporate information to establish facts regarding the contractual chain on the Al Bayt Stadium Project, and engaged in detailed correspondence with all companies and entities concerned, raising concerns and seeking their response to the allegations.

Allentities provided Amnesty International with written replies, extracts of which are included below. The complete company responses can be found here and the response from Qatar is here.

Amnesty International has changed the names of the individuals quoted in this report to protect their identity. The organization urges all parties concerned to ensure no employee faces reprisals. Any reprisal would be contrary to international human rights standards.

Labour abuses

Al Bayt Stadium will be one of the 2022 World Cup’s crown jewels, expected to welcome around 60,000 fans as it hosts matches through to the semi-finals. Beyond the tournament, the stadium will also be home to a branch of Aspetar, a world-leading sports medicine facility that already treats international athletes and sports people and has partnerships with leading international football clubs such as Tottenham Hotspur and Paris Saint-Germain.

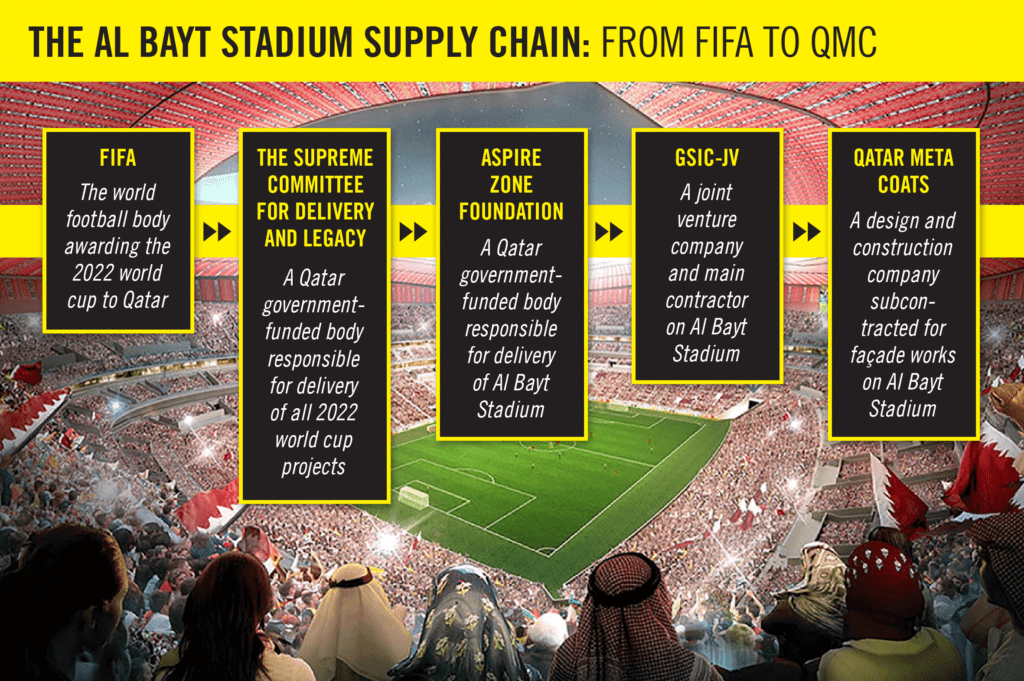

Work on all World Cup sites in Qatar is carried out under the auspices of the Supreme Committee for Delivery and Legacy (the Supreme Committee), the body set up by the Government of Qatar to deliver the tournament. Specifically, the delivery of Al Bayt Stadium is the responsibility of another government-funded organization, Aspire Zone Foundation (Aspire), which appointed the GSIC-Joint Venture (GSIC-JV) company as the main contractor for this project in 2015. In 2017, GSIC-JV in turn subcontracted Qatar Meta Coats, a design and construction company, to complete the design and installation of the façade works for Al Bayt Stadium and to supply manpower to the project.

The employees with whom Amnesty International spoke were migrant workers from South East Asia and Africa, who had arrived in Qatar and begun working for QMC between 2017 and 2019. All of them faced a range of labour abuses during this period; from unpaid salaries to expired residence permits, the payment of recruitment fees and restrictions on changing jobs, leaving them stuck with an employer who isn’t paying them.

