For more than sixty years Colombia’s history has been marked by armed conflict rooted in territories where a state presence seems non-existent.

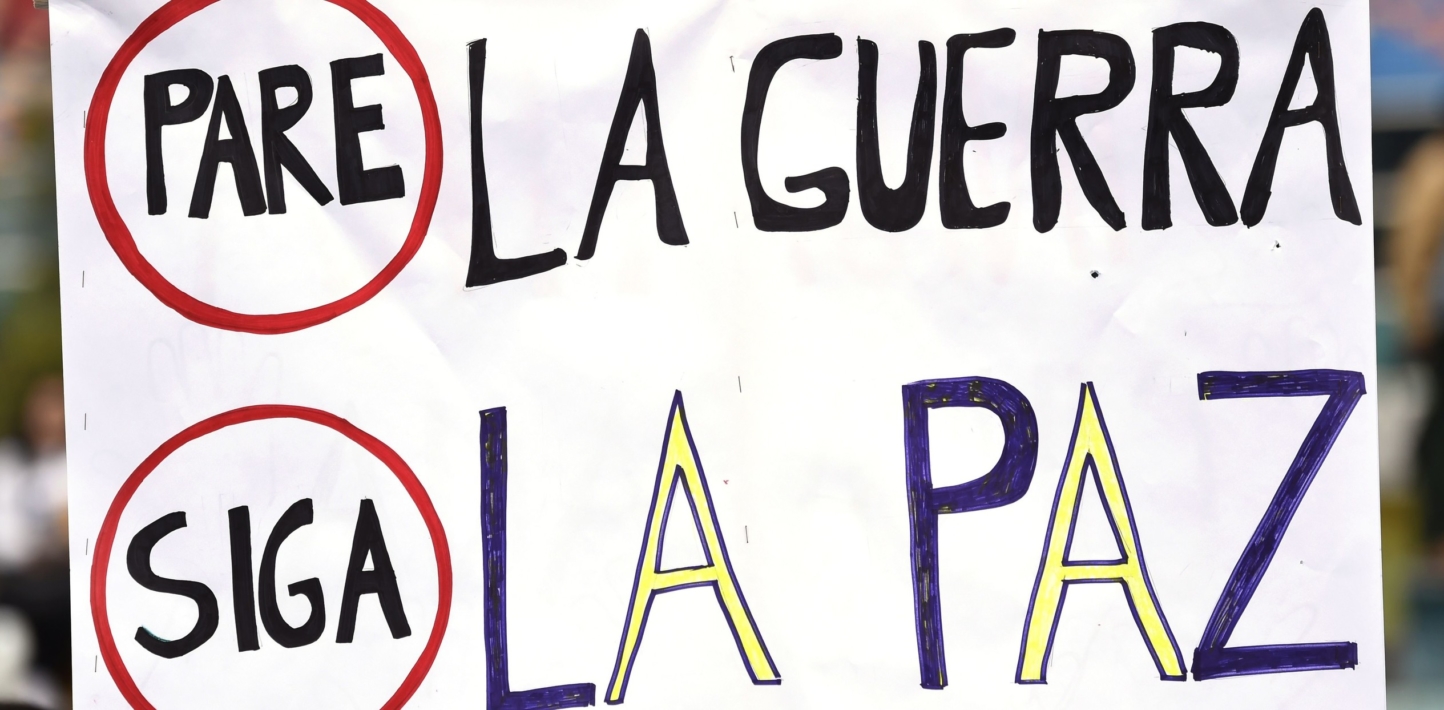

In November 2016, this history took a hopeful turn for communities that have endured the violence. A door was opened for the country to start a process aimed at writing a new history. The whole world celebrated (and still celebrates) the efforts to negotiate an end to Latin America’s longest running armed conflict. The ceasefire could mean a major breakthrough in guaranteeing human rights in Colombia.

The signing of a Peace Agreement between the Colombian state and the FARC-EP guerrillas has saved lives, though this agreement is not without shortcomings. The numbers point to a considerable decrease in deaths in combat over the past year and a half.

Nevertheless, for the victims of this conflict, the real triumph will be to avoid repetition of the history of bloodshed, suffering and abandonment that has marked their lives. To this effect, more than 9,000 weapons have been handed over and a humanitarian landmine removal process has been initiated in 188 municipalities. More than twelve bodies have been created to implement this process, one of which is the Truth Commission (Comisión de la Verdad).

These advances have meant initiating a long process; one which should not lose sight of what millions of victims demand: guarantees of non-repetition

Erika Guevara Rosas, Americas Director at Amnesty International

These advances have meant initiating a long process; one which should not lose sight of what millions of victims demand: guarantees of non-repetition.

On another note, the current landscape is worrying and the human rights crisis continues to be a constant in Colombia. Just in the first half of this year, the Ombudsman’s Office has recorded that more than 17,000 people have been victims of forced displacement in the country, resulting from the rearranging of armed actors on their territories. Forced displacement – which is a crime under international law – and land dispossession continue to mainly affect Indigenous and Afro-descendent communities, under the impassive eye of an unresponsive state.

At the same time, the number of targeted killings of human rights defenders in the country is harrowing. People who exercise leadership in their communities continue to be killed on a daily basis, especially those who defended the implementation of the Peace Agreement, or that support land restitution processes and the rights of the armed conflict’s victims. Comprehensive responses have yet to arrive. Violence against women, especially sexual violence committed by armed actors, has increased under a cloak of silence and impunity.

Beyond the current political discussions, the Colombian state must focus on guaranteeing the rights of armed conflict victims to justice, truth, reparation and guarantees of non-repetition.

Not allowing violence to re-emerge and continue to affect the same people and communities time and again is, and will continue to be, fundamental. Recognizing that the state has failed to protect human rights defenders and must move towards a collective and preventative protection response is, and will continue to be, fundamental. Protecting the rights of women and children who have experienced violence in their lives time and again is, and will continue to be, fundamental.

The new government, local authorities, state institutions and Colombian society must commit to changing a history of bloodshed and dispossession. They cannot continue to fail Indigenous and Afro-descendent communities that have historically been forgotten and abandoned by the state. Now is the time to act.

The new government, local authorities, state institutions and Colombian society must commit to changing a history of bloodshed and dispossession. They cannot continue to fail Indigenous and Afro-descendent communities that have historically been forgotten and abandoned by the state. Now is the time to act

Erika Guevara Rosas, Americas Director at Amnesty International

This article was originally published in Spanish by El Espectador