The six countries that make up the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) – Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates (UAE), Bahrain, Kuwait, Oman and Qatar – host the majority of the estimated 23 million migrant workers living in the Arab states.

These are some of the richest countries in the world. Sadly, they have also become notorious for the systematic abuse and exploitation of the migrant workers who contribute so much to their economies. Unpaid wages, forced labour, dangerous working conditions and unsanitary accommodation facilities are too often part and parcel of the migration experience.

All GCC states operate versions of the ‘kafala’ sponsorship system, which ties the workers’ legal right to be in the country to their contracts. This means people risk being imprisoned or deported if they leave their jobs without the permission of their employers. In Saudi Arabia migrant workers cannot even leave the country without such permission.

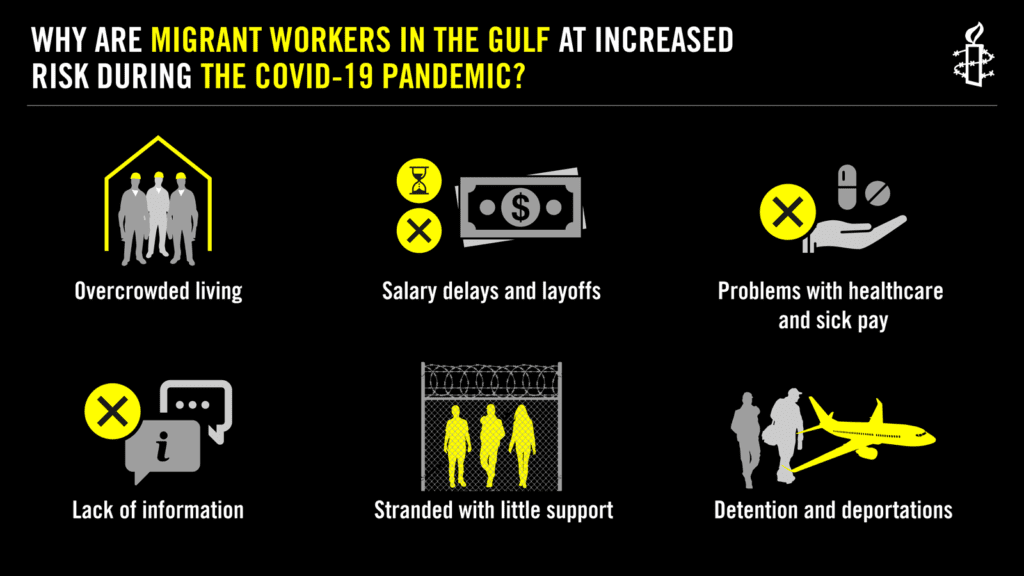

The spread of COVID-19 has put migrant workers at even greater risk. Along with other organisations, Amnesty International has already raised its concerns about the impact of the pandemic on protection of migrant workers in the Gulf, where common issues like overcrowded accommodation now present a public health risk.

An action plan for change

But this crisis could also be an opportunity for change. Throughout the Gulf, COVID-19 is shining a spotlight on the unsanitary, overcrowded conditions many migrant workers live in, and their precarious legal status.

Suddenly, the consequences of denying people their basic rights are impossible to ignore.

By taking the right actions to protect migrant workers now, governments and businesses in the GCC could start to turn the tide on years of abuse. Gulf countries must start to treat migrant workers equally and eliminate all systems that discriminate against them and infringe on their human rights.

Here are 7 things governments and employers need to do so that every migrant worker in the Gulf has the right to healthcare, adequate housing, social security and just working conditions.

1. Ensure migrant workers have adequate living conditions

The majority of migrant workers in the Gulf countries are low-paid labourers and they are often accommodated in dormitory-style “labour camps”.

Generally speaking, they are provided small rooms as accommodation which are typically shared between six and 12 people who sleep in bunkbeds. Workers tend to share communal bathrooms and kitchens which are often unsanitary and inadequate, sometimes even lacking electricity and running water.

No one should ever be living in these conditions, but the spread of COVID-19 has highlighted the severity of the situation and the need to urgently rectify it. Following hygiene guidelines and adhering to social distancing measures are all but impossible in these circumstances.

Acknowledging the magnitude of this issue, some governments have taken steps to try to limit overcrowding. For example, the Bahrain government urged employers to ensure that no more than five workers are housed in a room and that each worker should be three meters away from the other. In Kuwait, some workers were reportedly evacuated from their labour camps to alternative accommodation.

In Qatar, the government introduced new health and safety guidelines to protect workers in labour accommodation and on construction sites, and in coordination with companies are trying to implement stricter hygiene standards.

Lack of transparency and access to most of the Gulf countries makes it difficult to assess the success and implementation of such measures across the region, and it is unclear whether companies are fully complying with them.

To do:

- Gulf governments and companies should work together to identify overcrowded and unsanitary labour accommodations.

