Maribel (not her real name) was the deputy principal in a state-run primary school in Cuba. She had worked there since graduating, and had been promoted fast.

Before she was ultimately pushed out of her job for her husband’s political activism, which is effectively banned in Cuba, her salary was reduced by half.

The excuse given? She asked her pupils to look up information on the internet for a history lesson. And one of them used Wikipedia.

“They (the government) say children can’t use Wikipedia, because everything in Wikipedia is a lie. (They say) that children have to learn what is in history books, and not look for other information,” she told us when we met her in Mexico’s border town of Tapachula earlier this year.

According to UNESCO, Cuba has one of the most educated populations in the hemisphere. Literacy campaigns have been central to Cuba’s policies since the revolution, and the country’s commendable education system continues to benefit from heavy investment. Yet decades of off-line censorship, and the apparent desire to continue restricting freedom of expression and access to information through a model of online censorship risks undermining Cuba’s historical advances in education.

Cuba’s distinctive model of online censorship

With a constitutional ban on independent private media, Cuba is unique in Latin America. While the independent media scene is transforming, according to a recent report by the Committee to Protect Journalists, a new generation of independent reporters operate in a murky legal environment and under constant threat of arbitrary detentions. They also face major limitations in accessing the internet. A pioneer in this kind of investigative reporting and news commentary is 14ymedio, an online independent daily.

14ymedio’s website is one of those found to be blocked in a report published on 28 August by the Open Observatory of Network Interference (OONI). Using open source (publically available) software, OONI has collected network measures from more than 200 countries across the world. Their aim is to gather facts about how internet censorship is being performed and to assess how the internet works, or doesn’t work, in any given country. OONI’s goal is to increase transparency, and prompt public debates about the legality and ethics of information control, rather than to make political assessments about what they see.

Between May and mid-June 2017, OONI tested 1,458 websites from eight locations across Havana, Santa Clara, and Santiago de Cuba. The list included websites under 30 broad categories. Of these, 1,109 were international sites, mostly from a standard list it uses all over the world for OONI-probe (its testing software for censorship.) They include major mainstream sites of general interest – including Facebook and Twitter. The remaining 349 sites were more specific to the Cuban context.

Of the total number of sites tested, OONI found 41 sites blocked. (OONI tests only a small sample – so many more sites which they didn’t test are also likely blocked).

All the sites blocked had one thing in common. They expressed criticism of the Cuban government, they covered human rights issues, or had to do with circumvention tools (techniques to get around censorship). Blocking internet sites solely to limit political criticism and restrict access to information is – of course – contrary to international human rights law and a violation of the right to freedom of expression.

But this kind of blocking doesn’t only happen on the web in Cuba. According to 14ymedio, Cubacel – the national cellphone network – has been censoring SMS text messages containing the terms “democracy” and “hunger strike”. When graffiti artist and former prisoner of conscience, Danilo Maldonado, was in jail in January this year for painting “Se fue” (He’s gone) on a wall after Fidel Castro’s death, it seems text messages containing “El Sexto” (his artistic name) were also blocked.

According to OONI, the way the webpage blocking is done is “covert”. When users try to access a blocked site, they are redirected to a block page, without an explanation of why the content can’t be accessed. This makes it hard for a user to identify that they are experiencing internet censorship and not some transient network failure or error in loading the page.

Skype is also blocked in Cuba, but using a different kind of technology. For OONI it was something “quite interesting” and not commonly seen, though they have seen something similar in China. Either the government has bought some sophisticated technology they say, or they have some skilled people doing the blocking.

For the technically curious – it has something to do with a re-set package which you can read about more in OONI’s full report. For non-techies, and users, the perceived effect is that Skype works very badly. Most of the time you can’t log in or send messages or see your contact list. But according to OONI, this is “definitely intentional”. And the blocking is being done not by Skype, but from servers probably present in the country.

It has long been reported in the media that Chinese company Huawei is providing the infrastructure services which create the back-bone of the internet and Wi-Fi-hotspots in Cuba. From what they detected inside Cuba, OONI says that it is pretty clear that Chinese contractors developed the software and frontends used for the WIFI hotspot portals. They found Chinese code left behind by them.

Although it makes sense that the government would get the censorship equipment from the same supplier as that rolling out the infrastructure of the internet in Cuba, Amnesty International has not seen any evidence to suggest this is the case.

Despite this, many widely used websites and applications are not blocked – WhatsApp is not. Nor is Facebook. Nor, of course, is Wikipedia.