Months of unpaid salaries

QMC employees who spoke with Amnesty International said that they started facing salary delays in early 2019, and between September 2019 and the end of March 2020 many employees received no salary at all for their work. Other workers were also not paid their August 2019 salaries.

Those interviewed told researchers that they believe the delay in wages affected all QMC employees who were engaged on the Al Bayt Stadium project, estimated to be around 100 people. At the end of May 2020, the amounts owed to workers and staff ranged from around 8,000 QAR ($2,200 USD) to over 60,000 QAR ($16,500 USD).

Employees told Amnesty International that prior to 2019, QMC would pay their salaries on time each month. However, they said that in early 2019, payments gradually became delayed, first by around one month and then increasing to three months.

Ben, who started work with QMC in 2019, expressed his shock at the situation in which he quickly found himself:

“I came here to work for money, and it is the company that brought me here. You bring me here and you refuse to pay my salary? And you don’t tell me anything even.”

Tired and frustrated of working hard without any income, workers started raising their concerns with the company’s managers, requesting their money. They complained to both the Managing Director and General Manager and received repeated promises that they would be paid imminently, but these promises proved to be empty.

Ellison, another QMC worker described how the company repeatedly pledged to pay them.

“Every day we are asking but they are telling us ‘we are having a shortage of money’. They tell us they are trying their best. ‘At the end of this week’, they tell us.”

Father of three, Daniel, who has worked for QMC for more than two years, said:

“We had more than 50 promises. They would call and say ‘next week’. Even now they called us last week. But it is empty promises, about 50 to 100 promises but they are all empty! I don’t think they will pay us, I don’t know why.”

Eventually, in February, QMC stopped its employees from working on the stadium and moved them to a new accommodation in the New Industrial Area of Doha where they are now living in cramped rooms, shared by up to six workers.

They were then asked to report to the QMC factory, which makes a range of aluminium and steel materials that workers understand were intended for use in the Al Bayt Stadium. The majority of workers continued to work there without pay until 22 March 2020, when the factory was temporarily closed due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Unexpectedly at the end of March, having not been received any wages since September 2019, workers were given one- or two- months’ wages each. After that, payments stopped again until early June. In a letter dated 12 April 2020 in response to Amnesty International’s allegations, QMC recognised the persistent non-payment of salaries, stating that the company has “faced difficulties with salary payment” due to financial problems, and claimed it was “in the process of acquiring the funds to pay off the salaries.”

Expired residence permits and obstacles to changing jobs

Most of the workers interviewed also faced other problems due to QMC’s failure to renew expired residence permits. Some also claim they were prevented from finding a new job when the company refused to grant them the No Objection Certificate (NOC) required under Qatar’s sponsorship law to allow them to change employer.

According to the sponsorship law in place in Qatar, companies that sponsor migrant workers are obliged to provide them with valid identity documents. Without valid residence permits migrant workers become illegal in the country and at risk of arrest and deportation. Additionally, employees will not be able to renew their health cards, leaving them at risk of not being able to access vital health care.

Similarly, under Qatar’s kafala system, employers have the power to prevent a worker from changing jobs by refusing to sign a No-Objection Certificate if the worker is still under contract. If an employer reports a worker as having “absconded” from their job without such permission, the worker can face arrest and deportation. In cases of abuse such as unpaid salaries, workers can, if they are able to secure another offer of employment and meet certain criteria, request a job transfer without their employer’s permission, but even then the worker will face other administrative barriers.

Father of two, Noah, told Amnesty International: “I requested a No-Objection Certificate, but HR told me there is no way they will give me it because I didn’t finish my contract.”

Other workers told Amnesty that they had heard from colleagues that the company did not grant NOCs during contract periods, and so felt there was no point in asking for permission to move jobs, despite not being paid for months.

Even if a request had been approved, however, a job transfer may still prove difficult. For example, if an employer like QMC has not renewed the worker’s permit, penalties will accrue, and it is the worker – not the employer – who must pay the fines before requesting a transfer. Workers in financial difficulty because of unpaid wages – such as those at QMC – are not usually in a position to pay these fines and may be more likely to keep working in the hope that the company eventually fulfils its promise to pay.

