The New York City Police Department (NYPD) has the ability to track people in Manhattan, Brooklyn and the Bronx by running images from 15,280 surveillance cameras into invasive and discriminatory facial recognition software, a new Amnesty International investigation reveals.

Thousands of volunteers from around the world participated in the investigation, tagging 15,280 surveillance cameras at intersections across Manhattan (3,590), Brooklyn (8,220) and the Bronx (3,470). Combined, the three boroughs account for almost half of the intersections (47%) in New York City, constituting a vast surface area of pervasive surveillance.

Surveillance City

Full heat map is available here.

“This sprawling network of cameras can be used by police for invasive facial recognition and risk turning New York into an Orwellian surveillance city,” says Matt Mahmoudi, Artificial Intelligence & Human Rights Researcher at Amnesty International.

“You are never anonymous. Whether you’re attending a protest, walking to a particular neighbourhood, or even just grocery shopping – your face can be tracked by facial recognition technology using imagery from thousands of camera points across New York.”

Most surveilled neighbourhood

East New York in Brooklyn, an area that is 54.4% Black, 30% Hispanic and 8.4% White according to the latest census data, was found to be the most surveilled neighbourhood in all three boroughs, with an alarming 577 cameras found at intersections.

The NYPD has used facial recognition technology (FRT) in 22,000 cases since 2017 — half of which were in 2019 alone. When camera imagery is run through FRT, the NYPD is able to track every New Yorker’s face as they move through the city.

FRT works by comparing camera imagery with millions of faces stored in its databases, many scraped from sources including social media without users’ knowledge or consent. The technology is widely recognized as amplifying racially discriminatory policing and can threaten the rights to freedom of peaceful assembly and privacy.

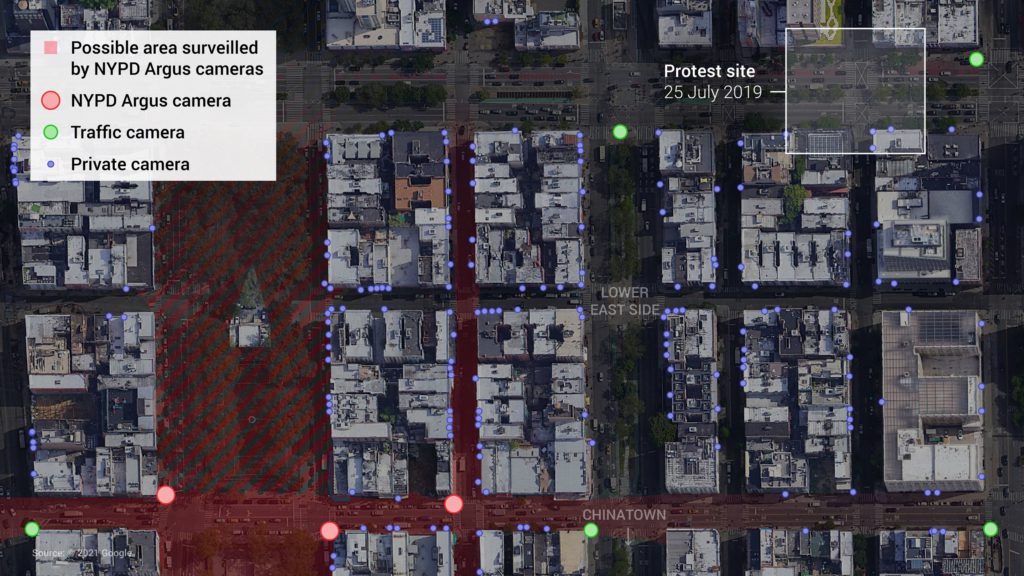

Amnesty International research has modelled the extensive field of vision of New York’s CCTV network. For example, the intersection of Grand Street and Eldridge Street sits near the border of Chinatown and was near a key location in the Black Lives Matter protests. Our investigation found three NYPD-owned Argus cameras around the site, in addition to four other public cameras and more than 170 private surveillance cameras, which our modelling suggests have the capacity to track faces from as far as 200 metres away (or up to 2 blocks).

Supercharging racist policing

In the summer of 2020, facial recognition was likely used to identify and track a participant at a Black Lives Matter protest, Derrick ‘Dwreck’ Ingram, who allegedly shouted into a police officer’s ear. Police officers were unable to produce a search warrant when they arrived at his apartment.