- They should temporarily relocate concerned migrant workers to facilities where they can practice social distancing, maintain the necessary hygiene standards like regular washing of hands and other measures required to protect themselves from infection.

- Companies should implement health and safety recommendations in accommodation and workplaces and Gulf governments should ensure that companies enforce these measures.

- Gulf governments should ensure that migrant workers have equal access to testing for COVID-19 and those with symptoms are provided with facilities to self-isolate and access health care.

- Gulf governments should coordinate with relevant embassies so that all migrant workers have enough food and water and adequate sanitation.

Moving forward, no migrant worker should be made to live in squalid, overcrowded accommodation: Gulf governments and companies should ensure adequate living standards for all migrant workers.

2. Make sure everyone is fairly paid

Prior to the outbreak of COVID-19, non-payment and late payment of wages was a common complaint of migrant workers in the GCC. Most migrant workers in GCC countries come from countries like India, Nepal, Bangladesh, Kenya and the Philippines, and work in low-paid jobs in construction, hospitality and domestic work. Many people have to take out loans to migrate, which can trap them for several years in cycles of debt and exploitation.

Now, as across much of the world, businesses in GCC countries are facing extraordinary challenges to their operations as a result of the pandemic. Migrant workers, because of their precarious work situations, are likely to be hit hardest by this situation.

Some GCC governments have announced measures to mitigate financial risks for some workers.

For example, the Qatar government has offered loans to businesses to ensure that workers living in quarantine, isolation or areas under ‘lockdown’ will continue to be paid.

Other countries such as Saudi Arabia and Bahrain also promised to financially support businesses to pay salaries, however their schemes appear designed to only support their own nationals.

None of the schemes in place across the GCC fully extend to protect the salaries of migrant workers in all circumstances.

Some governments such as Saudi Arabia, Qatar and UAE have told employers that they can ‘mutually agree’ with their employees for them to take unpaid leave, or use their annual leave during this period, in an effort to preserve jobs in the long run. However, given the power dynamics at play in these countries, where the kafala system means employers hold great sway over workers, it will be very difficult for workers to effectively negotiate with their companies in this regard.

As a result, hundreds of thousands of migrant workers risk being left at the mercy of their employers who may summarily stop paying wages, force them to take unpaid leave or simply dismiss them from their jobs.

At the best of times migrant workers in many GCC countries face immense challenges in securing justice for labour abuse and exploitation. Cases of unpaid wages and struggles to get remedy in courts have been frequently reported in Qatar, Bahrain, UAE and others.

Today, with access to labour courts across the GCC restricted due to the pandemic, it will be virtually impossible for workers to claim their rights and recover unpaid wages.

To do:

- Employers and workers should mutually agree and explore all possible work arrangements with a view to ensuring that workers’ jobs and salaries are protected during the lockdown period.

- Gulf governments must step in to ensure that they bridge any gaps with financial support to workers. This support should be grounded in equality and in line with the support provided to their nationals. At a minimum, Gulf governments must ensure that workers’ right to an adequate standard of living is protected.

Moving forward, Gulf governments and employers should ensure that migrant workers are always paid on time and in full. Governments should hold to account any employers that fail to do so.

3. Ensure people get health care and sick pay

One consequence of the kafala system, and the power imbalance it creates, is that migrant workers may feel forced to work when sick for fear of losing their pay or even their job. During this pandemic, more people may have to make the impossible choice between their health and their pay.

What’s more, with many migrant workers in the Gulf now facing government-imposed restrictions on movement, it’s hard for them to access the recommended preventive care, goods and services so crucial to their protection unless provided by governments and companies, especially in cases when they are not allowed to leave their accommodations.

Governments in the Gulf have tried to introduce some measures to alleviate such risks. For instance, Qatar and Saudi Arabia are both offering free health care services to all migrant workers irrespective of their legal status in the country. However, it is unclear to what extent these measures are being implemented and if migrant workers in Gulf countries are receiving treatment without any discrimination or retaliation.

To do:

- Gulf governments and employers should work together to enable and assure all migrant workers, including those who are undocumented, receive affordable health care without any discrimination or fear of reprisal. The inability to pay must not be a barrier to accessing health care.

- Employers should give sick pay to workers who are unwell or who need to self-isolate and should not dismiss them from them their jobs for having symptoms of COVID-19 or contracting the infection.

Moving forward, Gulf governments and employers should ensure that migrant workers have access to the full range of social protection, including sick pay, financial support and affordable health care without any discrimination.

4. Ensure access to information

It’s essential that people have access to timely and accurate information about COVID-19, including what they can do to protect themselves. But for migrant workers across the Gulf, such information may not always be easily accessible.

A major problem is that most of these workers do not speak Arabic, the official language in all GCC countries. They are therefore reliant on governments providing detailed information in their own languages on measures such as social distancing, or recommended hygiene routines.

Qatar for instance launched a series of social media campaigns addressed to migrant workers and employers and has set up a hotline to support migrant workers.