In its written response to Amnesty International, QMC acknowledged that the company has not been able to renew workers’ legal documentation due to its financial difficulties. It also said that Qatar’s Ministry of Administrative Development, Labour and Social Affairs (MADLSA) had met with the company and granted it until the end of April to “sort our issues”, including paying salaries and renewing workers’ legal documentation. QMC denied claims, however, that it had refused to allow workers to change jobs, stating “We have been more than willing to grant NOCs to employees who have requested for it”.

In its response, GSIC-JV reiterated this claim, and further wrote that QMC had assured the company that it is in the process of renewing all expired health cards. However, to date, neither residence permits nor health cards have been renewed.

Recruitment fees

Like so many migrant workers who come to the Gulf, QMC workers also paid large and often unlawful fees to recruitment agents in their home countries to secure their jobs. Those interviewed by Amnesty said they paid between $900 USD and $2,000 USD, often having to take out high-interest loans to do so.

The charging of excessive recruitment fees is one the first exploitative labour practices migrant workers often fall victim to, even before they land in Qatar with its notoriously abusive kafala sponsorship system. The debt incurred places workers in a highly precarious situation, vulnerable to exploitation by abusive employers, and facing huge problems when salaries are not paid.

Kiran, a QMC worker who arrived in Qatar in 2019, told Amnesty how he had to take out a bank loan and borrow money from a friend to pay the thousands of dollars charged by a recruitment agent in his home country. He had high hopes of paying the loan back quickly and building a better future for his family, but having not been paid for months this has been impossible. Now, with no salary, he finds been himself accruing interest on his loan each month, forcing him deeper into debt, and putting his family at risk of serious penalties. While many of his co-workers wish to return home after their traumatic ordeal in Qatar, Kiran feels he has no option but to remain in the country until he earns enough to climb his way out of debt.

The charging of workers for recruitment fees and associated costs is prohibited by Qatar’s Labour Law any such costs should be paid by the employer, and is a violation of international labour standards which state that “No recruitment fees or related costs should be charged to, or otherwise borne by, workers or jobseekers.” The Supreme Committee’s Workers’ Welfare Standards governing companies delivering World Cup projects, such as the Al Bayt Stadium, also require that companies bear the costs of recruitment.

In its reply to Amnesty International, QMC stated that the company does not charge its workers any recruitment fees, while GSIC-JV said that it had contractual agreements to prevent this, and would be “raising this concern with Qatar Meta Coats in an effort to find a solution”.

The Supreme Committee told Amnesty that it had also found that QMC workers had paid recruitment fees during its own audits of the company, and stated that QMC had declined to join its voluntary ‘Universal Reimbursement Scheme’ in which companies engaged in World Cup projects are encouraged to repay fees even without receipts.

While workers paid agents back in their home countries rather than Qatar Meta Coats themselves, the responses from both QMC and GSIC-JV to Amnesty’s allegations may suggest a failure to recognise, mitigate and address this well-known phenomenon.

Workers’ hardship

Employees explained to Amnesty International that the salary delays, recruitment fees and administrative problems had caused them significant hardship, particularly for those who are supporting not only themselves, but also their dependants at home.

Daniel told researchers that his son was no longer able to go to school as he could not afford to pay his school fees:

“We don’t know what to do. We don’t have residence permits, we are here illegally. Our employer can run away at any time, he is not a Qatari national. We are heading to seven months without salary. Me, personally, I am okay, but what about my kids? Now my eldest child is at home, he cannot go to school.”

Kiran explained that he was the only person supporting a sick relative in his home country.

“Before December last year my father got really sick. I am the only one caring for him, he was too much sick and was admitted to hospital. I had to borrow money from a friend when he went into hospital”

Others said they were struggling to pay back loans taken out to cover recruitment fees paid to local agents before they came to Qatar.

