Bryan Andy, member of Amnesty Australia’s Indigenous Peoples Rights Team, shares the experience of the human rights education workshop for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples, that took place in Palm Island in June 2012.

Bryan Andy, member of Amnesty Australia’s Indigenous Peoples Rights Team, shares the experience of the human rights education workshop for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples, that took place in Palm Island in June 2012.

EMILIE: Hi, this is Emilie White with the Human Rights Education Network news connected online with bryan Andy, who works on human rights education in Amnesty Australia’s Indigenous Peoples Rights Team.

BRYAN: Hi. I’m a Yorta Yorta man from Australia. I work in Melbourne with Amnesty Australia. We have offices all over the country, but I’m based in the Melbourne, Victoria Action Centre, in the South-East of our country and I’m the Human Rights Education Coordinator for Amnesty within Australia. Specifically I work with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander People, or indigenous people as we prefer to call them across Amnesty.

EMILIE: You just sent me a report on Amnesty’s first-ever unaccompanied venture delivering an empowering human rights education workshop for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples. The report is really inspiring. Can you share with us how the event came about and how it went?

BRYAN: The event came about through Amnesty Australia making a commitment to human rights education by employing somebody in my particular role to deal with and to work alongside Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Communities.

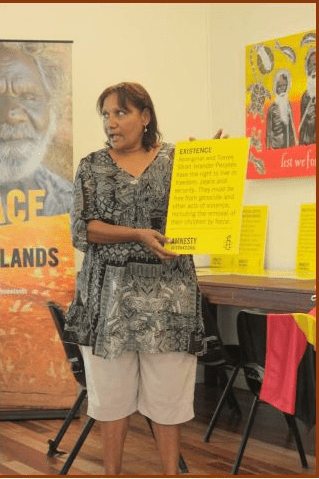

As part of our campaigning and rights activism work across the country, people within the Indigenous Peoples’ Rights team have made links with people from Palm Island. Palm Island is a small island off the Queensland coast, the North coast of Australia. It’s near a place called Townsville and it’s got a pretty interesting history where there’s heaps of rights violations that have occurred, whether you’re talking today, nowadays, as to rights violations that have happened, and historically they’ve had a really awful history.

People from the Indigenous Rights Team connected with these people and said we would like to do an empowerment training with you and from that interaction and teamed up with my employment we were able to do a workshop with people from Palm Island to empower them to better understand human rights and also tools like working with the media, how to campaign effectively and how to make change using a human rights based approach within their community. So give them some kind of sense of self-determination.

EMILIE: Who was part of the workshop, how did you choose them and was it difficult to get people to turn up to the workshop?

BRYAN: Yes, it takes a long time, it’s a long process. I visited Palm Island about three times before presenting the workshop so it took a lot of initial engagement, planning and consultation with the communities. I guess one of the ways we work as the Indigenous People’s Rights team is to go through a process of free prior and informed consent based on the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous People. We want to walk the walk, when we talk the talk. And so we go through a lot of planning and consultation within the communities that we work with, and that was the same case with Palm Island.

I went up there three times and also with other members of the Indigenous People’s Rights team to sit down with community members and their leaders to talk about what they might want from the training and who might be involved. We talked about things like how to promote it, how get word out there, how to engage people. It’s basically a long process of sitting down with people and saying, what do you want? What would we want from Amnesty’s perspective, how can we work together for the best outcome for the communities?

So that’s the kind of process we go through. It seems long-winded but it is necessary and part of the process. Just to give you an indication I said I was based in Melbourne and Palm Island is probably about two thousand kilometres North of Melbourne, so when I say three trips prior it’s a lot of time and a lot of travel, but it’s not without its rewards.

EMILIE: The workshop report mentions that the workshop provided Amnesty with an engaged and trusted avenue to continue working in partnership with the Peoples of Palm Island to alleviate human rights concerns. That sounds really fantastic. What do you mean exactly by that and how do you think that was achieved?