The big question is why not?

Well, for now, it seems the government doesn’t need to employ sophisticated blocking and filtering.

Dual Internet system

Like its dual currency, Cuba also has a dual internet system. The global internet – unaffordable for most Cubans. And its own intranet – cheaper and highly censored.

The Cuban government controls all the communications infrastructure in the country. (Until 2008, it banned ownership of computer equipment and DVDs). The Internet has long been viewed by the authorities as a “Trojan Horse” for US infiltration, and the US embargo is constantly blamed for Cuba’s poor connectivity. Since the normalization of relations promoted by the Obama administration, and policy changes which have opened possibilities for US telecommunications companies to work in Cuba, this has become a harder argument to sell. And while President Trump’s U-turn in political rhetoric allows the Cuban authorities to revive this excuse, US policy related to the Internet remains largely unchanged.

Instead, in recent years, the Cuban government has prioritized the “digitalization of society.” But that digitalization, it argues, has to “guarantee the invulnerability of the Revolution, the defense of our culture, and the sustainable socialism our people are constructing.”

The government has also set ambitious objectives. In a 2015 strategy, among other things, it said it would connect 50% of homes by 2020. It said that by 2018, entities of the Communist party, organs of the state, banks, and some companies would be 100% connected. By 2020 it said it would have 95% broadband connectivity in educational and health centres and scientific and cultural institutions.

Nevertheless, progress has been slow. In 2014, the national cellphone provider launched Nauta – a mobile e-mail service allowing users to send emails through the government-provided company. In March 2015, the government approved the first public Wi-Fi in Havana and has since opened hundreds of hotspots across the island. Home internet connections were legalized in a pilot program launched only in December 2016. Google Global Cache also placed servers on the island to speed up access to its content in December last year.

But as Cuban authorities continue with the digitalization strategy, the government remains reluctant to put an end to censorship programs. Instead, the government has developed a national internet – a kind of intranet – like the one you might get in a workplace or school in a connected country. Meanwhile, at 1.5 USD an hour, the cost of accessing the World Wide Web remains prohibitive for most Cubans with an average monthly salary of 25 USD, and most only use it to speak with family and friends in the diaspora. Estimates of internet penetration figures vary from 5-40% (depending on the source), but of this percentage many are only likely to be accessing the government-controlled intranet, not the global internet. And interestingly, rates for the intranet have been falling.

What does that mean in practice?

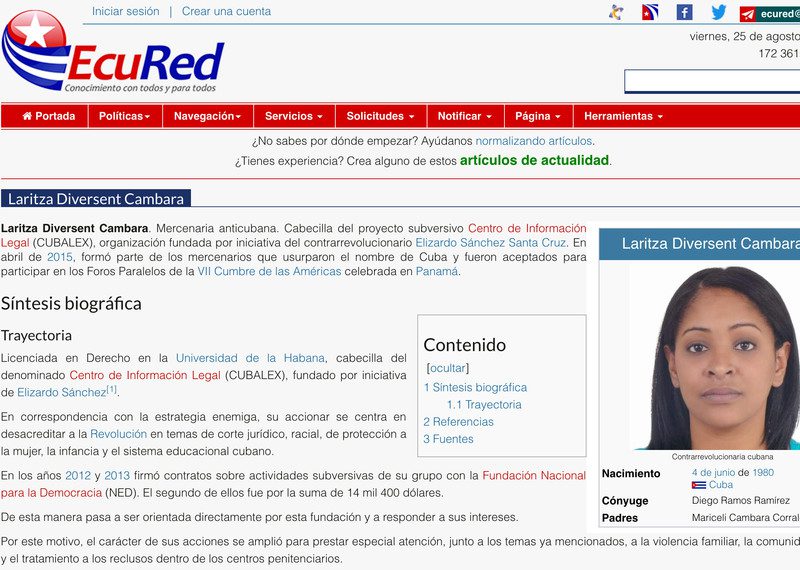

Those that access the national internet experience highly censored, government-curated information. EcuRed, Cuba’s sort-of own version of Wikipedia – an online Cuban encyclopedia – for example, defames human rights defenders. Search for Laritza Diversent Cambara, a human rights lawyer, recently granted asylum in the US along with 12 other members of CUBALEX, Centro de Información Legal, and the site describes her as an “anti-Cuban mercenary” and her organization as “subversive.”

Search for Yoani Sanchez, founder of 14yMedio, and EcuRed describes her a “cyber mercenary”.