Ben, summed up the powerlessness he still feels in Qatar, despite all the country’s promised reforms:

“We want [Amnesty] to help us because the rules are there, but the rules are not working. I can see they are favouring the companies because when you take your case to court, instead of helping you, they will not do it. You will suffer. We don’t have salary, we don’t have money to go to court, so we have to ask friends, we have to beg. Only God knows what is going on. We are suffering. Now our family is calling us for money. They say we should come back because they don’t want us to suffer.

He continued,

“some of the companies, they are not sticking to the rules. What I want to say to Qatar is: the rules are not working. We are all human beings. If God helps you to be in the position you are in, it doesn’t mean you should let people suffer. They are not doing the right thing. In my country I am not suffering, but I came to make money. I am a human being.”

Mediation and Retaliation

Fed up of the company’s repeated unfulfilled promises to pay them, a number of workers attempted legal action to recoup their lost earnings. By the end of January 2020, around 25 workers had submitted complaints to Qatar’s Committees for the Settlement of Labour Disputes (Committees) – a reformed system of labour tribunals launched in 2018 that promised rapid justice, but which has been beset with delays.

After the complaints were submitted, QMC and its employees were called to mediation sessions. Workers told Amnesty International that during some sessions the company’s representatives agreed to settle the claims, but subsequently failed to pay as promised. In other cases, the company said it would settle the employees’ dues only if they agreed to leave their job and return to their home countries, despite some having at least a year left of their two-year contracts. When some employees refused this offer, feeling unable to return home early after the expense and sacrifices made to get to Qatar in the first place, some were stopped from working altogether and were left in the camp day after day, apparently in retaliation for their refusal.

Kiran told Amnesty, “The company has so much advantage over workers that you regret going to the court. The situation here in Qatar is too much. Whatever the company decided to do, it favours them. Workers are suffering because the companies rule.”

At the time of writing, none of those interviewed who had submitted complaints in early 2020 had received dates for their first hearings before the Committees, something that should have happened within 20 days of their initial submission.

In response to allegations that QMC penalised workers who complained to the labour committees, the company told Amnesty International that its employees “have never been discouraged to report their grievances to the HR Department” and that “All grievances have been dealt with in a mutually understandable way.”

Remedy now in sight?

Despite these long-held frustrations, since early June things have started to change after Amnesty shared the findings of its investigation with the companies, the World Cup organisers and the Qatari authorities. Finally, on 7 June, workers begun to be paid at least some of what they are owed, and on 8 June the Supreme Committee told Amnesty that workers had been paid four months of unpaid wages.

Amnesty has spoken to a number of staff and workers, who confirmed that some of them have indeed received two to four months’ basic salary – out of seven months owed – but without any of the overtime or additional allowances they are contractually entitled to. They also reported that some workers have not yet received any payments at all.

While it is clearly positive that some payments are beginning to be made, the outstanding amounts owed – both in terms of allowances and unpaid months – remain substantial. For example, in one contract reviewed by Amnesty International, the basic salary of 1,000 QAR ($274 USD) per month was complemented by additional allowances amounting to 500 QAR ($138 USD), excluding overtime. This means that when this worker is paid his basic salary only, he is in practice being denied at least one third of his total wage.

In regards to the months of salary that have not yet been paid, on 8 June the Supreme Committee wrote to Amnesty to say that they “will continue to follow-up with MoADLSA until the matter is satisfactorily resolved and all owed payments are made.”

The responsibility of businesses to respect human rights

Under international standards on business and human rights, all companies must respect all human rights, including labour rights, of their workers. This is articulated in the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights (UNGPs).

This responsibility exists independently and regardless of whether the state has met its duty to protect individuals from corporate harm. Companies are thus responsible for how they treat their employees and should protect their human rights including their right to work, which entails the right to fair remuneration, just and favourable conditions of work.

In line with international standards, companies should also exercise due diligence to identify, prevent, mitigate and – where necessary – redress human rights abuses connected to their operations. In addition, the UNGPs make clear that each worker whose human rights have been abused has the right to an adequate remedy under international law: Companies have a responsibility to provide an adequate remedy when their operations have led to human rights abuses.

Qatar Meta Coats is the ultimate perpetrator of the abuses against its employees and must provide full and effective remedy for its workers immediately.

