WARNING:

This report contains descriptions of violence against women.

Women have the right to use Twitter equally, freely and without fear.

But Twitter’s inadequate response to violence and abuse against women is leading women to self-censor what they post, limit or change their interactions online, or is driving women off the platform altogether.

At times, the threat of violence and abuse against women on Twitter, alone, leads to a chilling effect on women speaking out online.

The silencing and censoring impact of violence and abuse against women on Twitter can have far-reaching and harmful repercussions on how younger women, women from marginalized communities, and future generations fully exercise their right to participate in public life and freely express themselves online.

There are many women, and many women of colour, who don’t participate online in the way that they would want to because of online abuse.

Diane Abbott, UK Politician and Shadow Home Secretary

Has experiencing abuse on twitter made you change the way you use the platform?

Why Violence and Abuse against Women on Twitter is a Freedom of Expression Issue

Ensuring that everyone can freely participate online and without fear of violence and abuse is vital to ensuring that women can effectively exercise their right to freedom of expression.

The rights to freedom of expression and to non-discrimination are guaranteed under major international human rights instruments including the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights.

The United Nations Human Rights Council has stated that “the same rights people have offline must also be protected online, in particular freedom of expression, which is applicable regardless of frontiers and through any media of one’s choice, in accordance with articles 19 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights”.

Additionally, in a joint-statement, the United Nations experts on Freedom of Expression and Violence against Women, respectively, commented on the negative impact of online abuse on the right to freedom of expression online for women. Special Rapporteur on Freedom of Expression, David Kaye states,

“The internet should be a platform for everyone to exercise their rights to freedom of opinion and expression, but online gender-based abuse and violence assaults basic principles of equality under international law and freedom of expression. Such abuses must be addressed urgently, but with careful attention to human rights law”.

UN Special Rapporteur on Violence against Women Dubravka Simonoci adds,

“Ensuring an internet free from gender-based violence enhances freedom of expression as it allows women to fully participate in all areas of life and is integral to women’s empowerment”.

Many of the women interviewed by Amnesty International described changing their behaviour on the platform due to Twitter’s failure to provide adequate remedy when they experienced violence and abuse. The changes women make to their behaviour on Twitter ranges from self-censoring content they post to avoid violence and abuse, fundamentally changing the way they use the platform, limiting their interactions on Twitter, and sometimes, leaving the platform completely.

Amnesty International’s online poll about women’s experiences of abuse on social media platforms confirmed that the experiences of women interviewed in this investigation are a reflection of the silencing and censoring impact of online abuse on women more generally. It found that of the women polled who experienced online abuse or harassment, between 63% and 83% women in the eight countries polled made some changes to the way they used social media platforms, with the figures for the USA and UK being 81% and 78% respectively.

The specific ways in which women modified their online interactions after experiencing abuse or harassment varied from women increasing privacy and security settings to women making changes to the content they post.

However, the number of women who made changes to the posting or sharing of expression or opinions is deeply troubling. Amnesty International’s online poll showed that across the 8 countries polled, 32% of women who experienced abuse or harassment online said they had stopped posting content that expressed their opinion on certain issues, including 31% of women in the UK and 35% of women in the USA.

Limiting Interactions and Changing Behaviour

For many women, using Twitter is not easy; it means adapting their online behaviour and presence, self-censoring the content they post and limiting interactions on the platform out of fear of violence and abuse.

For example, Scottish Parliamentarian and Leader of the Opposition Ruth Davidson told Amnesty International about how an influx of abuse can change the way she uses the platform. She explains,

“…The sheer volume of abuse can make you sometimes feel hunted online. At that point you just stop reading the mentions and you use it as a transmit function rather than a transmit and receive platform.”

US journalist and writer Jessica Valenti told Amnesty International that although security features like ‘block’ and ‘mute’, as well as modifying Twitter notifications, have helped filter out abuse, it also means the platform and the way she uses it has fundamentally changed the way she interacts.

