Kenya has a critical mass of budding and young tech-savvy activists who use their online presence for civic engagement. Recently, activists critical of the Kenyan government have been met with aggressive, sometimes vicious, attacks. Abdullahi had a chat with Edwin Kiama, one such activist, whose experience is a demonstration of a much bigger problem – attacks on critical voices online.

On the balmy June afternoon when we met at my office located west of Nairobi, his phone beeped endlessly. If it wasn’t a status update on his Facebook page, it was a WhatsApp message, or a phone call. To keep his phone battery going, he hooked it up to a portable power bank.

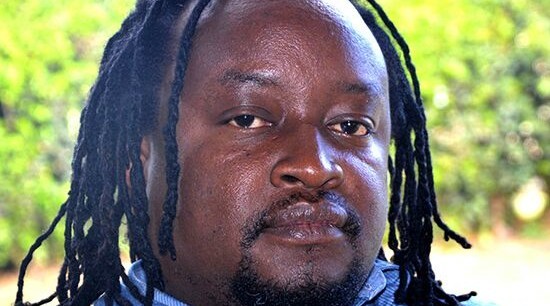

Meet Edwin Kiama, a social justice activist who organizes online with the help of almost 50,000 followers of his Twitter handle, @WanjikuRevolt.

A cursory scroll through Edwin’s Twitter timeline provides a glimpse into contemporary online conversations in the country. If he’s not tweeting about the negative environmental impact of the proposed Lamu coal plant, he is tweeting about the ruling Jubilee Party’s manifesto, or the Independent Electoral and Boundaries Commission (IEBC)’s failure to publish the voter register.

Edwin is as active on Facebook as he is on Twitter. His Facebook page has almost 40,000 followers. To make his accounts and timelines dciverse and representative, Edwin says he adds people who are not necessarily from his ethnic group. In a country polarised along political and ethnic lines, this is a testament to his cross-ethnic appeal.

The attacks

Edwin’s online activism was motivated by his desire to provide a counter-narrative to the incumbent political party’s views. Because of his online advocacy, Edwin has attracted the wrath of many supporters of the Jubilee Party’s administration. The fact that he hails from the President’s ethnic group (Gikuyu) makes him an easy target. He is seen as a sell-out. In most cases, individuals vote or support a particular politician or a political party based on ethnicity.

The attacks directed at him range from mild to abrasive.

Some people initially start by getting embedded on my timelines, support most of my viewpoints, but suddenly switch sides and start attacking me.

Edwin Kiama

He recounts being in a pub in Kinoo, on the outskirts of Nairobi, when someone came up to him and shouted ‘Githongo’. This was in reference to the former anti-corruption whistle-blower, John Githongo, whom Edwin used to work with at Inuka Kenya Inc- a grassroots social movement. Githongo is on record for whistle-blowing on one of the biggest corruption scandals in Kenya, Anglo Leasing, in which some powerful former government officials were named. Fortunately, the confrontation did not become physical.

Online, he is constantly under attack. Edwin says, “Some people initially start by getting embedded on my timelines, support most of my viewpoints, but suddenly switch sides and start attacking me.”

He says such attacks are the “most difficult to detect and defend against”.

But, he says, he remains unfazed. This is in part because he is aware of his gender privilege. Attacks against female online activists tend to be disproportionately vile and personal.

Edwin says he meticulously plans all his social media engagements. Prior to embarking on any online campaign, Edwin and a small team of trusted confidants discuss the ideas on a WhatsApp group. During the planning, they anticipate the lines of attacks and the required responses. This creates an online community to come to his defence in case of attacks.

But the Kenyan government, an early adopter of online engagement, also uses the internet to bypass the mainstream media to reach its supporters. The Jubilee Party’s administration branded itself as a ‘digital’ administration, in contrast with the political opposition, labelled as ‘analogue.’

Activists like Edwin are thus up against an equally tech-savvy administration with far greater resources to undermine their efforts. But Edwin believes the people, united, are stronger than any government. He uses the term ‘Wanjiku,’ a Kenyan metaphor for the common (wo) man, for this reason.

As Kenya’s general elections approaches, the Communications Authority of Kenya's less than reassuring statements about shutting down the internet in the event of electoral violence could well mean that voices like Edwin’s could be shut down at a time when critical citizen voices are most needed.

Abdullahi Halakhe

As Kenya’s general elections approaches, the Communications Authority of Kenya has issued less than reassuring statements about shutting down the internet in the event of electoral violence. This means voices like Edwin’s could be shut down as well, at a time when critical citizen voices are most needed.

Edwin and other critical citizen voices are pushing for change one Facebook post and a 140 – character tweet at a time.