By continually failing to pay employees on time and provide them with valid documentation, Qatar Meta Coats has failed to meet its responsibilities to respect human rights, in breach of international standards as well as Qatari laws and regulations. This includes Qatar’s Labour Law, which requires employers to pay workers at least once every month, prohibits the payment of recruitment fees, and the sponsorship law which obliges companies as the main sponsor of migrant workers to provide them with valid identity documents.

In the context of Qatar, where the impact of exploitation and abuse on migrant workers has been well documented by Amnesty International and others over many years, it is especially important that companies undertake due diligence and remediation processes are implemented and adhered to. In practice, this means that QMC should take measures to prevent and remedy such impact, for example by immediately paying all employees their outstanding salaries, renewing their residence permits, ensuring that all recruitment fees charged to employees are repaid, and providing them with NOCs allowing them to change jobs if they so wish.

Other contractors in the supply chain also have responsibilities to respect human rights. It appears that GSIC-JV and Aspire have taken some proactive steps to try and resolve the payment issues, however it is clear these have been ineffective in stopping abuse and securing adequate and timely remedy.

Responding to the allegations regarding its subcontractor QMC, the main contractor on Al Bayt Stadium, GSIC-JV, told Amnesty International that the joint venture company uses “its best efforts and all leverage at its disposal to ensure that all its subcontractors on the Al Bayt Stadium Project comply with and adhere to the requirements of the Supreme Committee for Delivery and Legacy’s Workers’ Welfare Standards”.

GSIC-JV confirmed that all its contracts require compliance with the Workers’ Welfare Standards, and that QMC are no exception. The company claimed that it followed all processes in place to ensure full and timely payment of salaries by subcontractors. In this instance, when they were alerted in late 2019 that QMC had failed to pay its workers, GSIC-JV issued several warnings to the company between October 2019 and February 2020 “instructing it to make immediate payments to its workers and requesting proof of payment.”

After QMC continued not to pay the workers, GSIC-JV says that alongside Aspire and the Supreme Committee, it then exerted joint pressure on QMC, resulting in the company committing to pay all pending salaries up to December 2019, by 13 February 2020. Unfortunately, these commitments were again not fulfilled.

GSIC-JV explained that in the past it has directly paid workers when its subcontractors failed to do so. The Supreme Committee told Amnesty that it had encouraged GSIC-JV to do similar in this case. However, in this instance GSIC-JV claims this was not possible, because of “assignment by Qatar Meta Coats of its payment rights to a third party”, meaning it is obliged to make payments directly to the bank only, and is not authorised to pay the QMC workers themselves. GSIC-JV say they unsuccessfully requested the bank to deviate from this assignment on two occasions so that it could pay the workers directly.

GSIC-JV committed to continuing to use its leverage to push QMC to find a solution and said it will issue a final notice to QMC and could blacklist the company from any future projects if it fails to sufficiently remedy workers for the abuses suffered. Ultimately, however, GSIC-JV states that it is “unfortunately not in a financial or legal position to make direct payment to Qatar Meta Coats”.

The Supreme Committee

In 2018, almost four years after their introduction, the Supreme Committee for Delivery and Legacy updated its Workers’ Welfare Standards, a set of labour standards and protections which are included in contracts awarded to companies working on World Cup sites. The standards cover issues including ethical recruitment, timely payment of salaries, health and safety, employment, working and living conditions and the provision of grievance mechanisms. All companies working on World Cup projects must comply with the standards – this includes Aspire, GSIC-JV and Qatar Meta Coats.

“The SC [Supreme Committee] affirms that all contractors and sub contractors engaged in the delivery of its projects will comply with the principles set out in this Charter as well as all relevant Qatari laws. These principles will be enshrined in SC’s contracts and will be robustly and effectively monitored and enforced by SC for the benefit of all workers. Compliance with this Charter and all relevant Qatari laws will be a prerequisite to the selection and retention by the SC of its contractors and sub contractors. The SC is committed, and shall require its contractors and sub contractors, to adhere to the following principles in their treatment of all workers…:”

(The Workers’ Charter, preamble to the Workers’ Welfare Standards)

While these standards have improved the working and living conditions for people contributing to the delivery of the 2022 World Cup, six years after implementation they are not universally respected. As a result, workers such as those employed by QMC continue to face labour abuse despite working on Supreme Committee projects.