BRYAN: Amnesty’s work with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander People is fairly new. We’ve had Uncle Rodney Dillon, who’s a Palawa from Tasmania, work with Amnesty for six years. So realistically our work with indigenous peoples is fairly new, it’s in its infancy. So my role within human rights education is about empowerment but it’s also about engagement and consulting with communities to bring them on board.

You know while we are a global movement there aren’t great numbers of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander People involved in what we do. So I want to be able to engage them in that manner, but also I just want to bring people up to speed on what are human rights.

There’s a sense of what rights are across the country within Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australia, but we really need to illuminate what human rights can do and how they can be utilized for effective advocacy and campaigning, so that’s the intention. It’s about engaging initially and then talking the same language, being on the same page. That was a big aim of our workshop and a lot of the work that we do across the country.

As part of the workshop with the human rights education workshop on Palm Island, what we did was, people wanted to work on issues like how to incorporate local culture into their education, which is a human right, basically about the right to practice your culture and incorporate that into a non-indigenous education system, so people worked on activities like that, that allowed them to go through the steps. So, if they want to make change within their education system, these are the steps you might want to do in order to create that change. So it’s about empowering them, simple things that they wanted to do, not simple but, processes that they wanted to go through as a community to make change and establish human rights.

EMILIE: At the end of the workshop you conducted an evaluation with the participants, what did they think of the meeting?

BRYAN: People overwhelmingly thought it was valuable, they were very grateful for what we had done and the evaluation process is something that we do just to make sure that we are on track. We do it in two ways. We have a form that we allow people to fill out and to respond to in a private manner but we also conduct conversations around the evaluation as part of the workshop to close it off. And that’s because we are often working with people with low literacy levels, they don’t necessarily read or write. So we have got to incorporate ways to ensure that we capture their feelings and feedback, and that’s just one of the processes that we do.

The evaluation talks about whether they thought the workshop was valuable or not, what the content was like for them, how they might want to utilise that content and the learnings from the workshop and we also asked a kind of contribution.

For example we did a workshop in Perth recently and we have a section on media that we like to present to promote peoples’ engagement with the media in a positive way. One of the things that came out of that was the question: “How do we use social media, we’d like to learn more about social media as a platform to work within the media.” And we were like: “hey, that’s a great idea!” So the evaluation while it gives us some feedback and some understanding of how we’re tracking we also utilise it as a way to get further feedback and also further insight into how we can strengthen our work.

EMILIE: What happens now in Australia following from this workshop and in general for your HRE work for this year?

BRYAN: This year we are developing a justice campaign that will look at the criminal justice system and how that is badly affecting young indigenous people across the country. We’ll focus on Western Australia, Northern Territory and Queensland as sites where the statistics are worse, and part of my HRE work will be very much around that engagement and consultation with the community, so what we will do is we’ll run two HRE based workshops in each of those three States.

We view these as a way to bring people in, so they understand what we’re up to from Amnesty’s perspective but also we want them to be able to talk the same language that we do, so if we both see a violation whether it’s from Amnesty’s or the community’s prospective, we want to empower people to talk that talk as we gear up to do our report on the criminal justice system.

Also we are going to develop a campaign that will then hopefully engage a lot of the people that are involved with that training, rights-holders as we call them, to speak to the media, to join the campaign, to help us to develop things, to be there alongside us.

We are trying to make a strong link between HRE and campaigning. There can be a bit of a perceived split within those two streams within Amnesty and I guess it’s about really wanting to focus on making sure that HRE is an integrated part of campaigning, because like I said earlier, we are working with new people, we’re working with people that we haven’t worked with from an Amnesty perspective, so we really need to bring those two worlds together, those two streams together, to have the best outcome for all.

EMILIE: That sound s excellent and I look forward to our next update with you to hear more about how that goes. In the meantime thank you very much for your time and thanks for engaging with the network and letting us all know what’s going on in Australia.

Interview conducted by Emilie White, HRE Network & Communications Coordinator in the IS HRE team on 6 February 2013, online, for the International HRE Network News.