Without full information, migrant workers are also at heightened risk of unwittingly breaking the law and risk being penalised for it.

Access to information may be a particular problem for domestic workers, who are isolated in homes and often don’t have mobile phones.

To do:

- Gulf governments should work with employers and relevant embassies to provide migrant workers with information on COVID-19, in languages they can easily understand. This should include information on symptoms, groups considered to be at high risk, protective measures, restrictive measures imposed to contain the spread, and how to access health care.

Moving forward, both governments and employers should put a system in place where migrant workers have access to accurate information in languages they understand about their rights regarding working and living conditions, social protection and access to healthcare, as well as laws and regulations.

5. Provide for workers who are stranded in the country

One of the first measures introduced by Gulf countries was a gradual ban on many flights, including those coming from major labour sending countries, such as India, Nepal and the Philippines. Many of the sending countries also halted incoming flights including from Gulf countries.

Such travel restrictions mean many migrant workers now find themselves stranded in the Gulf, having either finished their contracts or been dismissed from their jobs. Those who have been required to take unpaid leave due to COVID-19 and would rather return home than remain in the Gulf without an income, are unable to.

In addition to being stranded far from their families and struggling to get by, this situation also opens some migrant workers up to being penalised for failing to comply with immigration requirements.

Most Gulf countries such as Bahrain, Kuwait, and UAE have introduced amnesties for irregular migrant workers or extended permit deadlines to avoid rendering migrant workers in irregular status in the countries during this pandemic. But hundreds of migrant workers remain stranded in these countries without any means to support themselves.

To do:

- Gulf governments should provide amnesties or extend visas for those who are not able to comply with immigration conditions due to restrictions imposed as a result of this pandemic.

- Gulf governments should ensure that stranded migrant workers also have access to adequate accommodation, food, health care and financial support while they wait for the travel restrictions to be lifted.

- Embassies of sending countries should account for their nationals who are in such situations and work with Gulf governments to ensure that their right to health and adequate standard of living is upheld.

6. Detention centres and deportation

“The jail was full of people…. All the people were fed in a group, with food lying on plastic on the floor. Some were not able to snatch the food because of the crowd.”

This is how one Nepali man described the time he spent in detention after being arbitrarily arrested by the Qatari authorities in March. Amnesty International documented how hundreds of migrant workers were rounded up and detained by police in parts of Doha. Police told them they were being taken to be tested for COVID-19 and would be brought back to their accommodation later. Instead they were crammed on to buses and taken to a crowded detention facility where many were held for days.

Saudi Arabia has also reportedly detained hundreds of Ethiopian irregular migrant workers and sent then back home.

Migrant workers in the Gulf could be detained for overstaying their residence permits, often because their sponsors failed to renew it or because they fled abuse and exploitation.

Deportation centres and detention facilities in Gulf countries are notoriously overcrowded and lack adequate water and sanitation which increases vulnerability to infection.

There is a risk that the pandemic will result in more migrant workers being sent to these centres, if they break quarantine rules for example, or if they are stranded in the country without a valid visa.

To do

- Gulf Governments should ensure that no one is detained solely for breaking quarantine rules, and immediately release all those detained under these circumstances.

- Gulf governments should announce grace periods for migrant workers unable to comply with immigration requirements due to travel and other restrictions and refrain from penalising them during the COVID-19 crisis.

- Gulf governments should refrain from expelling undocumented migrant workers without due process.

- Gulf governments should ensure that everybody in detention centres, including migrant workers, are provided with necessary facilities to practice social distancing and protect themselves from risks of infections. Embassies of migrant workers’ sending countries should work with these governments to support their nationals in detention.

7. Don’t forget domestic workers

Amnesty International is especially concerned about domestic workers, who are among the most vulnerable group of migrant workers in the Gulf. Often isolated within homes and highly dependent on their employers in almost every aspect of their lives, they are also not covered by labour law protections across the Gulf.

With many schools closed and entire households restricted from leaving homes, the already-excessive work load of many domestic workers is likely to increase. They may be expected to help look after children in addition to their usual work. With the start of Ramadan in April, domestic workers will probably have to work even harder as their workload usually increases during this month further extending their long working hours.

Many domestic workers in the Gulf have no day off at all. For those that do usually get a day off per week, government-imposed restrictions to slow the spread of COVID-19 will further curtail these already limited freedoms, in some cases limiting their ability to reach out to their networks or embassies to seek any support that they might need.

To do:

- Gulf governments should issue guidance to employers of domestic workers clearly articulating limits on working hours, the need for a weekly day off, daily rest and the provision of protective equipment where necessary.

- If they fall ill, domestic workers should have access to affordable and adequate health care facilities to self-isolate, rest, and the possibility to take paid sick leave. All their rights to just and favourable conditions of work must be protected.

Moving forward, Gulf governments and employers should work together to protect domestic workers from violence, abuse and discrimination. They should include them in labour laws in order to guarantee their labour rights which include limited working hours, day off, overtime pay and freedom of movement.