The Workers’ Welfare Standards commit the Supreme Committee to carry out regular auditing to ensure contractor compliance, and, where a breach is found, there are several measures the Supreme Committee could take, including blacklisting the offending company, terminating its contract or suspending payment. A further remedial option listed in the Standards is “SC [Supreme Committee] rectification at Contractor’s cost”, which would see the Supreme Committee remedying the situation directly itself and subsequently recouping the costs from contractors.

In its letter to Amnesty International dated 29 May 2020 and in response to our allegations, the Supreme Committee said that it first became aware of salary problems at QMC in July 2019, as a result of its ethical recruitment audits, interviews with workers and complaints received through its grievance hotline. It confirmed Amnesty International’s key findings, including the non-payment of wages of workers, and the non-renewal of residence permits and health cards, and said that it has been working “to find a solution for the affected workers”.

The Supreme Committee wrote that, alongside Aspire and GSIC-JV, it exerted pressure on QMC that led, in October 2019, to the company paying the salaries for July and August. It also outlined the steps taken to try and secure later unpaid salaries, including suggesting to GSIC-JV that it pay QMC directly, reporting the company to MADLSA and blacklisting QMC from future contracts. Further, after QMC failed to meet a deadline in February to pay outstanding salaries, the Supreme Committee ‘demobilised’ QMC from Al Bayt Stadium on 23 February 2020. Although the Supreme Committee conceded it had not “yet arrived at an acceptable solution”, it committed to continuing to “pursue the options available to us until the workers have received their outstanding salaries.”

Aspire’s response to Amnesty’s allegations provided a very similar account of the timeline and steps it has taken in collaboration with the Supreme Committee since July 2019.

Following this letter, things started to move. In a communication on 5 June, in response to further questions from Amnesty, the Supreme Committee informed Amnesty that QMC’s owner had been detained and had now pledged to start paying salaries on 7 June, and on 8 June told Amnesty that four months of salaries had now been paid.

Amnesty International recognises that the Supreme Committee’s audit mechanisms allowed it and Aspire to identify issues within QMC at an early stage, and to take some steps in an attempt to address the abuses. Despite this, the exploitation of around 100 migrant workers was allowed to continue for many months, and remedy was slow to come – and is not yet complete. In particular, it is unclear if the Supreme Committee itself sought to make use of the rectification clause in its Workers’ Welfare Standards allowing it to directly remedy the workers at QMC’s subsequent cost.

Despite the fact that some compensation has now begun to be paid, the QMC workers’ plight has exposed the limitations of the Workers’ Welfare Standards when companies are apparently unable or simply unwilling to pay.

FIFA

In 2017, FIFA established a Human Rights Policy laying out its commitment to respect and promote human rights throughout its activities, in line with the UNGPs. It recognises that, like all companies, FIFA must ensure respect for workers throughout its supply chains.

“FIFA strives to uphold and promote the highest international labour standards, in particular the principles enshrined in the eight core International Labour Organization conventions. It implements relevant procedures in relation to its own staff and seeks to ensure respect for labour standards by its business partners and in the various activities directly linked to its operations, including through its supply chains.”

(FIFA’s Human Rights Policy, May 2017 edition)

In January 2020, FIFA, the Supreme Committee and the FIFA World Cup Qatar 2022 LLC, a local organizing committee, also jointly published a new Sustainability Strategy, with the aim of improving the working and living conditions of people contributing to the delivery of the 2022 World Cup, as well as other human rights and environmental issues.

Within the new Sustainability Strategy, FIFA and its partners pledge to “safeguard the rights and welfare of workers engaged on FIFA World Cup 2022™ sites”. They also rightly acknowledge that where they have caused or contributed to an adverse human rights impact, they have a responsibility “to provide for or cooperate in remedying adverse human rights impacts on these workers where such impacts may have occurred.”

Given the QMC workers were directly working on the Al Bayt Stadium, where matches will be played through to the World Cup semi-finals, there can be little doubt that FIFA’s commitments, as the tournament’s ultimate organiser, extends to this case, and that to date they have not been met in this instance.