“Twitter has a thing where you can turn off notifications from anyone you don’t follow back. It’s a good thing and a bad thing. It’s vastly improved my day to day experience, but it’s bad in terms of I don’t actually get to hear from my readers, so that sucks.”

Women, like US journalist Imani Gandy, also stressed to Amnesty International how violence and abuse against women on the platform simply becomes normalized after a while. Imani states,

“The abuse I receive on Twitter is mostly filtered out and I have trained myself to not search my name because then I get really angry. I’ve been online for 8 years and political on Twitter for 7 years so after 7 years I guess you just get used to it…it has become a part of my life, which is kind of sad, I guess. The filtering on my part and using third party apps have made it better but I’m also trying to reduce my time on Twitter as well.”

For many women, the inability to fully participate and express themselves equally online means that they are absent from public conversations they would like to be part of, and sometimes, need to be part of. To not engage or comment on an issue out of fear of violence and abuse means that certain women’s voices are not represented on Twitter and that women are no longer part of the debate. For women in the public eye, in particular, this can have a detrimental effect on their career and building networks. The silencing effect of online abuse on women, including on Twitter, may also send a worrying message to younger generations that women’s voices are not welcome.

Self-Censorship to Avoid Abuse

Many of the women who spoke to Amnesty International stressed that freely expressing themselves on Twitter is not worth the risk of violence and abuse.

UK activist Alex Runswick told Amnesty,

“The abuse has made me much, much more reluctant to comment on things. I mean, I still do tweet sometimes, but I think about it very, very careful before I do. Recently there was a case in the media about comments a judge had made in a rape case…and I was just thinking, okay, I want to tweet about this. And then I actually sat down for five minutes and had a conversation with my husband and said ‘Do I tweet this or not’ knowing full well what the response would be…”

US writer and presenter Sally Kohn echoed similar sentiments. She said,

“Once in a while there will be a tweet that I think I want to send and I’ll go, ‘Oh no, it’s not worth the trolls’.”

UK activist Sian Norris recalled a time that she posted a tweet on Transgender Day of Remembrance but took it down a few minutes later. She explained,

“I had posted something like ‘Today we remember transgender women being killed by male violence’. Within minutes around 5 accounts all with really horrible naked pictures of a man in the profile photo retweeted it. The re-tweets didn’t say anything but just had a really confrontational account photo and so I deleted my tweet. I was cross because it was an important day and I should be able to send solidarity.”

UK journalist Allison Morris explained to Amnesty International how she no longer posts about topics that she would have tweeted about in the past.

“First off, I don’t get Twitter notifications on my phone, I don’t want to see them. Also, I definitely self-censor what I post. There are things that I don’t tweet about even though I would have a couple of years ago. I think it’s just not worth the hassle, it’s not worth the abuse, and it’s not worth having to deal with hundreds of people all piling in and re-posting and re-tweeting it.”

Others talked about the time and energy they spend in carefully crafting and curating their Twitter posts to minimize the risk of violence and abuse on the platform.

UK poet and actor Travis Alabanza told Amnesty,

“I think before every tweet I send. Every single tweet now – it’s all completely crafted. My online persona is always crafted but now it’s to the point that there is nothing real about my Twitter anymore…

I stay well clear of trans stuff most of the time. And if I’m going to bring up trans things now, I preface it so much in a thread, and as soon as I see it gain traction I look and decide whether or not I want it, and if I don’t, I delete. Before I would say I was far more political online and that’s what I was getting known for. Now I’ve moved a lot of this onto another social media platform. Everything about my Twitter now is just heavily constructed.”

US games developer Zoe Quinn faces a similar process every time she thinks about posting on Twitter. She explains,

“I have to think three times about everything I post on Twitter. A lot of it relies on how ‘fuck it’ I’m feeling that day – which is exhausting. I also have to be very careful about who I visibly support online. If they haven’t been briefed on what me giving them a platform or visibility means [in terms of potential abuse], it is kind of unfair to them. People have set up bots to archive everything that I do and I’m not sure everyone is prepared to handle [the level of abuse I’m used to].”

