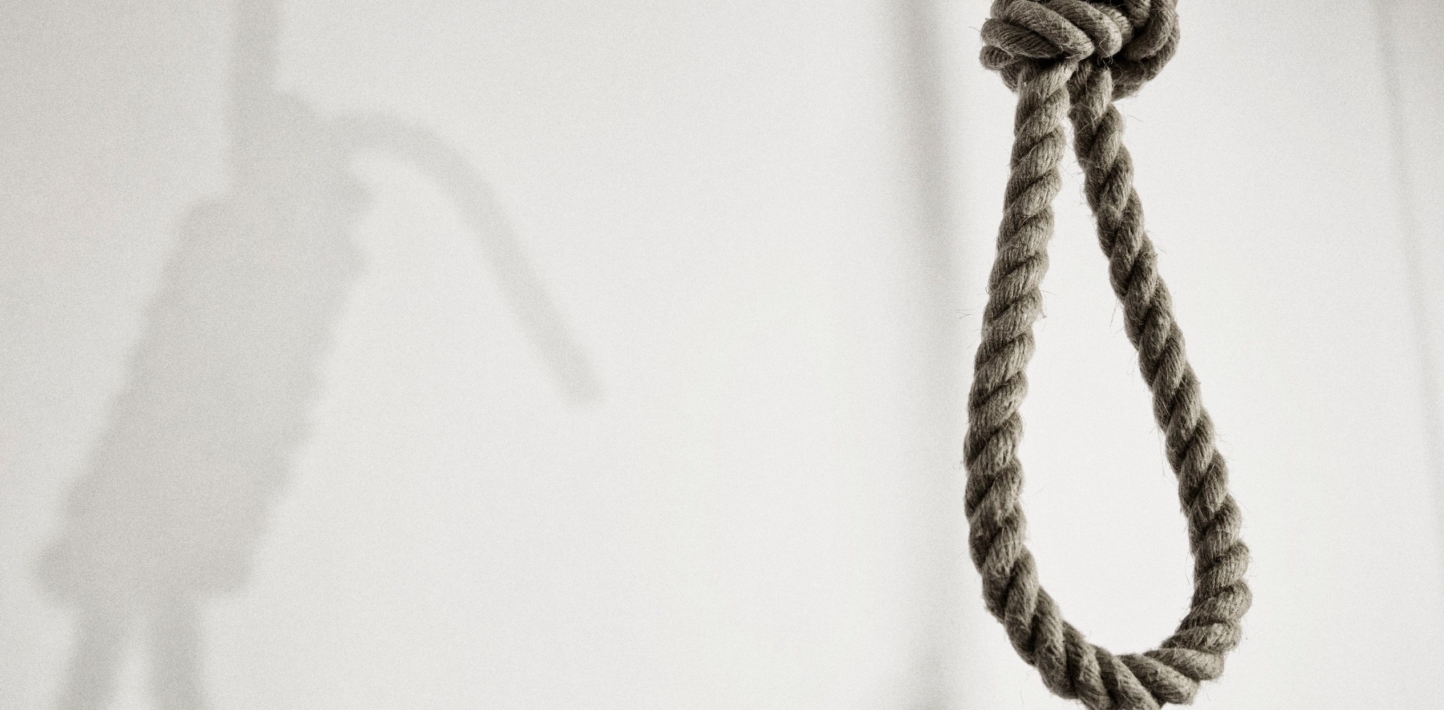

Iranian lawmakers must not miss a historic opportunity to reject the use of the death penalty for drug-related offences and save the lives of thousands of people across the country, said Amnesty International and Abdorrahman Boroumand Foundation today.

In the coming weeks, Iran’s parliament is expected to vote on a bill that amends Iran’s anti-narcotics law, but fails to abolish the death penalty for non-lethal drug-related offences as is required by international law.

“Instead of abolishing the death penalty for drug-related offences, the Iranian authorities are preparing to adopt a deeply disappointing piece of legislation, which will continue to fuel Iran’s execution machine and help maintain its position as one of the world’s top executioners,” said Magdalena Mughrabi, Deputy Director for the Middle East and North Africa at Amnesty International.

The two organizations are calling on Iran’s parliament to urgently amend the proposed legislation to bring it into line with Iran’s obligations under international human rights law, which absolutely prohibits use of the death penalty for non-lethal crimes.