In a letter dated 9 June in response to Amnesty International’s allegations, FIFA confirmed the key findings of the case, including the non-payment of wages to workers, payment of recruitment fees and non-renewal of health cards. It confirmed its subsequent engagement with Qatar and its World Cup partners and highlighted steps taken by the Supreme Committee to try to rectify the issues. It further welcomed the “decisive steps” taken by Qatar against QMC’s owners in recent weeks, which FIFA says were critical to ensuring workers received some payment on 7 June.

The letter states that “day-to-day due diligence” of construction workers’ rights is led by the Supreme Committee which has put in place “robust and transparent systems to address labour rights risks” of World Cup workers, the effectiveness of which FIFA says it “has every reason to trust”.

In response to follow up questions, FIFA confirmed that it was not aware of the situation faced by QMC workers on its stadium until May 2020 when Amnesty first informed the Supreme Committee. It also said that is not “routinely notified” of all cases requiring remediation, instead trusting its partners and their systems in place to protect workers’ rights on World Cup sites.

As a result of this case, FIFA nevertheless pledges to review its processes and systems with its Qatar World Cup partners, and to use lessons learned from this case to strengthen its own mechanisms.

Amnesty International recognises that FIFA has played a role in the recent partial payment of wages by engaging with key parties after becoming aware of the case in May. However, by delegating its own responsibility of day-to-day human rights due diligence to the Supreme Committee and failing to seek regular updates on the human rights situation of workers on its stadiums, FIFA failed to become aware of and adequately remedy the plight of QMC workers for almost a year.

Above all, this case shows that for the past ten years, FIFA has failed to put in place and implement its own human rights due diligence systems to monitor the human rights situation in its own supply chains and identify, prevent or mitigate human rights abuses, and to provide for or cooperate in remediation where appropriate.

Beyond this, Amnesty International and many others have repeatedly called on FIFA to use its leverage with the Qatari authorities to press for meaningful reform of the country’s labour system which presents fundamental structural problems and allows employers to have excessive control over migrant workers. And while Qatar has made welcome changes to the kafala sponsorship system in recent years, the continued exploitation of workers show there remains a great deal left to do.

FIFA pledges in its Human Rights Policy to “strive to go beyond its responsibility to respect human rights…by taking measures to promote the protection of human rights and positively contribute to their enjoyment, especially where it is able to apply effective leverage to help increase said enjoyment”, and in the foreword to the Sustainability Strategy, FIFA’s Secretary General states that the organization is striving to leave “a legacy of world class standards and practices for workers in Qatar and internationally”.

Since awarding the 2022 World Cup to Qatar nearly ten years ago, FIFA has failed to take its own clear, concrete action to prevent human rights abuses of workers on World Cup-related projects. Instead, it has continued to delegate the heavy lifting of human rights due diligence to the Supreme Committee. By doing so it is using the Supreme Committee’s systems as an excuse for its own inaction, allowing it to simply pay lip service to the remediation of human rights violations and to allow them to continue with impunity.

If FIFA’s pledges are to prove meaningful, it must hold its partners to account, and increase use of its leverage with the Qatar government. This should include publicly calling on the government to fulfil its promises on workers’ rights to ensure they are in line with international law and standards, so that no company – whether employing people to construct a World Cup stadium, serve in restaurants or guard hotels – can abuse and exploit its migrant workers with impunity.

Qatar’s responsibility to protect human rights

As part of its duty to protect people from abuses of their rights by third parties like companies, the Qatari authorities should be taking action to prevent, investigate, punish and redress abuse.

As a state party to international treaties including the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights and the Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, Qatar is not only under a duty to ensure the full respect and protection of people’s rights living and working in Qatar, but also to provide remedies when those rights are being violated, including by third parties such as companies. The right to remedy encompasses the victims’ right to equal and effective access to justice, and adequate, effective and prompt reparation for the harm suffered.

On 10 June, in a late reply to Amnesty International’s allegations, Qatar’s Ministry of Labour stated that as a result of QMC’s salary delays,a report was issued for the first time in October 2019. Immediately after this, the company was reportedly “banned”.