Women Leaving Twitter

The silencing impact of violence and abuse against women on Twitter manifests in different ways for different women online. Although the degree to which women are silencing themselves may differ, the impact of violence and abuse on the right to freedom of expression is a cause for concern not only for Twitter, but society more widely.

In July 2017, UK Member of Parliament and Shadow Home Secretary, Diane Abbott, told Amnesty International, “Well the abuse that I get online does to a degree limit my freedom of expression. In terms of Twitter, I now spend much less time on Twitter than I used to because the abuse is so terrible.” More recently in January 2018, she commented,

“I hardly go on Twitter any more…It’s a shame really, I used to enjoy Twitter.”

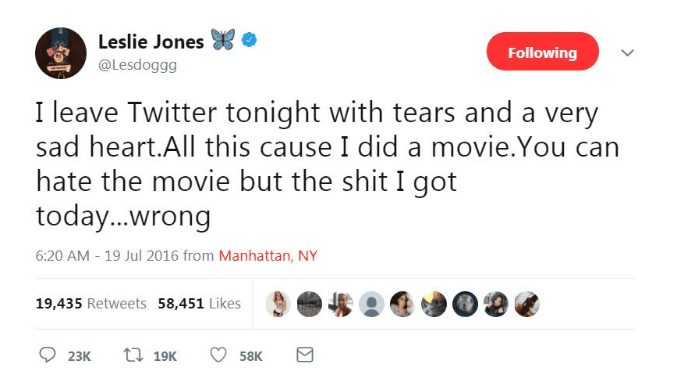

In recent years Twitter has been plagued with high-profile women leaving the platform after experiencing violence and abuse. For many, this is not an easy decision but seems to be the only option given the company’s failure to adequately tackle this issue and provide appropriate remedies. In August 2016, US actor Leslie Jones temporarily left Twitter after a wave of racist abuse on the platform following the release of the film Ghostbusters 2. In January 2017, US journalist Lindy West wrote an op-ed about leaving the platform after years of enduring violence and abuse on Twitter.

US writer Chelsea Cain told Amnesty International about her decision to temporarily leave Twitter after experiencing abuse on the platform. She recounted,

“I had written a comic book called Mockingbird – a series – and the cover of the last issue featured the character wearing a shirt that says, ‘Ask Me About My Feminist Agenda.’ I knew it was provocative. That was the point. But I was surprised at the level of hysteria. Let’s just say that not everyone appreciated my feminist gesture, and most of them had Twitter accounts.

I posted something on Twitter about my intention to delete my account. Then I left my computer and watched an episode of Buffy with my daughter, which seemed like a far better use of my time. I didn’t go back online until the next morning. By then Twitter had exploded. So many comments were appearing in my feed that they were coming and going faster than I could read them. I deleted my account, closed my laptop, backed away, went out the front door, and kept walking. It was like leaving a burning house.”

US abortion rights activist Renee Bracey Sherman also explained how she left Twitter and other social media platforms following the wave of abuse and violence she received after writing an open letter in media outlet Refinery 29. She told us,

“The harassment on Twitter lasted two to two and a half weeks. I was dealing with so much hate and I had never experienced so much. Someone tweeted at me saying they hoped I would get raped over and over again…that’s when I was like this isn’t the normal shit I am used to…I threw my phone under the couch and hid in bed. I left social media for 6 weeks.”

US journalist and writer Jessica Valenti spoke about her experience of leaving Twitter after someone posted a rape threat against her daughter on another platform. She explained,

“Someone posted ‘I’m going to rape and gut your daughter’…It was a breaking point for me and I needed to step back. I needed to take stock of what I wanted to do and I needed some space to be able to do that.”