The Iranian authorities are preparing to adopt a deeply disappointing piece of legislation, which will continue to fuel Iran’s execution machine and help maintain its position as one of the world’s top executioners

Magdalena Mughrabi, Deputy Middle East and North Africa Director at Amnesty International

Over the past two years, while this legislation was under discussion, numerous senior Iranian officials publicly conceded that decades of punitive drug policies and rampant use of the death penalty have failed to address the country’s drug addiction and trafficking problems. They have also admitted that drug-related offences are often linked to other social problems such as poverty, drug abuse and unemployment, none of which are solved by executions.

“There’s still time to amend the bill. Iranian lawmakers must listen to the voices of reason and abolish the use of the death penalty for drug-related offences once and for all. A failure to do so would not only run counter to Iran’s stated plans to change course, but would also be a huge missed opportunity to save lives and improve the country’s human rights record,” said Roya Boroumand, Executive Director of Abdorrahman Boroumand Foundation.

The human toll of Iran’s heavy-handed approach to drug control has been devastating. The vast majority of the hundreds of executions carried out in Iran each year are for drug-related convictions. Most of those executed come from the poorest and most vulnerable members of society including Afghans and ethnic and religious minorities. A high-ranking official recently stated that since 1988 Iran has put to death a staggering 10,000 people for drug-related offences.

According to parliamentarians, there are currently an estimated 5,000 people on death row for such offences across the country. About 90% of them are first-time offenders aged between 20 and 30 years old.

An earlier version of the bill, approved by the Judicial and Legal Parliamentary Commission on 23 April 2017, had vastly reduced the scope of the death penalty for drug-related offences. Between April and June, members of the commission tried to repeatedly schedule the bill for a vote but said they failed to do so due to opposition from security bodies overseeing Iran’s anti-narcotics programmes.

Eventually, in July, they introduced multiple regressive amendments to the bill. Some members of parliament said in media interviews that they made these amendments after immense pressure from Iran’s judicial and law enforcement officials as well as the country’s Drug Control Headquarters.

The latest version of the bill, like Iran’s current anti-narcotics law, maintains the death penalty for a wide range of drug trafficking offences based on the quantity and type of drugs seized. However, it proposes to increase the quantities of drugs required for imposing the death penalty.

Under Iran’s current laws, the death penalty is imposed for trafficking more than 30g of heroin, morphine, cocaine or their chemical derivatives or more than 5kg of bhang, cannabis or opium. The proposed law increases this quantity to 2kg for heroin, morphine, cocaine or their chemical derivatives and more than 50 kg for bhang, cannabis or opium.

The choice between life or death should not come down to a crude mathematical calculation based on a quantity of drugs seized from an individual

Roya Boroumand, the Executive Director of Abdorrahman Boroumand Foundation

“Though this law, if implemented properly, may contribute to a drop in the number of executions, it will still condemn scores of people every year to the gallows for offences that must never attract the death penalty under international law,” said Magdalena Mughrabi.

“The death penalty is a cruel, inhuman and degrading punishment and its use is abhorrent in any situation. The choice between life or death should not come down to a crude mathematical calculation based on a quantity of drugs seized from an individual,” said Roya Boroumand.

Amnesty International and Abdorrahman Boroumand Foundation call on the international community, particularly the EU, to urge Iran to amend the bill to abolish the death penalty for all drug-related offences. The

Iranian authorities must move towards a criminal justice system that is focused on rehabilitation and treats prisoners humanely.

Background:

Amnesty International has collaborated with Abdorrahman Boroumand Foundation to record Iran’s execution figures. As of 26 July 2017, Amnesty International and Abdorrahman Boroumand Foundation have recorded 319 executions, including 183 for drug-relatedoffences. In 2016, at least 567 people were executed, of which 328 were for drug-related offences.

Efforts to amend Iran’s anti-Narcotics law first began in 2015, when 70 members of parliament proposed a bill to abolish the death penalty for all drug-related offences except those involving armed trafficking. This bill was halted after it was deemed unconstitutional. In 2016, efforts to amend the legislation were renewed. These culminated in a draft bill finalized in April 2017, which proposed replacing the death penalty with up

to 30 years’ imprisonment for all drug-related offences, except those that: involved the use of arms; involved the recruitment of under 18-year-olds; or were committed by the leader of an organized criminal network or an individual who had been previously sentenced to death, or more than 15 years in prison.

Although this version of the bill still fell short of Iran’s international human rights obligations, it raised great hopes that the number of people sentenced to death and executed every year for drug-related offences would be significantly reduced.