As for the actions taken by the Ministry to ensure affected workers receive their unpaid wages and compensation, the letter simply states, “The company pledged to paythe full wages in the first week of June 2020.” However, at the time of writing, only some partial payments were made to some workers during this week. They continue to be owed substantial amounts and it is unclear what steps Qatar plans to take to ensure these are cleared completely.

While QMC clearly failed to respect the human rights of its workers, and actions taken by companies in the supply chain were unsuccessful in securing timely payments, the Qatari state also failed to fulfil its duty under international law to protect their rights.

Despite being made aware of issues at QMC in September 2019, the steps taken by the authorities were insufficient to stop the abuse and compensate the workers in a timely manner.

Over the past few years Qatar has introduced a number of promising mechanisms to enable identification of abuse, and improve workers’ access to justice and remedy. For example, the non-payment of salaries to QMC employees should have quickly been identified by the government’s Wage Protection System which should have triggered further investigation and remedial actions by the authorities. Furthermore, workers who brought complaints to the Committees for the Settlement of Labour Disputes between October 2019 and early 2020 should have received positive judgements within a six-week timeframe, and be paid their outstanding salaries from the Workers’ Support Fund if QMC failed to do so.

While recent action by MADLSA to pressure QMC’s owner to begin to pay wages has provided some compensation for workers, Qatar’s authorities nevertheless failed for nearly a year to stop the abuse, hold QMC to account or provide remedy for workers forced to work for months in a row for free.

Conclusion and recommendations

The plight of the QMC workers at Al Bayt Stadium shows that migrant workers in Qatar continue to be vulnerable to exploitation, even if working on the most prestigious World Cup projects. While labour laws are slowly being reformed and welfare standards have been introduced, it remains the case that workers can be unpaid for months on end, in full view of the relevant authorities, with little remedy in sight. While it is good news for the QMC workers that they are now beginning to receive some of the money they have long been owed, it should never have taken an Amnesty investigation to get this far, and there remains more to do to make sure workers receive everything they are due.

If the QMC workers are to obtain justice, and if Qatar is to deliver a World Cup that respects human rights and leaves a legacy of improved working conditions, the Qatari authorities, FIFA and the Supreme Committee must all work together to ensure that such a case can never happen again.

In order to remedy the abuses faced by QMC workers:

Qatar Meta Coats, as the subcontracting company directly employing the workers, should remedy all of the abuses by: immediately paying all outstanding salaries and benefits; renewing residence permits; reimbursing recruitment fees; and issuing NOCs to all employees who wish to change jobs.

If QMC is unwilling or unable to provide immediate and full remedy, FIFA, its World Cup partners and companies in the Al Bayt Stadium supply chain should step in and pay them what they are owed.

Ultimately, the Government of Qatar, as the state and therefore the primary protector of human rights, must take timely and efficient actions to protect these workers and redress all the abuses they have suffered.

Moving forward, if migrant workers on World Cup projects and beyond are to be protected from labour abuse and exploitation in Qatar:

The Supreme Committee should fully implement its Workers’ Welfare Standards, ensuring it has a clear means of providing timely remedy when a company is unwilling or unable to do so, including rectifying situations of unpaid wages by paying the workers directly and claiming back the cost of this from contractors.

FIFA should strengthen its human rights due diligence process for the FIFA 2022 World Cup in Qatar and carry out its own independent and regular monitoring of World Cup projects. At the very least it should receive regular updates from its partners on any abuses of human rights. Once abuses directly linked to or associated with the hosting of the World Cup are identified it should be able to mitigate and address them in a timely manner through specific measures put in place.

It must also use its leverage to ensure that Qatar speeds up the reform process and delivers on its promises to end labour abuses and exploitation in the lead up to the 2022 World Cup.

The Government of Qatar should speed up the reform process and completely abolish the kafala system, including by: quickly removing the NOC requirement, effectively implementing the Wage Protection System so it works in a pre-emptive way, speeding up processes at the Committees for the Settlement of Labour Disputes, and providing abused workers with immediate remedy through the Workers’ Support and Insurance Fund.