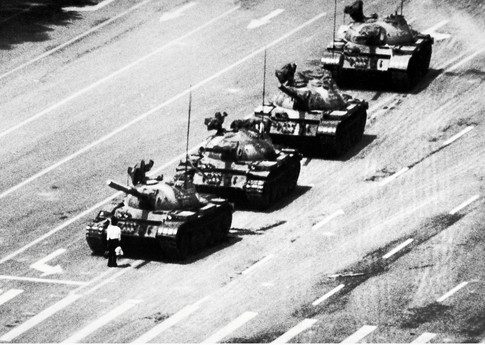

It is one of the most iconic moments in the fight for freedom in recent history. A lone man, holding a shopping bag in each hand, stands defiantly in front of a row of mighty military tanks close to Beijing’s monumental Tiananmen Square. Then, with cameras capturing the moment for broadcast around the world, he raises his right hand to signal the tanks to stop. And, for a brief moment, they do.

What made this man’s act of resistance even more remarkable was the horror that the world had witnessed just the day before.

On the evening of 3–4 June 1989, Chinese tanks rolled into Tiananmen Square to brutally crush an unprecedented democracy movement. Hundreds, possibly thousands, of people were killed when troops opened fire on the students and workers who for weeks had been peacefully calling for political reforms.

No one knows the exact number because three decades on the authorities in China continue to do all they can to stop people from asking questions about that day or even talking about it.

In the days that followed the bloody crackdown, the Chinese authorities issued a list of 21 individuals “wanted” for their role in organizing the protests.

Number One on that list was Wang Dan, who went on to spend six years in prison.

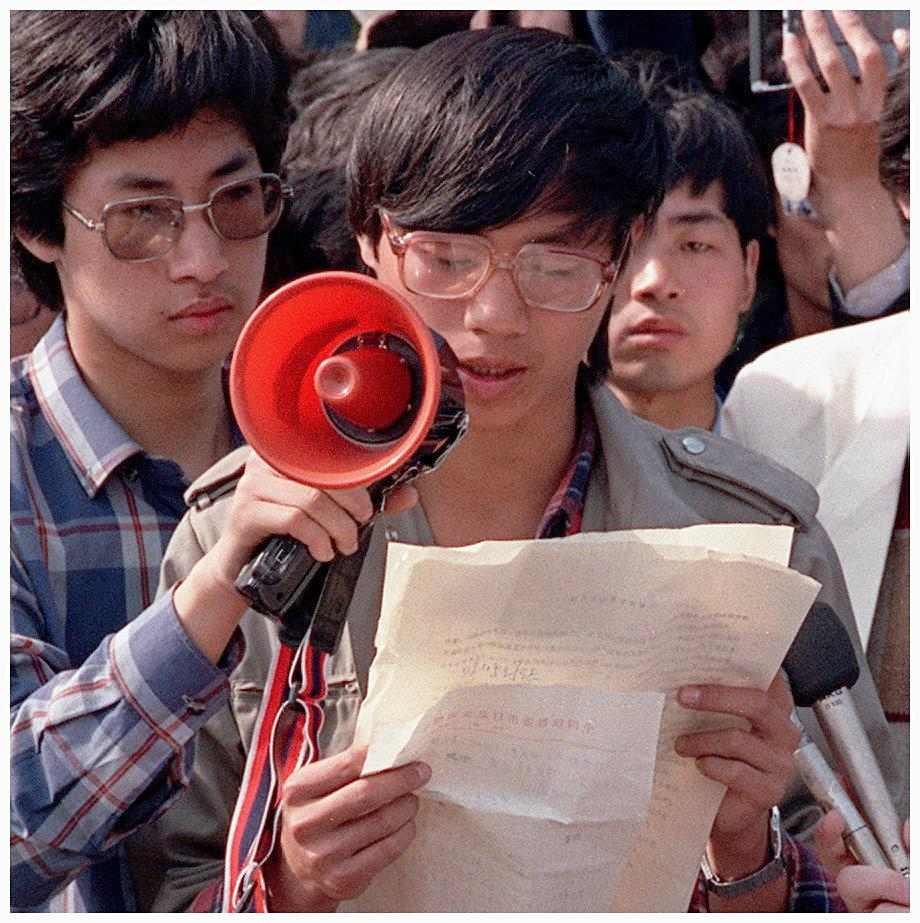

Before it happened, in the spring of 1989, Wang was a 20-year-old student at Peking University, where he organized talks on democracy.