Amnesty International, and coalition partners of the Ban the Scan campaign, submitted numerous Freedom of Information Law (FOIL) requests to the NYPD, requesting more information about the extent of facial recognition usage in light of Dwreck’s case. They were dismissed, along with a subsequent appeal, while some are being litigated.

“There has been a glaring lack of information around the NYPD’s use of facial recognition software – making it impossible for New Yorkers to know if and when their face is being tracked across the city,” says Matt Mahmoudi.

“The NYPD’s issues with systemic racism and discrimination are well-documented – so, too, is the technology’s bias against women and people of colour. Using FRT with images from thousands of cameras across the city risks amplifying racist policing, harassment of protesters, and could even lead to wrongful arrests.”

“Facial recognition can and is being used by states to intentionally target certain individuals or groups of people based on characteristics, including ethnicity, race and gender, without individualized reasonable suspicion of criminal wrongdoing.”

Global effort

More than 5,500 volunteers have participated in the investigation, launched on 4 May 2021 as part of the innovative Amnesty Decoders platform. The project is ongoing to collect data on the remaining two New York boroughs, but already volunteers have analysed 38,831 locations across the city.

It was a global effort – volunteers from 144 countries participated, with the largest group of volunteers (26%) being in the United States. In just three weeks, volunteers contributed an eye-watering 18,841 hours – more than 10 working years for a researcher working full time in the USA. Participants were given Google Street View images of locations around New York City and asked to tag cameras, with each intersection analysed by three volunteers. The total figures include a mix of both public and private cameras, both of which can be used with FRT.

Methodology

Data collection

The data for Decode Surveillance NYC was generated by several thousand digital volunteers. Volunteers participated via the Amnesty Decoders platform, which uses microtasking to help our researchers answer large-scale questions.

For Decode Surveillance NYC volunteers were shown a Google Street View panorama image of an intersection and asked to find surveillance cameras. In addition, we asked volunteers to record what cameras were attached to. Volunteers were presented with three options: 1, street light, traffic signal or pole; 2, building; 3, something else. If they selected “street light, traffic signal or pole”, they were asked to categorize the camera type as: 1, dome or PTZ; 2, bullet; 3, other or unknown.Volunteers were supported throughout by a tutorial video, visual help guide, and moderated forum. On average each volunteer took 1.5 minutes to analyze an intersection.

Data analysis

Information about what the camera was attached to and its type was used as a proxy for public or private ownership. For the purposes of the research it was assumed that cameras attached to buildings were likely to be privately owned. Cameras, such as dome cameras, attached to street lights, traffic signals or roadside poles, were most likely to be owned by a government agency with the permission and access to install them.

Each intersection was evaluated by three volunteers. The data published on 3 June 2021 is the median camera count of these three evaluations per intersection. We chose to use the median as it is least susceptible to outliers and individual errors, leveraging the “wisdom of the crowd”. Counts were normalized by the number of intersections within each administrative unit to account for different surface areas.

Our data science team also used a qualitative review of a subset of intersections by an expert to look for systematic errors or biases, such as volunteers tagging only one of two cameras on NYPD Argus boxes.

This preliminary analysis ensures correct orders of magnitude, sufficient for early conclusions. Finer-grained analysis will follow, including bootstrapped confidence intervals. We will also assess quality metrics such as precision and recall to compare the decoders’ aggregation to expert judgement on a small representative subset of intersections.

3D modelling

3D modelling was used to demonstrate the estimated distance from which an NYPD Argus camera could capture video footage processable by facial recognition software.

In the absence of technical specifications for the NYPD Argus cameras, we researched commercial models. According to historical Google Street View imagery, the camera we modelled was installed between November 2017 and June 2018. Data on commercial cameras available at the time suggest that it is likely to be a Pan, Tilt, and Zoom (PTZ) model containing a 6–134 mm varifocal lens able to film at 4K or 8 megapixel resolution.

The 3D model shows that the camera could potentially monitor neighbouring roads and capture faces in high definition from as little as few metres to up to 200 metres (or two blocks) away.

For more information about the project, log into Decode Surveillance NYC to see the Help Guide. Decode Surveillance NYC was scoped and designed with past camera mapping projects in mind, such as the 1998 and 2006 walking surveys conducted by New York Civil Liberties Union (NYCLU).