UK journalist Vonny Moyes also spoke about the need to leave Twitter when abuse or violence against her becomes too much to handle. She told us,

“I’m being really disciplined about self-care and taking time out to re-charge my batteries so I deactivate Twitter for a few days. Or maybe a week at a time. Even last weekend, I had a steady drip of harassment and dismissiveness on Twitter so I thought ‘Let’s get out of the city, go to the beach and turn off our phones’…it’s crazy that I have to do all these things in my offline life to balance out the effects of being online. It’s really elbowed its way into my – I don’t want to say ‘real’ life – because my digital life is my real life. It’s everyone’s real life now.”

Impact of Violence and Abuse on Women’s Participation in Public Life

Ensuring the Internet is free from violence and abuse against women enhances freedom of expression and allows women to participate on an equal basis in public life. US activist Pamela Merritt talked to Amnesty International about the importance of women staying online. She told us,

“I think it is so important that women, and women of colour, particularly, stay online. It’s important that we create our own spaces where we can be safe and share ideas. We should see this harassment for what it is: an extension of the patriarchy and oppression. The goal of online harassment is to erase women and women of colour from the public dialogue. So the internet is a space where we are having an impact and that is where the harassers want to silence us.”

The UN Special Rapporteur on Violence against Women warns that online violence and abuse,

“can lead women and girls to limit their participation and sometimes withdraw completely from online platforms”.

UK writer and activist Laura Bates re-iterated these concerns. She explains,

“We are seeing young women and teenage girls experiencing online harassment as a normal part of their existence online. Girls who dare to express opinions about politics or current events often experience a very swift, misogynistic backlash. This might be rape threats or comments telling them to get back in the kitchen. It’s an invisible issue right now, but it might be having a major impact on the future political participation of those girls and young women. We won’t necessarily see the outcome of that before it’s too late.”

Laura Bates’ words were echoed by young women. Rachel*, a 19-year-old woman in the UK without a large Twitter following, told Amnesty,

“The main thing that goes through my head every time I tweet anything feminist in nature is I’ll probably get death threats if this gets any traction. It’s sad and depressing to think that every time you tweet something opinionated it may come back with something horrible. Being online should be somewhere you feel safe, if you can’t feel safe on your Twitter account – then what’s the point? Sometimes I feel like just leaving Twitter”.

A report by the National Democratic Institute highlights just how serious the silencing and censoring impact of violence and abuse against women online can be. It states,

“By silencing and excluding the voices of women and other marginalized groups, online harassment fundamentally challenges both women’s political engagement and the integrity of the information space….In these circumstances, women judge that the costs and danger of participation outweigh the benefits, and withdraw from or choose not to enter the political arena at all”.

This was also a particular concern for female politicians interviewed by Amnesty International. Former UK Politician Tasmina Ahmed-Sheikh summed up her concerns by saying,

“If online abusers are not held to account, if they are not reported, if we don’t do that, then young women are not going come forward, young women from minority communities are not going to come forward, disabled people are not going to come forward, people from LGBTI communities are not going to come forward, and then what kind of society are we going to be? What will our Parliament look like?”

First Minister of Scotland Nicola Sturgeon, raised a similar worry about the impact of online abuse against women in politics deterring a future generation of leaders from entering politics. She explains,

“What makes me angry when I read that kind of abuse about me is, I worry about that it’s putting the next generation of young women off politics. So, I feel a responsibility to challenge it, not so much on my own behalf, but on behalf of young women out there who are looking at what people say about me and thinking ‘ I don’t ever want to be in that position’.”

It is imperative that Twitter respects the right of all women to exercise their human rights online, including the right to freedom of expression. A failure to do so will have serious consequences for women’s participation in public life now and in the generations to come.

As UK Politician and Shadow Home Secretary Diane Abbott points out,

“I think the online abuse I get makes younger women of colour very hesitant about entering the public debate and going into politics. And after all, why should you have to pay that price for being in the public space?”