Ted Henken, Associate Professor of Sociology at Baruch College, a specialist on Cuba who has published extensively on the media landscape and internet, says “For most Cubans the intranet is a joke, because it’s just a version of (the propaganda) they’ve been getting for 50-60 years but on the internet. It’s out of date, the links are broken.”

And yet this is where it seems the Cuban government wants to invest.

Just days ago, in an apparently leaked video, First Vice President Miguel Díaz Canel, widely expected to be the next President, indicated that the government would shut down OnCuba´s website, calling the site “very aggressive against the revolution.” “Let the scandal ensure. Let them say we censure, it’ fine. Everyone censors,” he said.

In other speeches, has reportedly talked about the need to “perfect our platform” – the national network – and develop work against “subversive projects.” He has also promoted the need to increase access for scientific and educational purposes, and economic reasons. In the same breath he has spoken about the need to generate production of Cuba’s own content, to put “the content of the revolution” online.

Despite the government’s ambitious plans for internet expansion, many Cubans like Maribel say the internet is only available in a limited way in educational settings. She, like other Cubans, says she knows of people who have been expelled from university for accessing “unapproved” information.

Working around “big brother”

Cuban journalists, bloggers and activists have not simply accepted these restrictions. Dozens of emerging digital media projects developed by independent bloggers and journalists (often blocked in Cuba) have found creative workarounds for getting their information published on the global net. Just days ago, 14ymedio published an article called “Recipes for circumventing online censorship.”

Much has also been written about savvy young Cubans who are working around challenges to access and censorship through creative ways of sharing information. Perhaps the most famous innovation is “El Paquete” – pirated Netflix series, videos, music – shared on pen-drives through an island-wide distribution system. Then there’s Streetnet (or SNET), an underground or “bootleg” Internet system built by gamers.

But while these grassroots and spontaneous innovations are exciting, the content in El Paquete or SNET is vanilla. It’s not political in any way.

In order to survive, it (El Paquete) behaves…. They stay out of politics that would get them shut down… You might be discussing Game of Thrones much more than you are discussing the new electoral law

Professor Henken

“In order to survive, it (El Paquete) behaves…. They stay out of politics that would get them shut down… You might be discussing Game of Thrones much more than you are discussing the new electoral law,” says Professor Henken.

Cubans pretty much all believe they are monitored and tracked online and that their private communications are intercepted. ‘That’s normal, everyone knows that,’ is the standard response. After decades of physical surveillance by Committees of the Defense of the Revolution (local members of the communist party who collaborate with state officials and law enforcement agencies), it’s a logical assumption.

Whether it’s the case or not it’s hard to say. Surveillance is notoriously hard to prove. But OONI explains something that is perhaps not immediately obvious. Censorship is an outcome, a sub-set of surveillance.

“When you do internet censorship, what you are effectively doing is implementing surveillence. In order to implement censorship you first need to surveil. You need to know what people are accessing so you can then block it. As we do see internet censorship happening (in Cuba) there must also be surveillance,” OONI told Amnesty International.

And if you think you’re being monitored online you’re even more likely to self-censor.

Cuba’s paradox: Censored education

The Internet is a vital educational tool in the modern world. By acting as a catalyst to free expression, it facilitates other human rights, such as the right to education. It also provides unprecedented access to sources of knowledge, improves traditional forms of schooling, and makes sharing of academic research widely available.

UNESCO and UNICEF have commended Cuba’s educational achievements. Students from across the Caribbean, particularly medical students, graduate from its universities yearly. And yet decades of off-line censorship and this apparent desire to create a Cuban version of reality laden with political ideology through controlled access to the internet undermines this.

Professor Henken describes this simply as “a tragedy.”

Many observers predict Cuba is going to repeat a Chinese model of censorship. OONI’s findings – in a way a “historical archive” of what a network looks like at any moment in time – certainly hint at the potential for more sophisticated blocking and filtering in the future.

But there is another way.

With President Raul Castro expected to step down in 2018, Cuba’s new President will have an opportunity to shape what role the internet plays in Cuba’s future and in its education system.After being pushed out her job, Maribel was eventually offered a job cleaning floors in a kindergarten. Instead she, like tens of thousands of other Cubans last year alone, decided to leave Cuba. And she took the education that made her question the system she lived in with her. She told Amnesty International, “Education is a constant revolution, a constant change. Things have to evolve.”

The government would be wise to listen.