We cared about our political future. We never expected the government would send in the troops against their own people. We thought they only wanted to frighten us.

Wang Dang, as a student leader in 1989 played a key role in the protests.

“I was only one of [many] leaders during the movement. I don’t know why I was Number One on the list,” he recalled.

“We were a generation concerned about the political situation. We cared about our political future. We never expected the government would send in the troops against their own people. We thought they only wanted to frighten us.”

When troops opened fire on the night of 3 June, Wang Dan was in his university dorm.

“My classmate called from somewhere near Tiananmen Square. He told me: ‘The crackdown has started. People have died.’ I tried to go to Tiananmen, but the police had blocked the highway.

“I was in shock,” remembered Wang. “For three or four days I couldn’t say anything.”

For several weeks, friends helped Wang Dan to hide, but the authorities tracked him down on 2 July.

Wang served nearly four years in prison before his release in 1993. He could have left China then but decided to stay.

“I wanted to continue my fight. For the people that died it was my obligation to do something more. I still saw there was the possibility of change. That’s why I chose to stay.”

Less than two years later, Wang Dan was back in jail but this time with an 11-year sentence.

He was released after two years on medical parole on the condition he go into exile.

I’ll never regret what happened. For our future we need to make sacrifices. I never feel regret. It was a big enlightenment; democracy touched the soul of Chinese people.

Wang Dan on China's 1989 democracy movement

“It was a difficult decision to leave. It was very hard, knowing I wouldn’t see my family. But if I refused to leave I would stay in jail. I wouldn’t have been able to do anything there.”

Wang Dan went on to study at Harvard and Oxford and now lives in the US after teaching politics at a university in Taiwan for several years.

No regrets

“If I was still in China I could do nothing. I’d be followed by the police and would not be able to contact people. Outside China at least I can speak freely,” he said.

“I’ll never regret what happened. For our future we need to make sacrifices. I never feel regret. It was a big enlightenment; democracy touched the soul of Chinese people.”

One of those people was Lü Jinghua.

I heard bullets whizz past and people getting shot. One body fell by me, then another. I ran and ran to get out of the way. People were crying out for help, calling out for ambulances. Then another person would die.

Lu Jinghua recalls the horror of when troops opened fire on protesters late on 3 June 1989

Her life also changed forever in the spring of 1989. She was 28 years old at the time and used to make a living selling clothes at a small stall in China’s capital.

After seeing the students protesting at Tiananmen Square over several days, she decided to approach them to find out more about their campaign. A few days later she started bringing them water and, eventually, she joined them.

“I volunteered to be a broadcaster because of my voice. I would stand in Tiananmen Square and share the latest news over the loudspeakers. At night I would sleep in a tent at the square,” she said.

“I really enjoyed those days. I was happy. The movement changed my life.”

But things soon took a dark turn. She was at the square when the tanks rolled in.

“I heard bullets whizz past and people getting shot. One body fell by me, then another. I ran and ran to get out of the way. People were crying out for help, calling out for ambulances. Then another person would die.”

That was only the start of her nightmare.

After the crackdown Lü Jinghua was put on the “most wanted” list and her family was violently harassed by the authorities. She was left with no choice but to flee Beijing, leaving her young baby behind.

“It was an impossible decision. But I needed to save my life and that’s why I accepted I had to go.”

After a dangerous journey swimming up a river and taking a small boat, she reached Hong Kong and then flew to New York.

We will never forget what happened. It was the right thing to do. I was young, doing something. I still believe in this. I still fight for human rights in China.

Lu Jinghua on the 1989 democracy protests.

In 1993, she attempted to return to China to see her family: “When I got off the plane the authorities stopped me. I could see my mum holding my daughter on the other side of the gate, but the police wouldn’t let me talk to them.”

Lü’s daughter was eventually able to join her in the USA in December 1994 but Lü was never allowed back into China, not even to attend her parent’s funerals.

But Lü Jinghua has no regrets.

“We will never forget what happened. It was the right thing to do. I was young, doing something. I still believe in this. I still fight for human rights in China.”